(Bloomberg) -- Boris Johnson’s government wants to return the British economy to growth rates it enjoyed before the financial crisis. Mark Carney isn’t convinced that’s realistic.

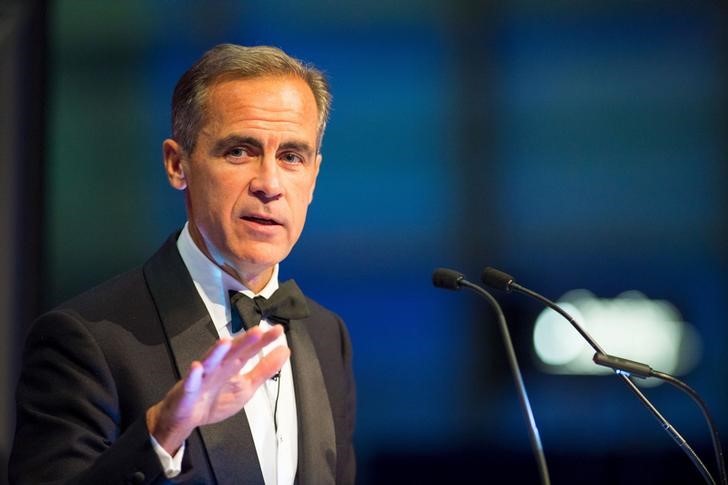

On the eve of Britain’s departure from the European Union, the Bank of England governor delivered a downbeat assessment on Thursday of the medium-term outlook, with growth predicted to be less than 1% this year -- the worst performance in a decade.

That’s barely a third of the pace sought by Chancellor of the Exchequer Sajid Javid. The problem, according to Carney, is that Britain outside the EU will continue to be hamstrung by the abysmal productivity growth that has bedeviled the economy for years.

The central bank’s final assessment of the economy before Javid delivers his budget in March -- when Carney also leaves office -- saw the biggest downgrade to the BOE’s outlook since the aftermath of the 2016 Brexit referendum. Officials predict growth will remain below 2% in 2021 and 2022, even if they cut interest rates and Johnson manages to strike a quick “deep” free-trade deal with the EU this year. The central bank hasn’t taken the government’s spending plans into account.

The predictions will inevitably expose Carney to accusations -- once again -- that he’s anti-Brexit and talking down the economy, though the BOE’s cautious outlook is widely shared. The median estimate of 59 economists surveyed by Bloomberg is for growth of 1.1% this year, with only Nomura predicting more than 2%.

“Growth is too low,” Javid said at the World Economic Forum in Davos this month. “We need to get up to U.S. levels of growth. It’s much easier said than done, but because of the political and economic stability we have, the policies we have, I think that can be done.”

The U.S. is forecast to expand close to 2% this year and next.

Crucially, the BOE lowered its estimated speed limit, the rate it thinks the economy can grow without generating inflation, to around just 1%.

Its pessimism is partly explained by productivity, which has “persistently disappointed” with growth of just 0.3% a year over the past decade. While Britain is far from alone -- productivity has been slowing across advanced economies -- it nonetheless stands out. Only Italy has posted a worse performance among Group of Seven nations. The malaise has led to years of wage stagnation that is only now coming to an end.

Britain has instead relied on a plentiful supply of labor to drive the economy. But with employment at a record high, there is now limited scope to bring in more workers, and post-Brexit immigration curbs could intensify the squeeze. Faster growth therefore depends on getting more from existing employees.

What Our Economists Say:

“The bank’s downgrade to its potential growth forecast is a timely reminder of the productivity challenge that was facing the U.K. long before the 2016 referendum. With the labor market at full capacity and migration set to be curbed, even achieving growth of 2% would require productivity growth well in excess of the meager levels seen over the past decade.”

Dan Hanson, Bloomberg Economics

Javid -- like his predecessors -- has made boosting productivity a priority. His March 11 budget is expected to include investment in training and billions of extra pounds for infrastructure, particularly in under-performing parts of northern and central England, where pro-Brexit voters backed the ruling the Conservatives for the first time.

The weakness of productivity growth, which averaged over 2% before the crisis, hides deep and persistent disparities between regions. London and southeast England significantly outperform other parts of the country, with the gap no narrower than it was in 2008.

Johnson has spoken of his ambition to “level up” across the U.K., and the budget is expected to deliver a fiscal stimulus equal to more than 1% of economic output. But Carney said any payback may not be seen for years.

“Large structural changes need to be made in order to get the rate of supply growth up,” he said. “The chancellor would recognize that this is not something you can change overnight.”

Signs of a post-election bounce, plus the prospect of an expansionary budget, were sufficient for the BOE to keep interest rates on hold this month, but Carney made clear that policy makers stand ready to cut if necessary. Trade talks with the EU pose major risk. If negotiators fail to reach a deal, Britain will again be facing an economically disruptive break with the EU once transitional arrangements end on Dec. 31.

Criticism of Carney among pro-Brexit advocates centers around his pre-referendum comment that the consequences of a vote to leave the EU “could possibly include a technical recession” -- something he stressed at the time was not actually in BOE forecasts. In the event, the economy continued to expand.