(Bloomberg) -- A month after Hurricane Maria battered this mountainous stretch of central Puerto Rico, recovery remained elusive along Highway 152, where 82-year-old Carmen Diaz Lopez lives alone in a home that’s one landslide away from plummeting into the muddy creek below.

Without electricity, and without family members to care for her, she’s become dependent on the companionship of a few neighbors who stop by periodically. But a collapsed bridge has made it challenging to even communicate with her friend across the creek, so she’s lived for the most part in solitude, passing the electricity-less days singing “Ave Maria” and classic Los Panchos songs to herself, lighting candles each night so she can find the bathroom.

“I just ask the Lord to take care of me, because he’s the only one I have,” Diaz Lopez said Wednesday.

Diaz Lopez and her neighbors along Kilometer 5 of this badly hit mountain road in Barranquitas municipality are among the hundreds of thousands of Puerto Ricans still at risk as the recovery effort heads into its fifth week. Pipe water returned here in a trickle a few days ago, and the collapsed earth that blocked the road and sent muck into homes has been half-way cleared. But a phone signal is still non-existent, and residents are far from any semblance of sustainable self-sufficiency.

The situation threatens to undermine the economic and fiscal future of the island, and is already fueling a flood of Puerto Ricans leaving for the mainland. At this stage in the recovery from the Category 4 storm, many find the current state of the U.S. commonwealth -- home to some 3.4 million American citizens -- unthinkable.

“I just haven’t seen a situation where people don’t have access to basic services for so long,” said Martha Thompson, the Puerto Rico response coordinator for the Boston-based charity Oxfam Americas who also worked on the response to Hurricane Katrina.

Meeting at the White House with the commonwealth’s governor, Ricardo Rossello, President Donald Trump said Thursday that his administration’s response to Maria deserves a perfect “10” rating. He also drew attention to the fiscal mess in Puerto Rico that predated the hurricane, suggesting he wants repayment of any reconstruction loans to take precedence over the island’s existing $74 billion debt that pushed it into bankruptcy.

For a QuickTake on the island’s economic and fiscal situation, click here.

Only tenuous, provisional measures seem to be preventing a much greater humanitarian crisis in Puerto Rico. A government task force has restored electricity to many hospitals and healthcare facilities, but others are sustained by diesel generators that occasionally fail. (APR Energy Chairman John Campion, whose company rents the units for natural disasters, said in an interview that such generators typically have a life span of 500 hours, and the crisis has already lasted longer than that.)

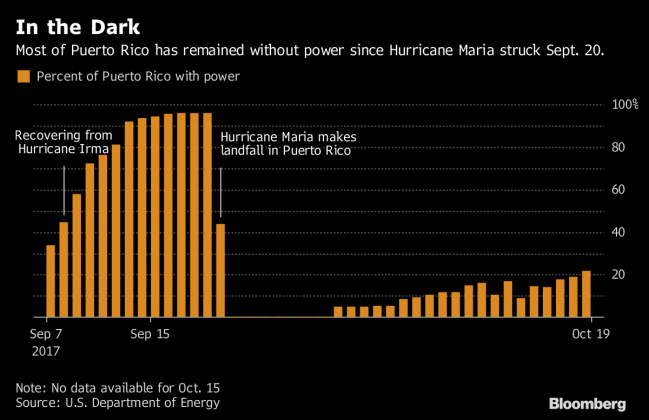

About 83 percent of residents and businesses -- not just in the rural mountains, but across the island -- are still without electricity.

As of Friday, one-in-three residents lacked running water, and only about half of cellular towers were operational. Meanwhile, the official death toll, currently at 49, keeps creeping higher, with 76 islanders still reported missing.

Many blame an insufficiently robust federal response, while authorities note the myriad logistical challenges that make the high-poverty island distinct from storm-battered states such as Florida or Texas.

Certainly, there have been improvements. In the days after the storm, the entire island appeared engulfed in pandemonium; the airport operated at a fraction of its normal capacity with leaky ceilings, no air conditioning or escalators; frantic islanders formed half-mile long lines for gas and diesel; and mayhem ensued on roads and highways, even in the capital, as people tried to dodge fallen trees and street lights.

This week, by contrast, the airport was back in operation, with a blast of cool air greeting new arrivals at the end of the jet bridge and slot machines in the terminals blinking and jingling. The roads around the capital have been largely cleared, as have many major highways.

But the reality remained very different in the mountains of central Puerto Rico. Back in Barranquitas, Erika Perez, 43, wondered how she would sustain her family. She lives just up the hill from Diaz Lopez with her husband, son and daughter, ages 52, 13 and 14, respectively. They have dogs, pigs and chickens, which supplied the eggs that kept the family fed during the early days after the storm, when the mudslides had completely boxed them in.

Perez said they’d been basically cut off for some 10 days, and she had worried about what would happen if her daughter’s asthma got bad.

Asked if she felt forgotten by the authorities, she gestured to a heap of trash that had been accumulating since even before the storm, insects circling. “We don’t ask for much, but at least give me that,” she said. “Help us out for sanitary purposes.”

Her husband had invested much of his time and money in plantain fields up the road, but the storm had obliterated much of the crop, and what was left had been stolen by those desperate for food. The family also ran a bar next door -- frequented by Diaz Lopez, who said she went for the live music -- but the prospects looked grim there, too, with no cars passing through the area.

The Puerto Rican economy was in a dire situation before the storm, and now it’s been reduced to a shadow of even that former self. Small business owners everywhere have been forced to trade their digital inventory systems and credit-card machines for old-fashioned paper and cash, and they’ve been grappling with how to keep tabs on employees.

“Everyone is in survival mode," said Gustavo Velez, an economist who runs the Inteligencia Economica consulting firm in San Juan. "There’s no work, no earnings. People are buying what they need for the day."

He said the situation will only snowball, fueling a massive exodus to the mainland, if the government can’t come up with resources and a viable plan. Governor Rossello has warned that millions could leave.

As for Diaz Lopez, she said she’ll keep looking after herself. She’s found a new apartment connected to an auto body shop up the hill and out of the path of mudslides; she’s just waiting for the owner to clear the space out so she can move in at a cost of $250 a month.

She was left alone on the island when her ex-husband died, her son was killed by a drug overdose and the last of her extended family moved to the mainland. She wondered why the authorities, local or federal, hadn’t done more for her. In the meantime, she said she knew how to do enough to stay healthy and safe during the long, dark nights.

“You’d think they’d say, ‘Here’s a woman on her own, an elderly woman, let’s go help her’,” she said, standing in the doorway of her home with her dog. “But I’ll be okay. I take life as it comes.”

(Updates death toll, number of missing in 10th paragraph.)