Also, in contrast to the positive U.S. economic momentum observed before the virus hit (2.1% q/q saar in 2019 Q4), the Canadian economy was in quasi-stagnation before both the rail disruption and the virus started to rattle several industries. Indeed, real GDP stalled (+0.3% q/q annualized) during the last quarter of 2019, according to Statistics Canada’s report released this morning. Also, we estimate that the Canadian economy could stagnate again during the first quarter of 2020. This is based on new information collected since we published a preliminary note earlier this week on the coronavirus and rail disruption economic impacts. We also expect a freeze in hiring and temporary job losses for at least two months (our call for next week’s LFS at 0K m/m for February) and lower oil prices to bring down total CPI inflation below 1.5% by April.

This unusual situation requires a very pragmatic approach for the Bank of Canada. It is not clear that a policy rate cut on March 4th is the most appropriate medicine at the moment. An isolated 25bps insurance cut of the overnight rate target or even a 100bps reduction will not dissipate the pre-emptive measures weighing down on demand of services and the growing number of temporary layoffs. Another argument in favour of a pause on Wednesday is that the cost of waiting six weeks at the April 15 monetary policy meeting is low.

Also, if the BoC eases on its own while central banks like the Federal Reserve are not ready to act, it may just fuel FX volatility. If the outlook becomes gloomier due to a crunch in credit conditions and second-order effects in the real economy and labour market conditions, then rate cuts would be required. Furthermore, if the BoC eventually cuts its policy rate, it could be part of a coordinated effort on any given business day, similar to the global easing announced at 7AM on October 8th 2008 during the financial crisis.

Altogether, does the BoC feel the downward revision to the outlook relative to the January MPR forecast is already enough to justify rate cuts?

If the BoC’s baseline coronavirus scenario is similar to what the EIU proposes, then the answer is no in our view. But our call hangs out by a thread because BoC officials have been already discussing the possibility of a rate cut at the previous three meetings. In other words, the virus spread arrived when the BoC was not comfortably sitting on the 1.75% policy rate. Granted, the 0.3% m/m increase in real GDP by industry for the month of December is a healthy figure although we estimate that 0.1ppt is attributed to the rebound following the CN strike that ended in late November. At the same time, the soft spots in the Canadian GDP quarterly report, including a reduction in business investment in M&E (-3.6% q/q annualized), another decline in exports (-1.3% q/q annualized) and weak consumer spending (+0.5% q/q annualized) could be enough to bring a majority of BoC officials to opt for a rate cut, regardless of the coronavirus economic impact.

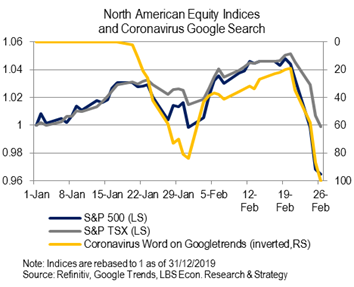

Coronavirus fears have led to a stock market correction (see chart). The U.S. 10-year bond yield sits at an all-time low as the COVID-19 poses a major downside risk to the outlook. We do not have a firm view on the precise impact related to the virus. At this stage, we know enough about the broad picture to say that our 2020 original base-case scenario of a marginal improvement in global economic momentum and corporate earnings definitively won’t happen, regardless of the timing and magnitude of the rebound once the virus is contained.

The highly-integrated global supply chain is disrupted, commodity prices are in free fall and precautionary measures weigh down on services-related industries, such as travel and leisure. The mix of supply and demand economic shocks makes it very challenging to strip the noise and get a real signal. Economically vulnerable parts of Europe, the Middle East and Asia are likely in contraction mode already and heightened financial stress could be next. In the U.S., the CDC states that more virus cases are likely raising the spectre of more pre-emptive measures and disruptions in North America within the next month. The good news is that Germany mulls fiscal stimulus, while China, Taiwan and South Korea already announced proactive macro policies.

As a guideline to what could happen, multiple scenarios revealed earlier this week by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) are useful. The base-case scenario assumes that the virus will be under control by the end of March. The slowdown in the number of new cases reported by China over the last few days reinforces this base-case scenario pegged with a 50% probability of occurrence. Under this scenario, real GDP growth in China would slow moderately from 6.1% to 5.4% because of the residual supply disruption in industrial activity and the net loss of services activities that will not be recouped. Thus, in the EIU base-case scenario, global economic growth remains at last year’s weak mark of 2.9%. So far, the cooling demand in some services sectors, such as travel and tourism reflects a cautious behaviour tied to growing concerns rather than a full-blown deterioration in labour market and credit conditions. However, the risk of a fundamental and long lasting negative shock will increase if a large number of companies face lower revenues and higher borrowing costs, leading them to cut payrolls. This is why the EIU has also two pessimistic scenarios combined at a 25% probability. Under these severe circumstances, the COVID-19 would take longer to contain and real GDP growth in China would plunge to a pace unseen since 1990 (4.5% or worse), bringing down the world in recessionary territory.

So far, we are of the view that the Canadian economy is less affected than Asian economies but more than our U.S. partner due to our larger dependence on crude oil and China.