Copper is a red, shiny industrial base metal essential for global growth because of its excellent electrical conductivity. It is vital for the transition to sustainable sources of energy to ensure a clean and green future and for enabling digitalisation.

The following facts and figures help us understand this key to a green future:

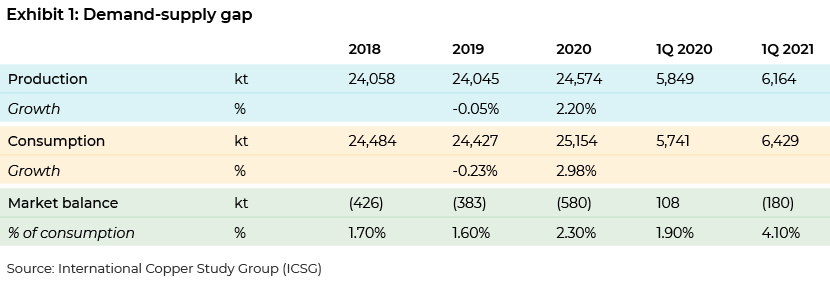

Demand for the metal is increasing and the demand-supply gap widening. Media reports indicate a wide gap of 8.2m metric tons by 2030 as the metal is used in applications powering the energy transition. We also expect demand to be driven by the recommissioning of infrastructure and manufacturing projects. Supply, on the other hand, has been under pressure for several years and is likely to remain so.

Digitalisation increases demand for computers, mobile phones and networks and, therefore, for components for these devices and systems. It also increases demand for technological infrastructure. Copper wire is used in all electrical and electronic devices. Some estimates forecast that an additional 5.3m metric tons of copper will be required to cover demand created by 42 emerging technologies by 2035(1).

(1) Source: UNCTAD

Cutting carbon emissions is another global priority. China has pledged to neutralise its carbon emissions by 2060. US President Biden has committed USD2tn to help cut emissions, and the EU targets zero emissions by 2050. To achieve such goals, governments would need to shift to sustainable energy sources, requiring additional copper for constructing the infrastructure

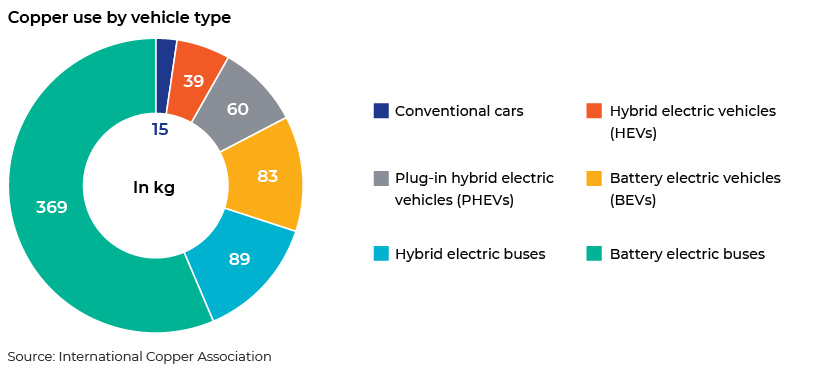

Electric vehicles (EVs) and renewable energy from solar and wind farms are projected to reduce carbon footprints. EVs also drive copper demand. It is estimated that EVs will generate additional copper demand of 1.5m metric tons in 2025 and 3.3m metric tons (forecast to be 10% of total demand) by 2030 versus less than 500 kilotons in 2020. The world’s biggest auto market, China, expects EVs to account for c.60% of vehicle sales by 2035. The US expects them to account for 50% of vehicle sales by 2030. The number of EVs is forecast to reach 7m by 2025, requiring c.5m charging ports to support them.

Exhibit 2: Copper required by vehicle type

What is behind tight supply?

Chile is the world’s largest copper producer, accounting for more than a quarter of global production, but is expected to face challenges with copper supply in the near future:

Lack of civil society support:

The Chilean mining sector’s new regulation requires increasing civil society approval, the lack of which has led to a reduction in investment in the mining sector.

Productivity and cost:

Older mines are finding it challenging to process lower-ore grades amid increasing transport wages and energy costs. The mining sector has been facing higher operating costs due to lower productivity.

Water scarcity is another challenge to the mining sector, which contributes approximately 10% to the country's GDP. The north of the country, where c.75% of copper production takes place, is the driest place on the planet. Desalination is a possible but expensive solution that would increase cost.

Routine labour strikes also hamper production. Chile’s Escondida, the world’s biggest mine, grapples with unionised employee strikes demanding wage increments. Talks have failed multiple times.

Political risk in Chile and Peru, which account for c.42% of the world’s copper production. The upcoming overhaul of Chile’s market-oriented constitution includes increasing royalties on miners. Peru’s new Marxist president pledges to redraft its constitution and take a far larger portion of mining profits from companies.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC) recently introduced an export ban on copper concentrate (the raw material for refined copper), increasing pressure on the supply side.

The tight global market for copper concentrate continues to push market leaders in the smelting and refining industry to negotiate minimal treatment charges and refining charges (TC/RCs). TC/RCs are a medium of revenue for smelters. Before the pandemic, they were double what they are now.

Amid the pandemic:

The pandemic has disrupted both demand and supply through labour crises, especially in the construction and manufacturing sectors, and the suspension of exports and imports.

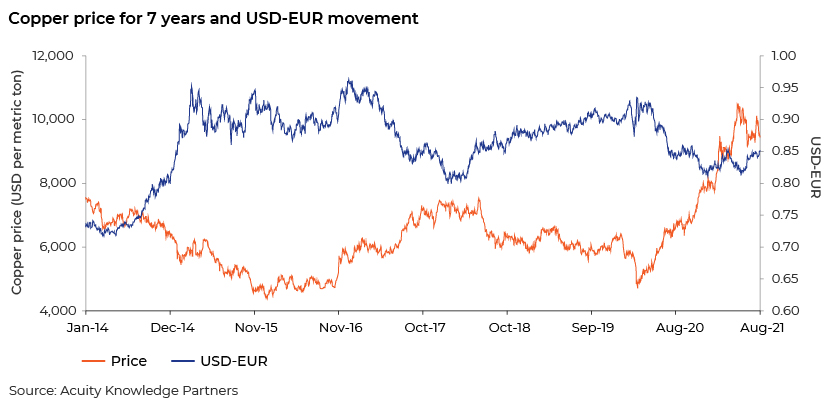

Copper prices touched their all-time high, despite the pandemic, in the second quarter of 2021, driven by the factors mentioned above that are forcing the demand-supply gap to widen. Some of the big commodity trading firms and media houses are excessively bullish on copper prices, and the price is estimated to reach USD20,000 per metric ton by 2024 (USD9,445 per metric ton on 9 August 2021 and USD6,285 per metric ton on 7 August 2020).

Higher price substitution impact (partial shift to aluminium):

Aluminium is likely to substitute copper partially due to increasing copper prices. Copper stood at USD9,502 per metric ton and aluminium at USD2,601 per metric ton on 9 August 2021. It is estimated that a price ratio of 3.65:1 could trigger the substitution of copper with primary aluminium. The wider the gap between the prices of the two metals, the greater the incentive would be to substitute copper with aluminium. Prices of aluminium are also less volatile, likely to make it a champion in the substitution game.

The world is transitioning to a phase where energy efficacy policies will be stricter on environmental concerns than fuel costs. Heating, ventilation, air conditioning and refrigeration (HVACR) are areas in which aluminium is found to be more efficient in conducting heat.

Copper could soon be replaced by aluminium in cables and wires, particularly in countries such as Brazil and China. Apart from its price advantage over copper, leading to cost savings in use in electricity lines, aluminium is lighter.

Factors balancing market prices:

US Fed rates:

Copper prices and the USD are inversely related.US inflation has reached the threshold, driving the Fed to hike rates. This has allowed the USD to maintain its strong momentum, pressuring copper prices to fall from their peak

China’s concern over price hike:

China is the world’s largest refined copper consumer and has announced releasing the metal in stages to the open market to stabilise prices. In the second stage, it plans to release c.170 kilotons of refined copper by the end of 2021.

China’s growing supply of copper scrap:

From now to 2060, more end-of-life vehicles (ELVs) and demolished buildings are expected to yield surplus secondary copper (scrap) in China. The government recently started allowing copper scrap imports in a structured and monitored manner, rapidly increasing demand for and pricing of copper scrap. China has also restarted processing scrap due to tight supply.