TSX futures edge higher after index logs fresh record high

Recent headlines involving the BRICS alliance’s deepening economic ties have caused quite a stir in the global financial community. Among the notable events of the past month is an agreement between China and Brazil to settle trades in yuan rather than USD, as well as Saudi Arabia’s comments which indicate a previously unseen openness to peg their oil prices to something other than the dollar.

With the constant stream of negative headlines, talks of “de-dollarization” have resurfaced in recent weeks, and investors have been left to grapple with a seemingly existential question: is this the end of the U.S. dollar?

The short answer is “not so fast”.

De-dollarization is old news

De-dollarization as a concept is nothing new. In essence, it represents a phenomenon whereby the role of the greenback in international trade settlements and global financial operations will diminish as countries elect to diversify their FX holdings or choose to settle trade in their own domestic currencies.

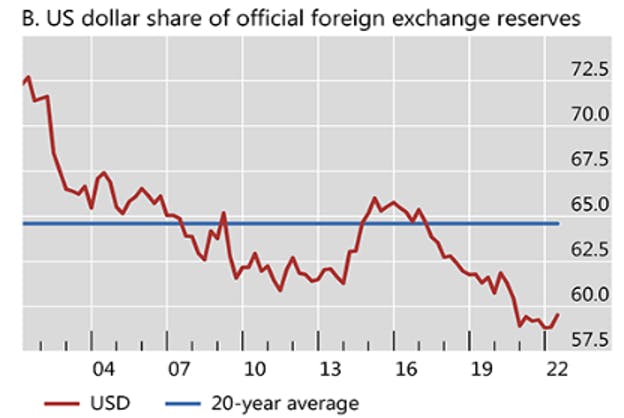

With this loose definition in mind, it’s important to look at data over the last few decades, for more context. The USD’s share of foreign exchange reserves has been steadily declining for the better part of the last 2 decades (>70% in 2000 vs. 60% in 2022), with little effect on the dollar’s relative strength:

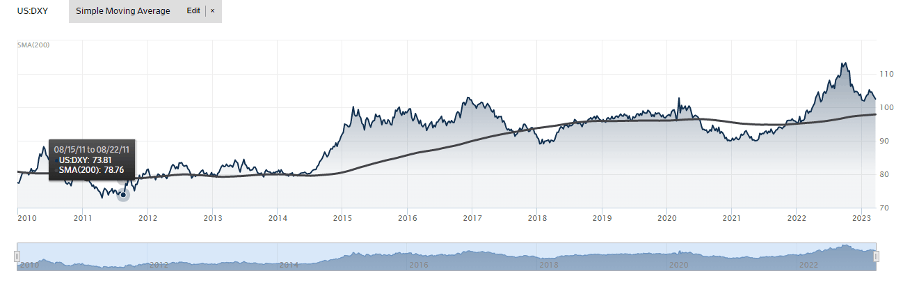

The U.S. Dollar Index (DXY), which ranks the dollar against a basket of 6 currencies, has maintained relative stability over this same period and has even been in an uptrend since 2010, with periodic moments of relative weakness:

Central banks are investors too

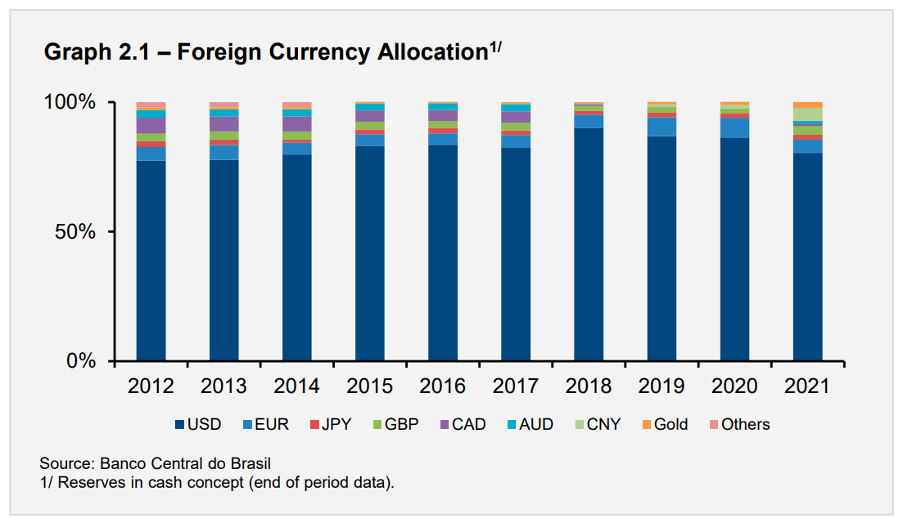

One thing that investors must keep in the back of their minds when encountering sensationalist claims about the fall of the “King Dollar” is that diversification is not unique to stock and bond portfolios. Central Banks also engage in diversification with their FX reserves, and periodically they may sell their top performers in order to prop up their own currencies.

For example, Japan sold dollar-denominated assets in the fall of 2022 in order to prop up the value of the Yen. Similarly, Brazil engaged in similar transactions throughout 2021 and 2022 as their commodity-focused economy struggled with inflation. Selling some of their USD holdings allowed them to prop up the real ever so slightly:

This is similar to an investor selling some of their Apple shares (NASDAQ:AAPL) to raise some cash for their regular bills. It speaks more about the investor (country)’s own financial troubles, than those of Apple (the USD).

The end is not nigh, but there are dangers ahead

Although the geopolitical threats facing the USD are not something to completely disregard, at the moment they seem little more than background noise in the financial media. The data so far does not support any mass selloffs of USD-denominated assets, or at least not any more than would be reasonable.

But there are other risks much closer to home that could significantly impact the USD’s relative attractiveness to other currencies, or that risk permanently damaging the U.S.’s reputation as a trustworthy borrower.

Capital goes where it is treated best. That much has always been clear. Whether it’s lower taxes, subsidies, or higher risk-free rates of return, money tends to flow where it can be the most productive. It is the reason that the USD has outperformed virtually all its competitors over the last 3 years, despite a fairly uniform increase in rates worldwide.

Along with the increased returns that could be generated from risk-free treasuries as interest rates rose, there was also the relative safety of the American economy versus the Eurozone, China, Japan, or any other developed economy.

But both of these factors seem to be fading fast, as the rate hiking cycle approaches its end (with cuts priced in later this year), and a looming government debt crisis in June. These two factors are much more likely to present problems for the USD going forward than any coalition of countries who are planning to overthrow the dollar.

How can investors protect themselves?

Predicting the downfall of the USD is as futile as any other asset price prediction. It may happen, but it will likely take longer than most people believe.

There are other risk factors to be weary of however, such as the eventual stop in rate hikes which have buoyed the dollar’s relative value over the past 2 years, and the impending debt ceiling.

The U.S. has never defaulted on its debt before, so the spill over effects are speculative at best, but it’s likely that confidence would be lost in the dollar and treasuries (at least temporarily).

In those situations, investors usually turn to safe-haven assets such as gold and silver available on the CBOE Canadian ETF Market. The iShares Silver Bullion ETF Hedged (SVR) and CI Gold Bullion Fund (VALT) are great options as they provide physical exposure to gold and silver, and most importantly it’s hedged to the CAD. This means that if the USD drops in value relative to the CAD, investors won’t lose out on the exchange rate.

This content was originally published by our partners at the Canadian ETF Marketplace.