By Kathy Lien, Managing Director of BK Asset Management.

2016 will be a defining year for the British pound -- a year when politics will overshadow economics. Considering that sterling ended the year near 7-month lows against the U.S. dollar, some of our readers may find it surprising that the U.K. was one of the best-performing G10 economies. However according to the latest figures for the third quarter, the U.K. economy grew at an annualized pace of 2.1%, which matches the pace of U.S. growth. In contrast, the Eurozone and Japan grew 1.6%, Australia expanded 2.5% and Canada contracted by 0.2%. There's also very little debate that the Bank of England will be the next major central bank to raise interest rates. Yet sterling benefited from none of this and instead weakened versus the euro, Japanese yen, U.S. and New Zealand dollars over the past 6 months. Part of the underperformance was driven by U.S. dollar strength but slow U.K. wage growth, mixed data and cautious policymakers has the market looking for rates to rise in 2017 and not 2016.

We believe the market is underestimating the Bank of England and the U.K. economy because 2016 should be a year of strong growth. Consumer spending is the backbone of the economy and sales surged in November. While wage growth slowed, labor force participation rates remain near their highest levels in 20 years and service-sector activity is accelerating according to the latest reports. As the labor market tightens and inflation bottoms out, wages should rise as well. Slow Chinese and Eurozone growth poses a risk to the economy and the manufacturing sector but the U.K. is still expected to be one of the fastest growing G10 economies in 2016.

From the perspective of growth alone, the Bank of England should raise interest rates in the first half of the year. However there are 2 primary issues holding the central bank back -- low commodity prices and the risk of Brexit. Oil prices could remain low for a large part of the year and as of November, consumer prices are running at a 0.1% annualized pace, which is far short of the central bank's forecast. Considering that the Federal Reserve raised rates with yoy inflation at 0.5%, the BoE may not need to see CPI above 1% before tightening monetary policy but they could be reluctant to do so until there is greater clarity on Britain's position within Europe.

The greatest risk that the U.K. economy and the British pound faces in 2016 is Brexit. What is scarier is that opinion polls show voters split almost 50:50 on whether the U.K. should remain in the European Union. The Paris attacks and the country's confidence in Cameron's ability to reform freedom of movement rules for EU migrants played a large role in narrowing of polls but for most of the year, support for staying in the U.K. overshadowed the resistance by only a small margin. Leaving the EU would bring a period of deep economic uncertainty that will hurt consumer, business and investor confidence. The actual cost to the economy is difficult to estimate. Supporters of Brexit say that it would save British taxpayers billions and ease their economic responsibilities to the union. However at the same time, there could be significant costs to trade, investment, and jobs. The answer lies in how the exit is structured. If Britain maintains a free trade agreement, pursues very ambitious deregulation of its economy and opens up trade almost fully with the rest of the world, the best-case scenario calculated by Open Europe, a UK lobby group, estimates that a Brexit could lift UK GDP growth by 1.6% in 2030. However in the worst-case scenario where the U.K. fails to strike a trade deal with the EU, Brexit could cost the economy as much as -2.2% in GDP growth. Realistically, the best- and worst-case scenarios are not the most likely outcomes. Predicting the long-term impact of Brexit is nearly impossible at this stage because we don't know what the terms of the new relationship will be and we won't know until well after the referendum. But in the lead up and immediate aftermath of the vote, we expect significant volatility and most likely weakness in sterling and other U.K. assets.

It is not in the Bank of England's interest to raise rates during turbulent times and considering the greatest volatility for sterling will come in the lead up to the referendum, policymakers could err on the side of caution and forgo a rate hike. Of course there's another way to look at this -- they could raise rates sooner, which would give them the leeway to cut rates later if the markets collapse. There's no set date for the in/out referendum -- it could be in the second half of 2016 or 2017, which means if the BoE wanted to raise rates, they could do so the first half and avoid conflict with the referendum.

The Brexit vote will be a defining moment for not only the U.K. but all of Europe. Aside from the political ramifications of shifting the power in the European Council, the EU as a whole would be a less attractive partner. The economic implications are unknown but there could be greater competition between the U.K. and E.U. but ultimately the short- and medium-term ramification is uncertainty, which is never good for a currency.

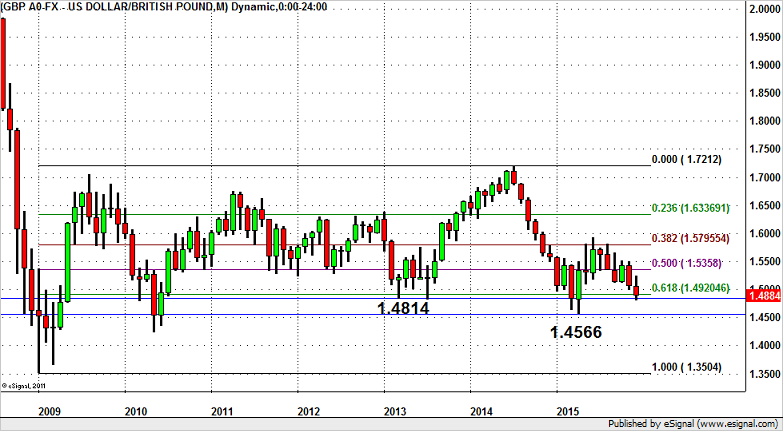

Technically, GBP/USD is very weak but there are a number of significant support areas below current levels. First we have the 2013 low at 1.4814, a level that has limited losses for the currency pair in the second half of the year. Below that is the 2015 low of 1.4566. In order for the downtrend to be officially negated, we need to see a much stronger rally in GBP/USD that takes the currency pair above 1.55. With that in mind, we believe that the wide 1.45 to 1.65 trading range in GBP/USD will remain intact in the year ahead.