by Jason Martin

If you’ve been following the soap opera that Brexit negotiations have become, one gets the impression that, though the UK's June 23, 2016 decision to split from the 28-member bloc known as the European Union seems to have placed Great Britain in some economic jeopardy, the remaining 27 EU members have little to lose from the divorce proceedings. It would appear that, whatever the consequences on the UK side, the countries remaining in the union will continue—as a group—to be a regional political and economic powerhouse.

However, though the immediate consequences have been felt in the British economy as discussed in our prior analysis earlier this week, the media appears to largely have examined the issue purely from the UK-side, generally neglecting to address any negative effects on the countries remaining in the EU.

Initially the EU was included in headlines, as individuals on both sides of the Channel worried over how their citizens residing in the other half of the soon-to-be-broken relationship would fare if they lost their current right to freedom of movement.

As both parties made clear their intent to maintain the status quo for foreign residents already established in their domain, the costs to the EU resulting from the UK’s planned departure appeared to fade from view and focus shifted to Britain’s need to pay financial obligations, the effect on its economy as future trade agreements remained in limbo, even as the pound slid, spurring inflation and forcing the Bank of England to hike rates at its most recent monetary policy meeting.

Having already examined whether the window is closing on the UK’s chances to get a good deal in our previous analysis, we'll now focus on the impact for the EU.

Fact: the EU Will Take an Economic Hit

When reading through pieces about Brexit, it’s key to remember that any future deals function as a two-way street. The costs to one side will be reflected on the other side, albeit to a larger or lesser degree.

In the worst case scenario, known as a “hard Brexit”, where the two sides fail to come to an agreement on trade, World Trade Organization rules would be applied to products sent from the UK to the EU and vice versa. Many industrial products would suddenly see tariffs added of just 2% to 3%, but cars would see a 10% tax tacked on, while many agricultural products would have a tariff of between 20% and 40%.

In fact, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) warned in its latest regional economic outlook that a “disruptive” Brexit would likely have a damaging impact on both parties.

"Under such circumstances, our concern is that economic growth will suffer, especially in the UK, but also the euro area," the IMF said (emphasis is ours).

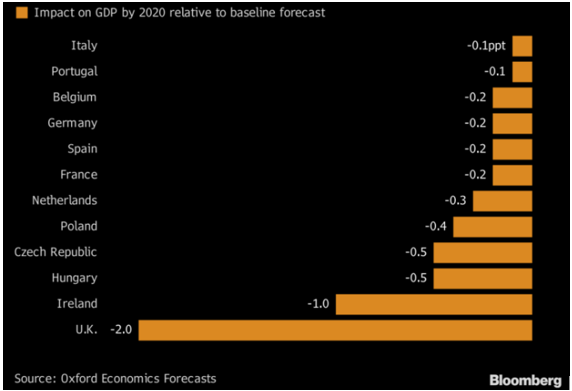

Much like the IMF, most analysts expect the British economy to be harder hit than that of the remaining 27-members. In a recent report from Oxford Economics, their analysts projected that the impact on the UK economy would be 10 times larger than that of the EU. However, the underlying point remains that damage will indeed be felt by those being left behind.

According to the report, a breakdown in negotiations leading to no deal would result in a 3.1% rise in the cost of importing goods from the EU, but the bloc would also pay 3.5% more for UK exports. And while for the UK this will apply to roughly 60% of its exported and imported goods, the impact for all EU countries except Ireland, although much less, would still be nearly 10%.

As the above graph from Bloomberg shows, while there is no doubt that the UK will feel a larger portion of the pain, the EU’s economic growth will not remain unscathed.

Will the EU Really Get Those UK-Based Jobs?

Headlines have largely focused on the “benefits” that the EU will receive from the split, with a particular focus on adjustments in the financial sector. News headlines have been awash with banks setting up contingency plans that include moving some employees and/or operations to Frankfurt or Dublin due to concern that a hard Brexit will do away with passporting rights that allow British-based firms to do business across the Channel as part of its membership in the EU.

According to the European Central Bank’s top bank supervisor Daniel Nouy, around 50 banks operating in the EU from Britain have approached supervisors to request information on how to relocate and continue operations. Furthermore, the Bank of England expects Britain to lose up to 75,000 financial services jobs after the country leaves the European Union in 2019, the BBC reported at the end of October. Of note, estimates for loss of jobs in UK financial services have ranged from as low as zero to as high as 220,000 posts.

However, the view that Frankfurt and Dublin would be the likely benefactors of those transferred jobs may not be so clear cut. London Clearing House chief executive Daniel Maguire stated near the end of October that moving its rates swaps business to an EU country from London after the Brexit was not a “fait accompli”. In fact, Maguire suggested that a move to New York could be a less costly option.

Precedent for Future Populist Departures

Beyond the immediate economic impact, the larger threat for the future of the EU may well be the precedent set by the UK in abandoning the bloc. While the outcome for Britain remains to be seen, the break from the union established to bring Europeans closer together paves the way for the burgeoning wave of populism throughout the region that protests against immigration and the lack of political and economic freedom, particularly for those members who also form part of the euro zone, the smaller monetary union inside the larger EU.

The single currency has shown a stronger recovery than the pound, which is still down 12% against the dollar. To the contrary, the euro is currently up nearly 4% against the greenback since the June 23, 2016 referendum. On the one hand, market participants appeared to factor in a lesser negative impact for the euro area despite the uncertainty surrounding Brexit negotiations. The European Central Bank has also supported the currency as the euro area monetary authority took its foot off the accelerator and began to follow in the footsteps of the Federal Reserve with the removal of accommodative policy in the wake of strong growth readings, particularly in Germany.

At the beginning of this year, market concern focused on the possibility of far-right election victories in the Netherlands, France and Germany. With the Brexit vote in the rear view mirror, concern was that euro-sceptic parties could come to power and push not only for an exit from the European Union but the smaller euro zone as well.

However, as events during 2017 developed, the euro began to climb as “disaster” was avoided and the established parties in the aforementioned elections retained control. Though populist movements did gain votes, they weren't sufficient to position the parties enough to reach full power.

Markets breathed a sigh of relief after the results of each of the elections but the threat of disintegration has recently prominently resurfaced. Political instability in Spain, with its Catalan region attempting to declare independence in what would also have been a de facto break from the EU, put pressure on the euro and remains unresolved as of this writing, with upcoming elections in the autonomy on December 21.

A victory in Austria’s general election by the right-wing conservative People’s Party on the back of its anti-immigration platform has also put nerves on edge, along with the election of populist Andrej Babis as the prime minister in the EU’s Czech Republic. As well, Italy is standing by while its two richest regions hold referendums to receive more autonomy. All are ongoing evidence that the EU’s status quo is anything but stable.

In short, the EU’s unity remains fragile and the UK’s move to leave a relationship that slightly over half of its citizens weren’t happy with provides a framework for similar moves if populist groups still in the bloc eventually reach power.

No one is actually arguing that the EU won’t be hurt, economically and ideologically, by the UK’s departure. It’s simply a theme murmured in the background as EU politicians turn up the volume on the need for British negotiators to “provide clarification,” concurrently deflecting scrutiny from the union's own potentially negative outcomes.

While that might be an effective diversionary tactic, one would do well to remember that there are always two parties involved in every divorce. The EU will not emerge undamaged from the Brexit. However, just how far the process goes to break up the rest of the 27-member family remains to be seen.