The opinions expressed here are those of the author alone and do not represent the views of any associated entities.

During the financial crisis, house prices in the US fell, in part due to rising interest rates (sound familiar?). The result of these higher interest rates was ultimately a countless number of underwater mortgages - a situation that arises when a homeowner owes the bank more than their home is worth. Many Americans that found themselves in this situation chose to declare bankruptcy. Why stay on the hook for a $400k mortgage for a house only worth $300k when you could start fresh?

It’s not hard to imagine a similar sort of situation developing in Canada. Indeed, we recently experienced an interest rate-driven drop in home prices. Although prices rose after The Bank of Canada paused its rate hiking cycle earlier this year, the market cooled off again following the most recent rate hikes.

With half of Canadian households barely able to pay their bills, it’s not hard to imagine a scenario where home prices fall even further, and Canadians start to default on their mortgages. Indeed, we are already seeing people being forced to sell because they can’t afford mortgage payments that rose along with interest rates.

If this sort of US circa 2008 situation did play out in Canada, who would be left holding the bag?

The natural assumption, at least for me, is that the banks that gave out the loans that went bad would be most at risk. I was surprised then to realize that if a wave of foreclosures were to hit the Canadian market, the federal government, not the banks, would be most at risk.

Today we’ll discuss how an obscure policy left our public finances exposed to the housing market while contributing to our economic issues.

The interest rate on a loan is, at least in theory, supposed to be determined by the chance of the loan being repaid. For example, you would charge more interest to an unemployed acquaintance asking to borrow money than you would to a reliable friend with a stable job.

It’s strange then, that Canadian banks charge a lower interest rate for riskier mortgages.

Here are some mortgage rates I pulled from HSBC’s website:

High-ratio borrowers, with a down payment of less than 20% of the purchase price, are charged a lower interest rate than buyers with larger down payments.

Lower interest rates for riskier loans might go against conventional logic. However, they make more sense once you consider Canada’s mortgage insurance regulations, which stipulate that homes purchased with a down payment of less than 20% must have insured mortgages.

When a bank gives a mortgage to a high-ratio borrower, the bank takes out insurance that protects against the default of that mortgage. The cost of the insurance is typically added to the mortgage. This explains why high-ratio borrowers get a better interest rate: Despite having a lower down payment, these mortgages are not actually risky for the banks, since they have protection in the event of a default.

Mortgage insurance transfers the risk of default from the lender to one of three main insurers. The Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation (CMHC), a government-run agency, was the primary mortgage insurer prior to the pandemic. In 2020, CMHC smartly attempted to “curtail excessive demand and unsustainable house price growth” and “discourage homebuyers from taking on more debt than they can afford” by making it harder to qualify for mortgage insurance. Higher standards for credit scores and debt-to-income ratios were put into place.

Privately-owned and operated Sagen (formerly Genworth) and Canada Guaranty Mortgage Insurance Company (CGMIC) used this as an opportunity to gain market share. They did not follow CMHC in tightening mortgage insurance qualification criteria. Former CMHC CEO Evan Siddall pleaded for lenders, Sagen and CGMIC to “put our country's long-term outlook ahead of short-term profitability”. Nevertheless, with the blessing of Sagen or CGMIC, lenders continued to give out high-ratio mortgages that wouldn’t have qualified under the more stringent CMHC criteria.

Over the course of the following year, CMHC’s share of the mortgage insurance market dropped by about half, from 46% to 23%.

After Sidall's departure from CMHC in 2021, in an attempt to regain market share, CMHC reversed course, loosening its qualification criteria to come back in line with the private insurers. So much for discouraging homebuyers from taking on more debt than they can afford.

Altogether, there are now $560 billion of insured mortgages in Canada. A growing proportion of these are (or are close to being) underwater. This is worrisome for both insurers and the lenders that they insure.

Now, you might be wondering, why do lenders believe that insurers will be able to pay them what they are owed if borrowers start defaulting on their underwater mortgages?

Sagen, for example, has insured nearly $200 billion of mortgages, but only has a few billion dollars in capital available. If there were ever a big wave of defaults, it doesn’t appear that Sagen would be able to cover the losses that banks might incur.

The answer: The banks don’t actually care if insurers can pay them back. The glue that holds this whole system together is a guarantee from the Federal government.

In exchange for a small portion of the premiums collected by insurers (3.25% for CMHC, 2.25% for private insurers), the government “backstops" mortgage insurance contracts (100% coverage for CMHC insured mortgages, 90% for privately insured mortgages).

An example might be illustrative.

Imagine a young couple that has saved up the minimum 5% down payment of $25k for a $500k condo. Their lender gets mortgage insurance for $19k from Sagen (4% of $475k). The cost of this insurance is added to the couple’s initial mortgage, bringing the total amount they owe to $494k (rather than $475k). Notably, this mortgage is close to being underwater from the start. Sagen pays the government just $475 (3.25% of $19k) to guarantee the loan.

If condo prices were to suddenly drop by 30%, the couple would still owe the bank $494k, but their home would only be worth $350k. With a net worth of negative $144k, it’s not far-fetched to think that the couple would decide to default on their loan and declare bankruptcy, especially if higher interest rates were making their mortgage tougher than expected to afford.

The bank would take control of the property and sell it for $350k, and Sagen would be responsible for paying back the other $144k the bank is owed. If this were an isolated incident, Sagen would have no problem fulfilling its obligation to the bank. However, if defaults were widespread, which they probably would be if prices were to fall significantly, Sagen might not be able to satisfy its commitment. In that case, the government would owe the lender $130k (90% of $144k). That’s a lot of risk to take on for $475!

Notice that in the above example, no party is incentivized to slow down the risky lending.

Due to years of skyrocketing house prices, prospective homeowners are incentivized to overleverage themselves, taking on bigger mortgages than they can afford. They can’t wait until they save up a sizable down payment because prices are rising faster than they can save.

Banks are incentivized to give out as many high-ratio mortgages as possible because, from their perspective, the federal backstop has made these loans essentially risk-free.

Insurers are incentivized to sell as much insurance as they can, no matter the quality of the mortgages they are insuring. The more insurance they sell, the more money they make. Qualification standards for mortgage insurance are dictated by private companies that prioritize profits. If Sagen goes bankrupt because it was overleveraged, insuring more and worse mortgages than it should have, Sagen CEO Stuart Levings won’t have to give back the millions of dollars he was paid to sell all of that insurance.

Any wave of defaults that hits the Canadian market would be primarily composed of insured mortgages, which would be the first to go underwater because owners with insured mortgages generally have less equity in their property. In this scenario, the financial stability of insurers is the only thing standing in the way of the taxpayer footing the bill to make lenders whole.

Didn’t we learn anything from the 2008 financial crisis, when the taxpayer ended up on the hook for the bills of financial institutions that took on more risk than they should have?

Siddall has previously said that "There is a dark economic underbelly to this business that I want to expose". I hope it’s now clear what he meant.

Mortgage insurance sold by CMHC, Sagen, and CGMIC is only credible because of the federal backstop

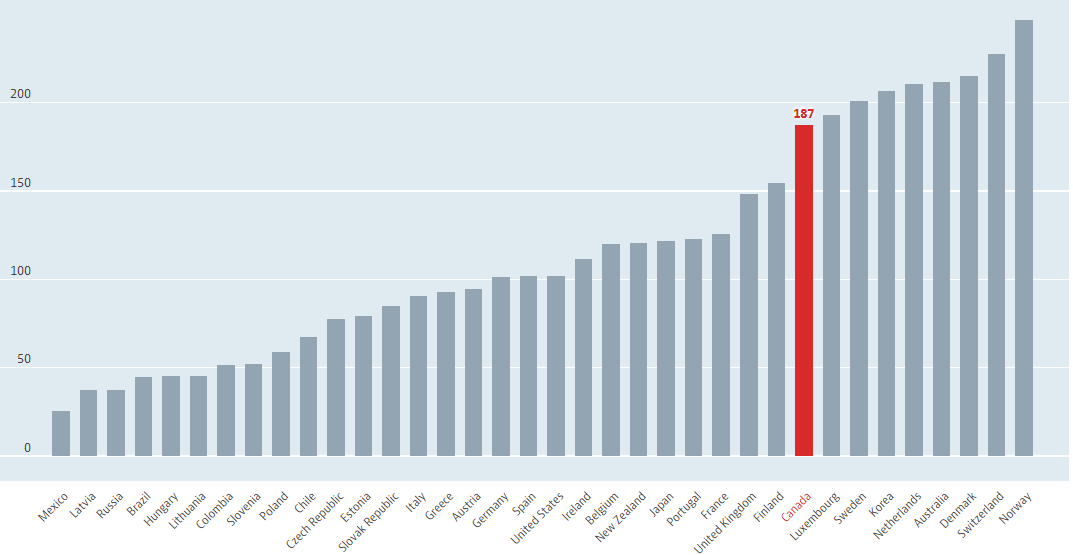

It might seem helpful that the government has made it appealing for banks to give mortgages to people with small down payments, allowing them to buy homes they otherwise would not be able to afford. However, letting people use more leverage is not a sustainable strategy for dealing with our affordability issues. It does nothing to address the root problems causing our high home prices, like low supply, and the less often mentioned high demand. Instead, it just allows people to bid up prices further while putting themselves, and our entire economy, at risk by taking on massive amounts of debt. Canadian households are now one of the most indebted in the world, with a debt-to-income ratio of 187, nearly double that of the US (102). Our high debt levels make our economy less resilient to shocks, and thus more fragile.

The backstop has driven an incredible amount of money away from productive parts of the economy

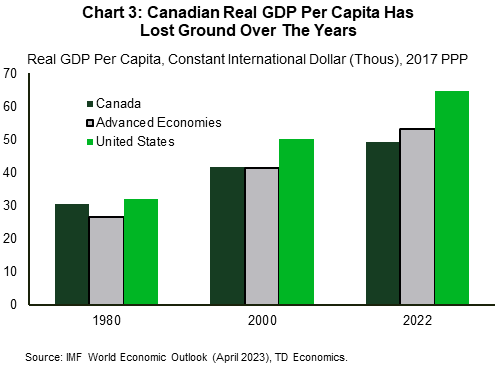

More concerningly, Canada is predicted to have the worst-performing economy of any of the 38 OECD countries over the next four decades.

Our poor economic prospects can be attributed to a decline in spending on research and development, and a lack of business investment, which has fallen by 17.6% since 2014, compared to an increase of 23.5% in the US.

Experts argue that “Our country badly needs a new strategy to promote economic prosperity through a shift in lending and borrowing from mortgage loans to business loans”. But why would banks ever shift to lending to businesses, when the government has made lending to highly leveraged homebuyers risk-free?

Where the money goes determines what grows

In Canada, in part because of the backstop, money goes into the housing market through high-ratio mortgages, driving up prices and debt levels.

Without the backstop, lending to high-ratio borrowers would be less appealing to banks, and some of this money would end up being used more efficiently by businesses to create better jobs, products, and services.

The backstop, in its current form, is harmful. It is administered by the federal government, yet our Prime Minister thinks that housing is not a federal responsibility.

With the swipe of a pen, our federal government could make changes to the backstop to reduce high-ratio lending. This would help affordability by reducing highly leveraged purchases, dampening demand and prices, while promoting productive economic growth, by encouraging lending outside of real estate.

One effective strategy would be to remove the backstop for everyone but first-time homebuyers, which would reduce demand from highly-leveraged investors by making lending to them riskier for banks. Another tactic would be to stop blindly guaranteeing all mortgage insurance contracts, which currently only conform to questionable standards set by private companies, and start to backstop only contracts that meet government-dictated standards for things like credit score and debt-to-income ratio. This would allow the government to control the amount of risk that is taken on by both borrowers and the taxpayer.

Instead, our federal government is focused on relatively small projects like building a couple hundred affordable homes.

It’s time for us to recognize that what we really need is more comprehensive reform. Our economy is broken. Updating the federal backstop would be a good first step toward fixing it.

That’s all for this time.

As always, I would love to hear any thoughts, comments, or concerns you might have about all of this. Feel free to reach out!

This content was originally published here.