Last week, we learned that the Consumer Price Index rose by 0.47% in January, well above expectations. Excluding food and energy, the news was not much better, with a 0.45% advance. It was a disappointment and a familiar one.

January has often been hotter than expected over the past several years. Given these new data, how worried should we be about inflation for this year?

Keep Calm.

It’s one month of data. As Fed Chair Powell said last week, the Fed doesn’t overreact to a few months of good data or to a few months of bad data. We should not either. The January CPI was not good and slowed progress toward the Fed’s target. Even so, it is unlikely the start of a re-acceleration in inflation.

Last year, we saw that the firm prints in the first quarter turned into soft prints in the summer. As a result, the year saw further progress: core CPI was 3.2% in December 2024 versus 3.9% in December 2023 despite its hot start. And it’s not just last year; January CPI has been a source of repeated upside surprises. This year, it is too soon to write off disinflation or Fed rate cuts in 2025.

This year’s surprise in CPI might not be as worrisome as last year’s.

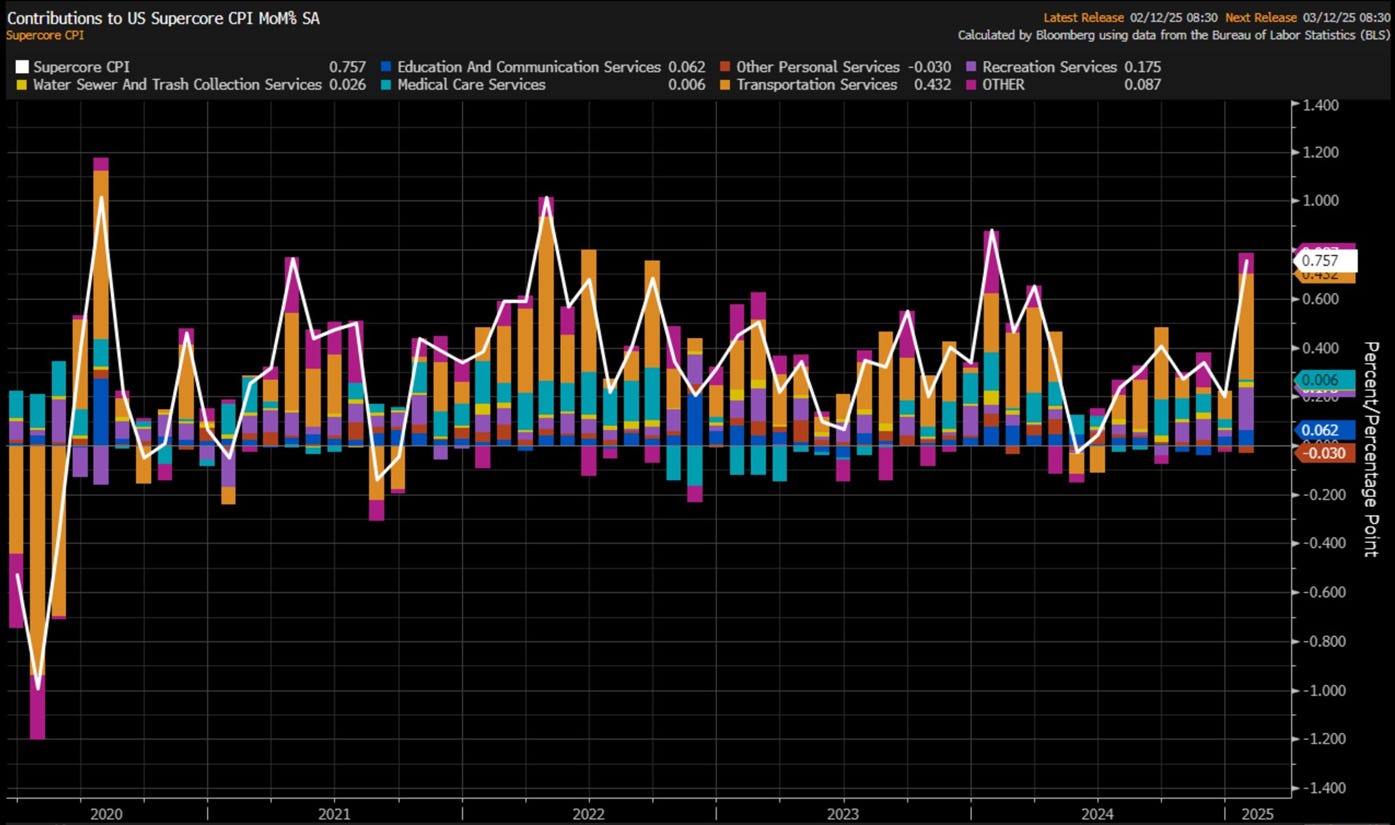

As one example, core services excluding housing—known as “supercore”—surged similarly this January and last, but it was less broad-based this year. Transportation services (in orange, led by motor vehicle insurance and airfares) and recreation services (in purple, led by subscription services and events), about one-third of the supercore category, accounted for almost 80% of the increase this January. Last year, the surge was spread more evenly across the supercore categories. Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Bloomberg.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Bloomberg.

Narrow heat is less worrisome since it is more likely to be special factors or noise. Broad-based heat, in contrast, could be signaling a broad-based cause like a too-strong labor market or excess demand.

That’s not the current signal. Overall, the January CPI looks like noise, incomplete rebalancing in pandemic-disrupted markets like motor vehicle insurance, and some start-of-year re-pricing effects.

PCE inflation—the Fed’s preferred measure—in January will likely be more moderate at 0.25% since some of the prices it uses from the PPI, like hospital prices, came in soft. That does not negate the CPI but offers another perspective on inflation.

Some Concern.

While January 2025 is only one month, it’s not the only disappointment in recent months. Core CPI has been 0.3% or higher in the past six months except December. There is some concern that disinflation is stalling with inflation still elevated.

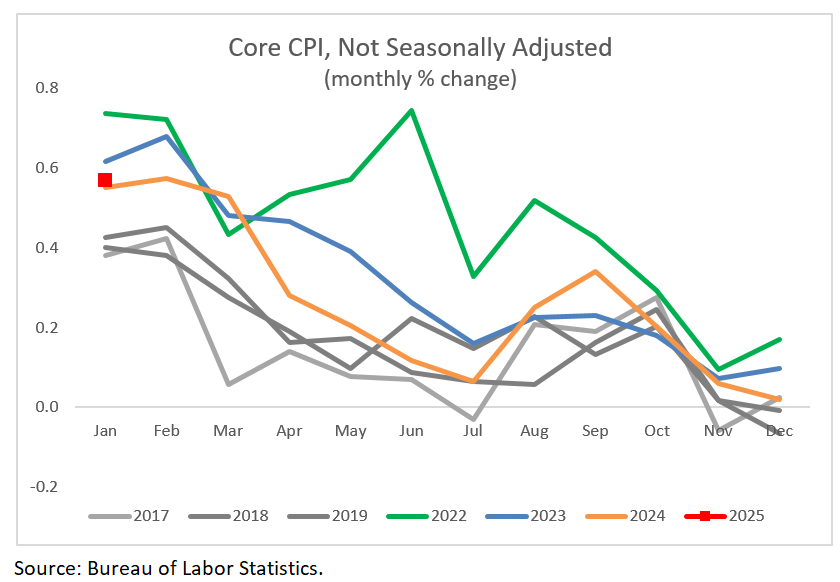

The surprising heat in January is unlikely to be just a statistical artifact that will wash out as the year goes on. January is a common time to raise prices, as seen in the non-seasonally adjusted CPI data.

Seasonal adjustment aims to remove the regular calendar pattern so the monthly changes are comparable. It does not affect the change for the year as a whole. Some have argued that the adjustment has been insufficient post-pandemic, and seasonally-adjusted data in January remain systematically higher and other months, on net, lower—a problem referred to as residual seasonality.

Formal tests of residual seasonality are sensitive to the exact specifications, and the spending categories showing strength in January have varied. Even so, the experience in recent years showed that it is best not to overreact to hot months early in the year or cool months later in the year.

However, even before the seasonal adjustment, the latest data are disconcerting. Unlike the prior two Januarys, non-seasonally adjusted core CPI in 2025 did not move down further toward the pre-pandemic pace.

There are likely idiosyncratic factors, but it is consistent with stalled disinflation. The Fed’s 2% target is comparable to 2.3% to 2.4% in CPI. Core CPI is now at 3.3%, which is still a notable gap. Inflation on par with last year is not sufficient to attain the target. In that regard, 2025 is not off to a good start, but again, it’s one month.

A Risk.

Most worrisome, the January CPI underscores the inflation risks from economic policies like tariffs.

Many businesses appear to still have higher pricing power than before the pandemic, allowing them to pass along higher costs to consumers and maintain profit margins. In such an environment, new cost shocks from the administration’s policies, like tariff duties on imported goods, could cause even more inflation than a comparable policy enacted in a low-inflation environment.

The cost shock could be sizeable. Less than a month into the Trump Administration, a wide-ranging tariff policy is taking shape. An additional 10% tariff on all Chinese imported goods is in place, a 25% tariff on Mexico and Canada was enacted and suspended until March 1, a 25% tariff on all steel and aluminum imports is set to begin March 12, and an official study of reciprocal tariffs, in which the US matches the tariffs imposed on it, is due April 1.

President Trump has threatened other tariffs, including on the European Union, motor vehicles, and pharmaceuticals. It is uncertain what the actual set of tariffs will be and how long they will last, but the potential size is substantial.

Who ‘pays’ the cost of the tariffs depends on pricing power. A wide range of studies of tariffs during the first Trump administration in 2018-19 found that US importers initially incurred the full cost of the tariffs with little offsetting reduction in price from the foreign exporters (Amiti et al, 2019; Fajgelbaum, et al, 2020).

The degree to which US importers passed the cost of the tariff on to US consumer prices as opposed to reduced profit margins or other adjustments varied. The consumer price of washing machines (Flaaen et al., 2020) and installed solar panels (Houde and Wang, 2024) rose by even more than the tariff, while other consumer goods Cavallo et al., 2021) showed little increase in price. Businesses with more pricing power can pass along the cost.

Unlike the first Trump trade war, when overall inflation had been running below the Fed’s target for years, inflation has been above target. Businesses have pricing power. The potentially large increase in tariffs this year in an environment of still elevated inflation is likely to lead to even larger increases in consumer prices than in the earlier round of tariffs before the pandemic.

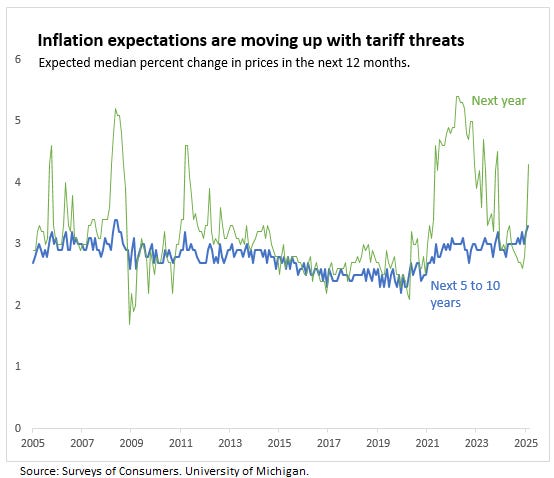

There are signs that people expect tariffs to boost inflation this year. In early February, the median one-year ahead inflation expectations jumped to 4.3% from 3.3% in January—the largest one-month increase in a decade.

The Michigan survey largely attributed the jump to the possibility of tariffs. It showed that the daily year-ahead inflation expectation estimates increased after two key announcements by Trump on tariffs.

Also, one-third of respondents spontaneously mentioned tariffs in the interview, up from less than 2% before the election. Given the recent experience with higher inflation, consumers are primed for the tariffs to be inflationary. The expectations can be self-fulfilling and might discourage the Fed from ‘looking through’ inflation caused by tariffs.

In Closing.

The extra heat in the January CPI itself is of limited concern for the path of inflation this year. Idiosyncratic factors and uneven but ongoing adjustments from pandemic disruptions appear to be key drivers, and January will likely show progress with PCE inflation. The path back to the Fed’s target remains in place, albeit slow.

The bigger worry that the hot January CPI reinforces is the inflation that new cost shocks such as tariffs could cause. Inflation remains elevated, and businesses have had experience raising prices to cover costs in recent years.

In this environment, the risks are greater that economic policies like tariffs, which raise business costs, will be passed on fully to consumers through higher prices.