As equity markets go to hell in a hand basket, and capital markets react to the additional safe haven flows, analysts are left wondering if Asia is facing a repeat of the 1997 financial crisis.

The initial salvo of CNY devaluations is likely to have a marked impact throughout Asia as major trading partners watch their exports becoming less competitive. Subsequently, many Asian nations are now experiencing significant portfolio outflows that are likely to pose some specific challenges to their external balances.

Vietnam was the first country to respond, by devaluing the dong in hopes of maintaining their export receipts, but is unlikely to be the last. In particular, Thailand is likely to cut rates at their Central Bank meeting in September. The Thai nation has been buffeted by a range of internal domestic disputes and the subsequent CNY devaluation is likely to hurt one of their mainstay industries, car part manufacturing. Malaysia also faces deteriorating conditions, and in fact, the ringgit is currently in rout. The reality is that any potential slow-down in China will directly impact much of the Asian regions' trade.

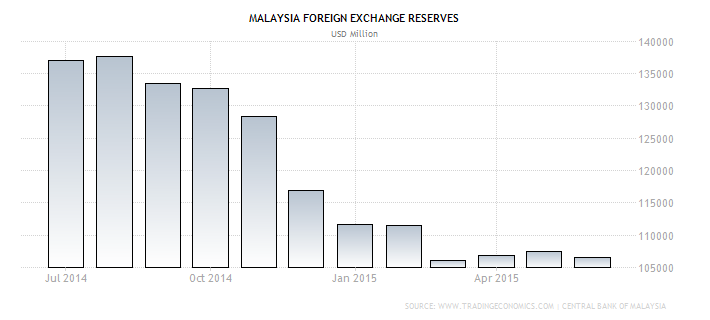

As terms of trade start to deteriorate, the state of countries' foreign reserves will start to come into focus. The relative personal and government debt levels is also likely to be watched closely as, in particular, Thailand’s debt has largely financed their expansion of late. The reality is that as the various currencies decline, the dollar denominated debt starts to weigh heavily upon the economy. This is especially the case as FX volatility becomes problematic, hence the importance of foreign currency reserves.

Across the region, external debt denominated in US dollars totals some 50% of commitments, representing a significant headwind as currencies decline. Subsequently, the FX reserves should be watched closely as central banks lean upon them to support their economies.

Although the potential for another Asian financial crisis is real, especially given the relative debt loads, what has changed this time around is the level of FX reserves. Most nations possess significant levels in contrast to the 1997 downturn. This means an additional cushion is available to weather any potential storm.

Malaysia is largely the exception to the above as their FX reserves have depleted significantly, in line with the ringgit depreciation. In fact, their net FX Reserves would barely cover even short term debt payments if required. Subsequently, Malaysia is in fairly bad shape for a long and drawn out downturn.

Overall, the region is facing a period of deteriorating exports and pressure from both currency depreciations and a larger slowdown in trade. However, Asia is structurally and economically stronger than it was during the 1997 crisis. This means that any `financial crisis’ is likely to be more of a general downturn than any form of dire straits, with Malaysia being the obvious exception.

So sit back, sip your Tiger beer on a beach in Koh Samui, and short the Malaysian ringgit.