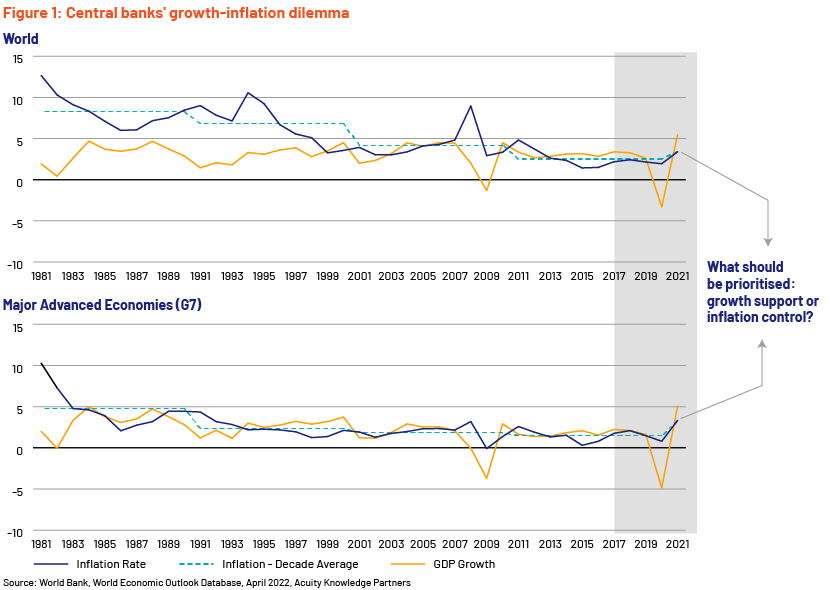

When members of the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) express vastly divergent views in their deliberations, it is quite a challenge for the chair to maintain consensus while making the right decision. The quandary of central banks is understandable. After three consecutive years of slowing economic growth since 2018, including a sharp contraction just a year ago, the global economy was amid a nascent rebound in 2021 when inflationary indications began to emerge. With much of trade and manufacturing affected by battered supply chains due to the pandemic and limping back to normalcy, allowing the evolving growth a reasonable runway seemed the obvious choice, particularly as variants of the pandemic kept popping up in one region or another. Hence, the initial reaction was to label inflation “transitory” and continue with loose monetary policies. However, after almost a decade of monetary slack, inflation had been more overdue than economic growth. By late 2021, while mulling over dropping the transitory tag, central bankers were well aware that they were likely to be either ahead of or well behind the curve. Aversion to disrupting the status quo implied the latter.

Increasingly hazy macro landscape as risks manifest

Not all price increases can be attributed to the abundance of cheap money. The shift in dynamics due to the pandemic has also led to demand-supply mismatches, for example, in the global semiconductor market. Secular growth in sales of electronic devices, cloud services, 5G networks and AI services as well as pent-up demand for automobiles have fed into the persistent upward spiral in prices of integrated circuit (IC) chips since the pandemic has started to wane. Russia’s prolonged invasion of Ukraine is also amplifying price pressures, including from energy products (petroleum, natural gas, kerosene and LPG), food products (such as wheat and edible oil) and semiconductors (such as palladium). These supply constraints are becoming increasingly difficult to resolve against the backdrop of a widening rift between Ukraine, backed by Western powers, and Russia, and China’s zero-tolerance approach to localised COVID-19 outbreaks. In the case of Ukraine and Russia, the more both sides harden their stance, the more difficult it would be to restore efficiencies in the future. In the case of China, concerns are that the longer China sticks to its zero-tolerance policy, the more difficult it would be for its citizens to achieve the immunity necessary to completely rid itself of the pandemic.

The governments' somewhat slow response to help monetary authorities alleviate fears of inflation demonstrates that they, too, were not expecting the war to extend this long. With US inflation reaching a four-decade high, the Biden administration suggested in late May that Trump-era tariffs on Chinese imports be reviewed. As a positive side effect, this may soften the trade spat between the two economic giants. The story of executive actions is similar across the Atlantic, with European countries lowering fuel and payroll taxes, abolishing surcharges and providing rebates on electricity bills and transport as the conflict in the East lingers. In Asia, the likes of China and India have continued to trade with Russia throughout the war to keep their energy bills down, while lowering import tariffs for ferrous raw materials and hiking export duties to cool domestic prices.

Despite the fiscal support, the central banks are in for protracted combat against inflation, as boosting supply seems to be a very lengthy process due to technical or geopolitical limitations. The only way, then, seems to be to squeeze money out of the system to curb demand to match supply. The extent of this increase in borrowing costs now appears to be faster and farther out than it would have been if it was not behind the curve. The Federal Reserve has hiked interest rates by 3% in FY22 – the most since 1980. This is supplemented by shrinking its balance sheet at a rate of c.USD95bn per month now. The effects of these moves are beginning to show, with many start-ups announcing mass layoffs in 2022. With further interest rate increases in the offing, a recession could be created even as the inflation engine moves on – this is called stagflation when prolonged.

Certainly not a promising near-term prognosis for stocks

The bells are already ringing for equity markets, with most global equity indices in the correction zone (down more than 10% from their most recent peaks in late 2021/early 2022) and a few in the bear-market zone (more than a 20% decline from recent highs).

If the events continue to unfold in this direction, stocks may continue the gradual, volatile slide down (unlike the steep waterfall in 2020). Even as the overcast seems to be getting darker by the day, it is important to recognise and capitalise on the pockets of value emerging in resilient, secular-growth businesses (such as cybersecurity) that are not impacted much by the tighter availability of capital and are likely to come out stronger from the inflationary currents.

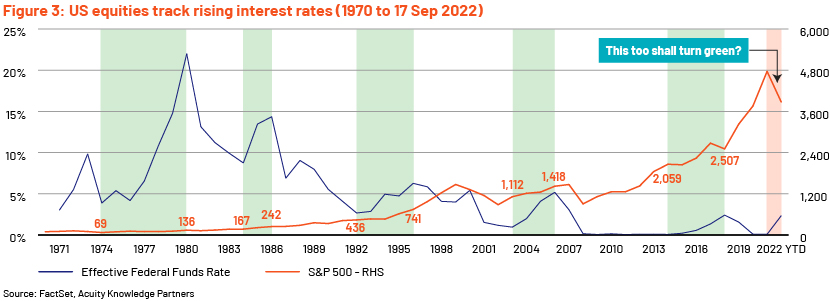

But longer-term gains are possible on equities during steady rate hikes

In addition to the narrower pockets of value outlined above, there is a broader silver lining to the cloud as well. Markets have a history of overcoming the initial hiccups and growing through longer periods of gradually increasing interest rates, as exemplified by the US (refer to Figure 3) – by far the largest constituent of any global index. Value realisation should not take long once banks and governments are able to collectively avert the prospect of extended stagflation and shift to a more predictable and moderate interest rate hike trajectory.