Fitch’s recent downgrade of the U.S. debt rating alarmed investors as the deficit and debt steadily increased. The downgrade sent 10-year Treasury bond yields above 4%, causing concern about America’s deteriorating financial condition. The problem is that if radical steps aren’t taken to curb spending, such will cause interest rates to rise. To wit:

“The U.S. borrows in its own currency and will never actually default involuntarily as long as it has a printing press. As rising rates push that financing need higher, though, the ability of the U.S. government to change the fiscal path without politically disastrous measures like cutting entitlements or by overtly printing money is becoming more limited.

If no such radical steps are taken then it almost certainly means paying more to borrow. That rising risk-free-rate will crowd out private investment and dent the value of stocks, all else being equal.”– WSJ

Such certainly seems like a logical conclusion. However, the key to the statement is in the last sentence. Many bond bears suggest that rates must rise as deficits increase and more debt is issued.

The theory is that at some point, buyers will require a higher yield to buy more debt from the U.S. Such is perfectly logical in a normally functioning bond market where the only players are the individual and institutional bond market players.

In other words, as long as “all else is equal,” rates should rise in such an environment.

However, all else is not equal in a global economy where government debt yields are controlled by Central Banks colluding with Governments to maintain economic growth, control inflation, and avoid financial crises.

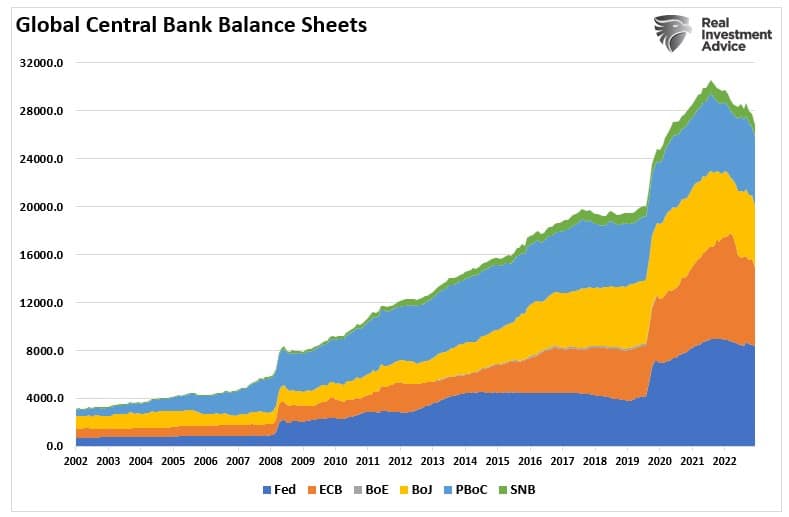

Such is evident in the chart below. Since 2008, Central Banks globally have been buyers of global debt.

Why have Central Banks engaged in such a massive bond-buying program? To provide liquidity to combat the deflationary forces of debt and keep global economies out of recession.

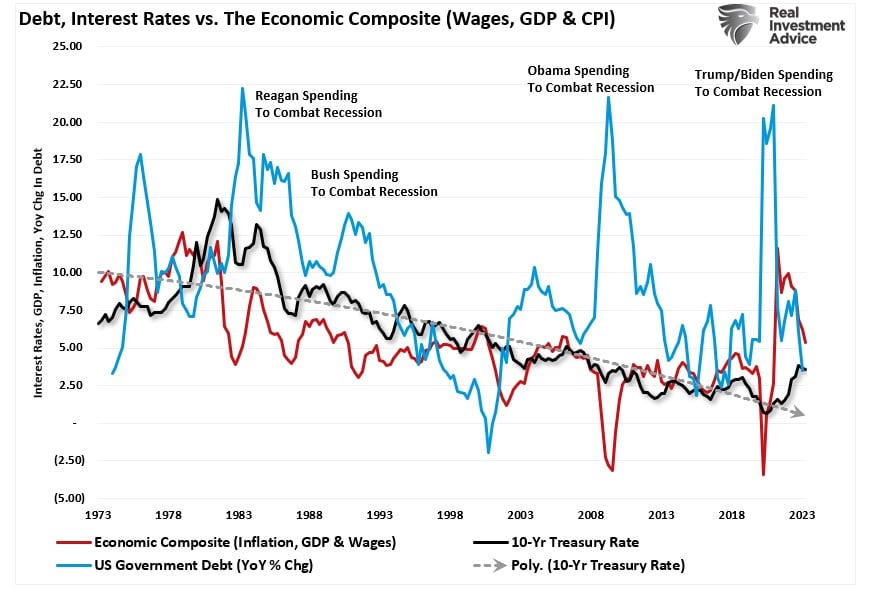

As shown, since 1980, each time the economy was dealt a recessionary blow, the Government responded by increasing debt. However, more debt resulted in a continued decline in inflation, wages, economic growth, and interest rates.

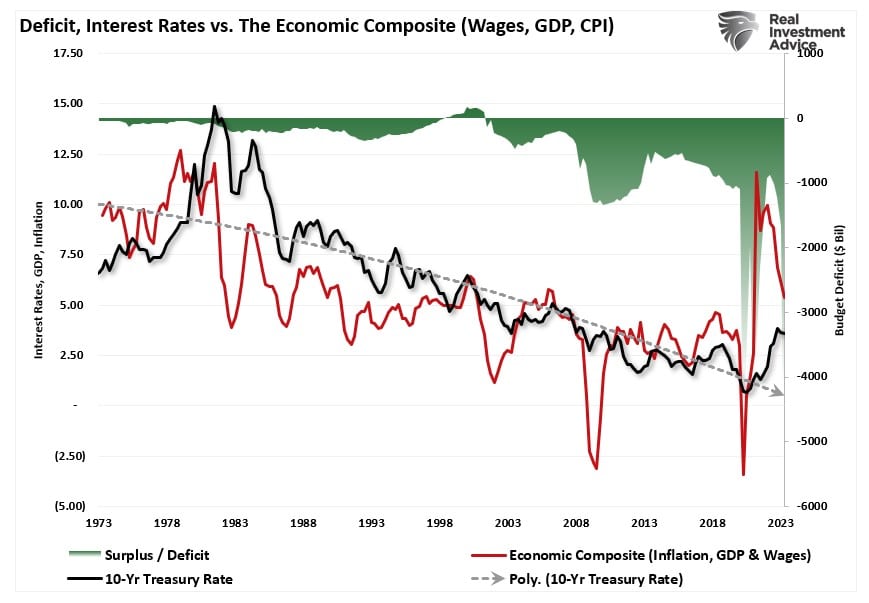

The analysis becomes clearer when viewing the economic composite against the deficit.

The expectation is that “this time is different.” More debt and more significant deficits will lead to higher interest rates. However, since 1980, such has not been the case.

(The exception was in 2020, when sending checks to households and shuttering the economy, creating an inflation spike.) More importantly, the Federal Reserve and the global Central Banks remain trapped.

The Fed Remains Trapped

Before 2020, the Federal Reserve wanted higher inflation. However, after the failed experiment of shuttering the economy and sending checks to households, the Fed now wants lower inflation.

Ultimately, the Federal Reserve will get its wish as rising debt levels foster slower economic growth rates and disinflation.

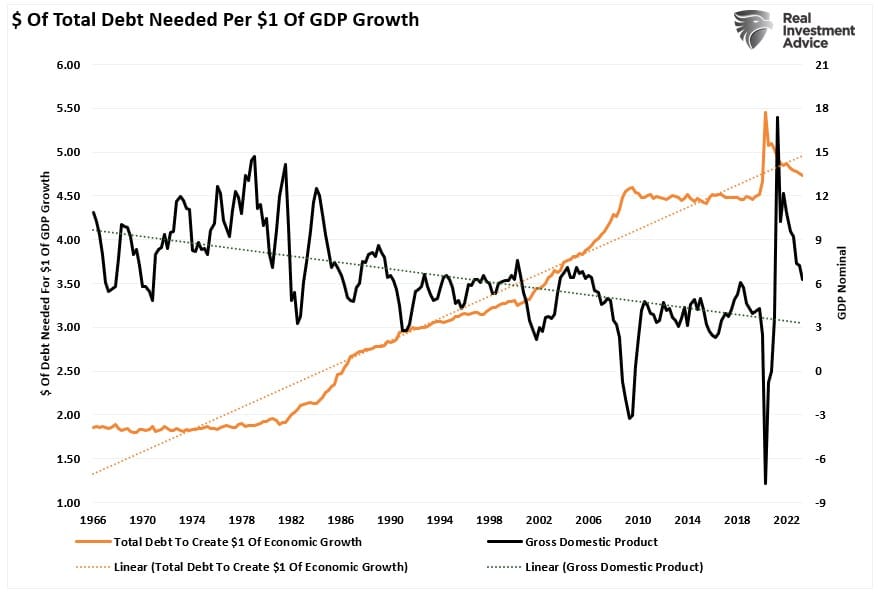

Since 1980, increasing debt levels have been required to create $1 of economic activity. At nearly $5 of debt to create $1 of economic activity, the ability to foster more robust economic growth and inflation is unlikely.

Even if the “bond bears” are correct, and increasing debt levels and deficits do cause higher rates, Central Banks will take actions to push rates artificially lower.

At 4% on 10-year Treasury bonds, borrowing costs remain relatively low from a historical perspective. However, we still see signs of economic deterioration and negative consumer impacts even at that rate.

When the leverage ratio is nearly 5:1 in the economy, 5% to 6% rates are an entirely different matter.

- Interest payments on the Government debt increase, requiring further deficit spending.

- The housing market will decline. People buy payments, not houses, and rising rates mean higher payments.

- Higher interest rates will increase borrowing costs, which leads to lower profit margins for corporations.

- There is a negative impact on the massive derivatives market, leading to another potential credit crisis as interest rate spread derivatives go bust.

- As rates increase, so do the variable interest payments on credit cards. Such will lead to a contraction in disposable income and rising defaults.

- There is a negative impact on banks as rising defaults on large debt levels erode capitalization.

- Rising interest rates will negatively impact already underfunded pension plans, leading to insecurity about meeting future obligations.

I could go on, but you get the idea.

The Fed Will Intervene

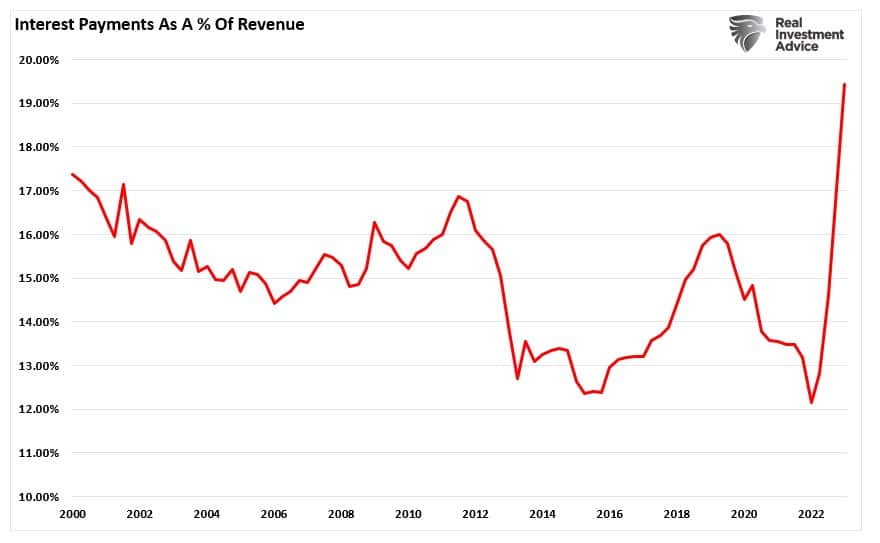

The issue of rising borrowing costs spreads through the entire financial ecosystem like a virus. Such is why the Federal Reserve and the Government will force rates lower through both monetary and fiscal policies. Such is particularly true when the interest on the existing debt absorbs nearly 1/5th of your collected tax revenues.

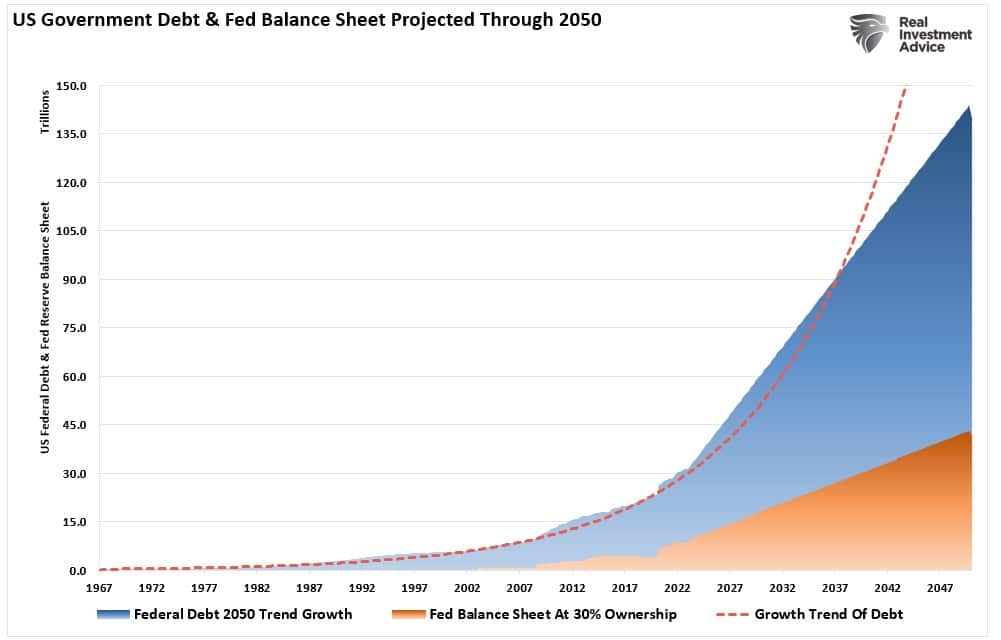

The biggest problem with the “rates must go higher” thesis is the inability of the economy to sustain higher rates due to mounting debt issuance and rising deficits. The Congressional Budget Office recently updated its debt trajectory over the next 30 years.

The chart below models that analysis using the growth trend of debt but also factors in the need for the Federal Reserve to monetize nearly 30% of that issuance.

At the current growth rate, the Federal debt load will climb from $32 trillion to roughly $140 trillion by 2050. Concurrently, assuming the Fed continues monetizing 30% of debt issuance, its balance sheet will swell to more than $40 trillion.

Let that sink in for a minute.

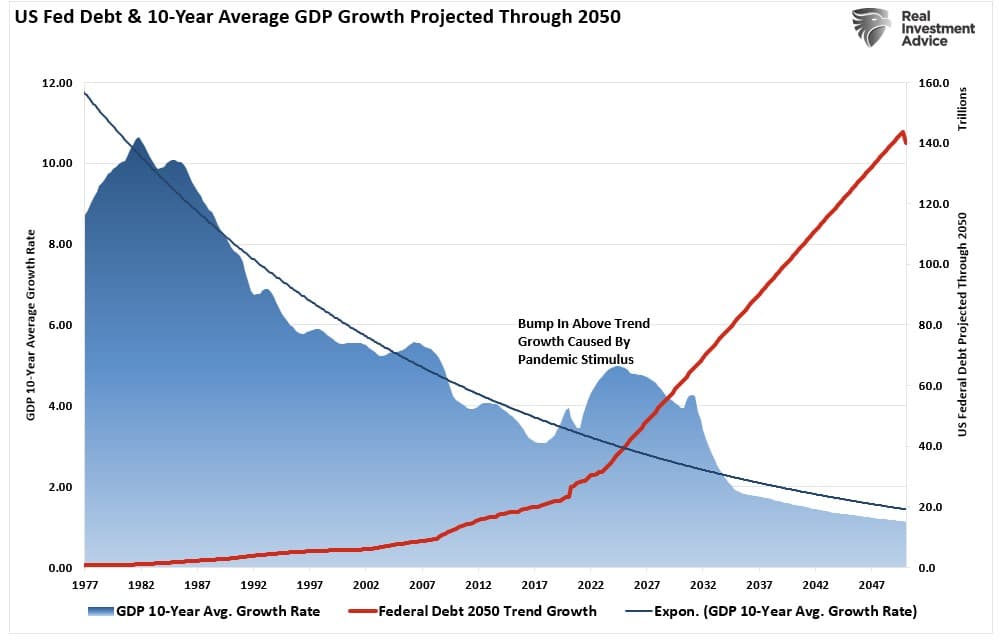

What should not surprise you is that non-productive debt does not create economic growth. Since 1977, the 10-year average GDP growth rate has steadily declined as debt increased.

Thus, using the historical growth trend of GDP, the increase in debt will lead to slower economic growth rates in the future.

Conclusion

Therefore, as debt and deficits increase, Central Banks will be forced to suppress interest rates to keep borrowing costs down to sustain weak economic growth rates. The problem with the assumption that rates MUST go higher is three-fold:

- All interest rates are relative. The assumption that rates in the U.S. are about to spike higher is likely wrong. Higher yields in U.S. debt attract flows of capital from countries with low to negative yields, which pushes rates lower in the U.S. Given the current push by Central Banks globally to suppress interest rates to keep nascent economic growth going, an eventual zero-yield on U.S. debt is not unrealistic.

- The coming budget deficit balloon. Given Washington’s lack of fiscal policy controls and promises of continued largesse, the budget deficit is set to swell above $2 Trillion in coming years. This will require more government bond issuance to fund future expenditures, which will be magnified during the next recessionary spat as tax revenue falls.

- Central Banks will continue to buy bonds to maintain the current status quo but will become more aggressive buyers during the next recession. The next QE program by the Fed to offset the next economic downturn will likely be $4 Trillion or more, pushing the 10-year yield toward zero.

If you need a road map of how this ends with lower rates, look at Japan.

Policy analyst Michele Wucker described this sort of problem in her 2016 book “The Gray Rhino,” which was an English-language bestseller in China. Unlike an out-of-the-blue crisis dubbed a “black swan,” a gray rhino is a probable event with plenty of warnings and evidence that is ignored until it is too late.

Add the debt to that list.