The mouthwatering roster of unicorn companies—privately held start-up businesses with valuations over $1 billion—that were slated to go public in 2019 led many to believe this was going to be the greatest year for initial public offerings (IPOs) since 1999. Uber, Lyft and WeWork were arguably the most anticipated of those unicorns which also included Pinterest (NYSE:PINS), Levi Strauss (NYSE:LEVI) and Cloudflare (NYSE:NET).

But as 2019 begins to wind down, something has clearly gone wrong for many of these unicorns. Almost none have delivered for investors.

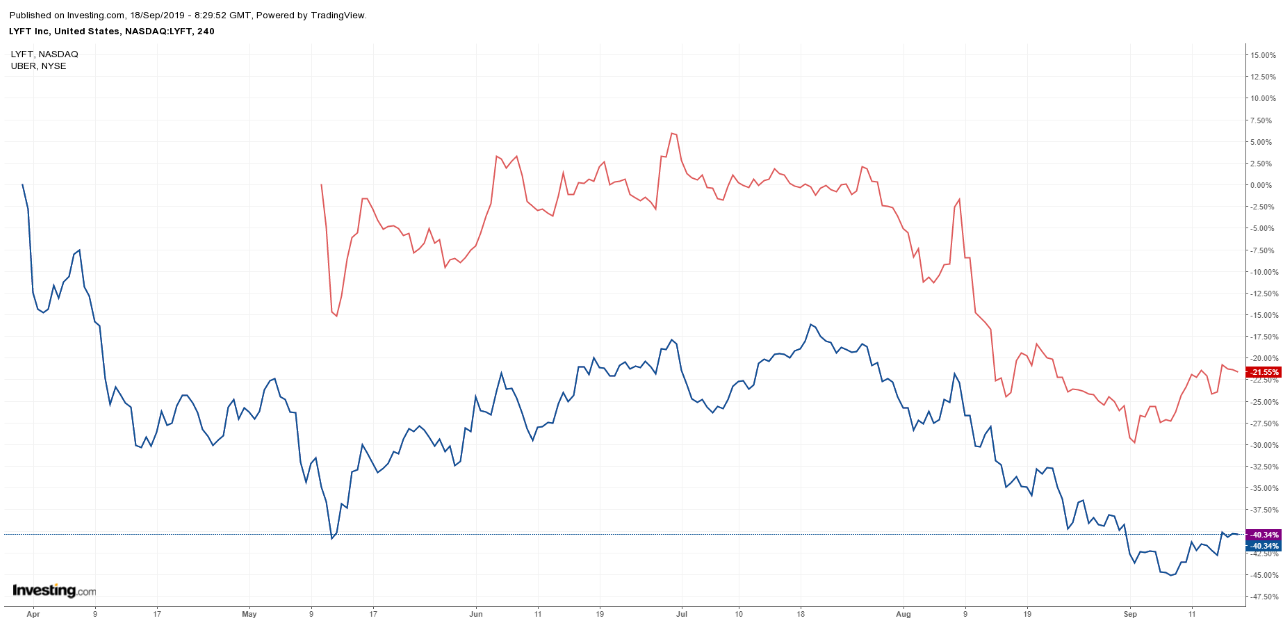

Just four months after its IPO, ride hailing giant Uber Technologies (NYSE:UBER), which once sought a $120B valuation, is trading at $34.29 per share, giving it a market cap of less than half that amount. LYFT (NASDAQ:LYFT), which aimed for a $24B valuation ahead of its IPO, currently trades at $48.06, for a market capitalization of $14 billion, down 41% from its initial pricing.

And as we write this, WeWork has postponed their roadshow, and the IPO date—which was originally supposed to occur in September—has been delayed because of tepid investor demand. A statement released by the company, as reported by the Wall Street Journal yesterday, said:

"The We Company [WeWork's parent] is looking forward to our upcoming IPO, which we expect to be completed by the end of the year."

As well, "in recent days its executives and underwriters had become resigned to something closer to between $15 billion and $20 billion or possibly lower, people familiar with the matter said." The company's valuation, which as of the last round of private funding was said to be $47 billion, continues to sink, a result of corporate irregularities and inconsistencies that will likely pesist in undermining the offering and its market cap.

What's causing the discrepancy and disappointing investors? We believe it's the drastic imbalance between expectations within private and public markets.

Business Losses and Profitability

When it comes to tolerance for revenue losses and the lack of a distinct path to profitability, private and public markets are significantly different. Of course, all start ups begin as privately held entities and many don't and never will turn a profit.

That's why venture capital funds operate the way they do: they tend to invest in multiple tens of companies, anticipating that the three to five that eventually succeed will cover the losses of the many others that failed. As well, it's common in private equity markets for early stage companies to operate at a loss, with additional funding raised by another round of investment from either new or existing stakeholders, often at higher valuations since the sole focus is on growth.

Public markets have more conservative standards. Though high-growth is appreciated, investors expect publicly traded companies to be more mature, with some key questions already answered: will this company ever be profitable? And if so, when and how much cash will it take to get to profitability?

It's telling that of the three companies focused on here, not a single one can answer those questions, even after two have already gone public. Still, the different public versus private approaches to business models is only partially to blame.

Positive Feedback Loop

When a company is privately held, management only has to interact with a limited number of stakeholders. WeWork, which leases and rents shared office space, for example, has mostly been dealing with Japanese investment entity SoftBank, which has already put $2 billion USD into the startup. Convincing a room full of people at SoftBank about the prospects of WeWork is simpler than withstanding the scrutiny of millions of investors.

Acquiring a stake in a privately-held company is hard—owners have to be willing to sell a piece of their business and for stakeholders, liquidity is limited. Naturally, all new stakeholders are bullish on the company. Dissenting voices wouldn't be rewarded with a piece of the operation.

This creates a positive feedback loop that helps fuel higher valuations whether they're realistic or not. Public markets are far less gullible...most of the time.

Continually Pushing For More

Before a company goes public, stakeholders who got in during final funding rounds see the public offering as a way to profit, but only if the public shares are valued at more than their private stake is worth. That's how WeWork's impending IPO valuation first became so outrageous. Its private investors, along with underwriter Goldman Sachs (NYSE:GS), earlier this year, pitched a valuation of $65 billion dollars. Blinded by greed, no one involved bothered to take a hard look at the company's actual fundamentals.

Uber’s $120 billion pre-IPO valuation followed the same pattern; ditto for Lyft. Going public with a fancy valuation is great, but offering shares at what is an objectively outrageous valuation is something completely different. These attempts at extracting preposterous sums of money from public markets led to an investor and media backlash on a scale seldom seen before. Hundreds of articles criticized those IPOs, leading to investors turning sour on a variety of overvalued offerings, including WeWork's.

Once it dawned on investors these companies intended to abuse public markets, there was no going back—or in the case of WeWork, additional difficulty going forward with a problematic IPO.

Lessons Learned

For companies considering an IPO, going public isn't a miracle exit into a wealthy future if your offering doesn't at the very least include a sustainable business model. If it doesn't, at least aim for a reasonable valuation so the company's flaws have some chance of flying under the radar of increasingly critical investors.

For retail investors who think getting in at a company's IPO is a sure path to riches, don't be seduced by fancy marketing and lofty private valuations. They don’t mean much once a company's shares hit the public trading floor. When a company goes public conditions change. Instead of its valuation steadily increasing, it can just as easily go into free-fall.