(Bloomberg) -- The possible return of La Nina threatens to give the drought-ravaged U.S. West another winter without much rain or snow.

The U.S. Climate Prediction Center issued a watch for La Nina on Thursday, saying there’s a 66% chance the phenomenon will return for a second straight year some time in the November-January period. La Nina occurs when the equatorial Pacific Ocean cools, triggering an atmospheric chain reaction that can cause droughts across the western U.S. and roil weather systems globally.

“What concerns us is that the models are really starting to pivot and when the models start to pivot in the June, July, and August time frame we really start to pay attention,” said Michelle L’Heureux, a climate scientist at the center. “There is a two-in-three chance at its peak, but there is still a one-in-three chance it won’t form which is why it is called a watch.”

Back-to-back La Ninas aren’t rare -- they’ve happened eight times since 1950 -- but it would come at a time when much of the U.S. West is already battling catastrophic dryness that’s seared crops, strained power grids and sparked widespread wildfires. California relies on winter storms for most of its water and those systems are usually deflected northward during a La Nina.

A full third of California is gripped by the most severe category of drought, according to the U.S. Drought Monitor. A winter without rain and snow would make that worse.

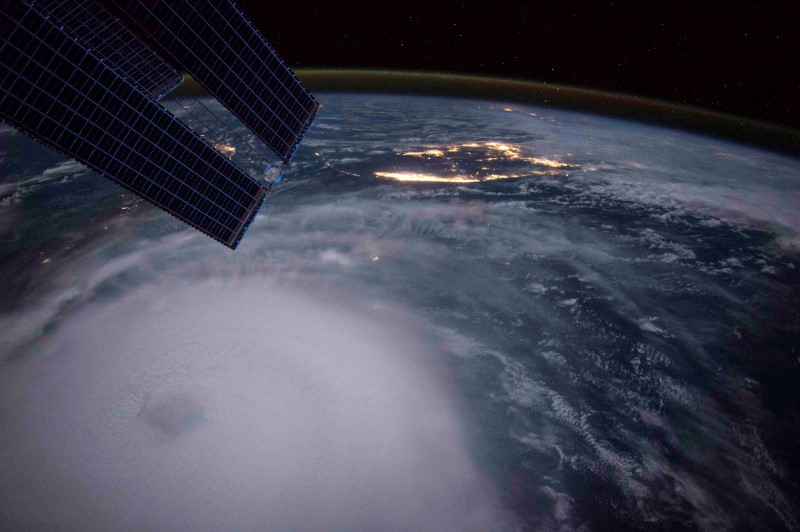

The consequences of La Nina go beyond the U.S. As odds for the pattern rise, the chances decline for an El Nino, which would remove an impediment to hurricanes forming in the Atlantic as the peak time for storms arrives in August and September. A year ago, neutral conditions across the Pacific through the first part of hurricane season and a La Nina in the final months were in part responsible for a record 30 named storms across the Atlantic, with an all-time high of 12 strikes on the U.S.

In South America, La Nina can bring more rain across northern Brazil and drought to soybean-growing areas in the south. Heavy rains across Malaysia can interfere with harvesting palm oil. Northern Australia coal-mining regions are also often hit with flooding rains.

©2021 Bloomberg L.P.