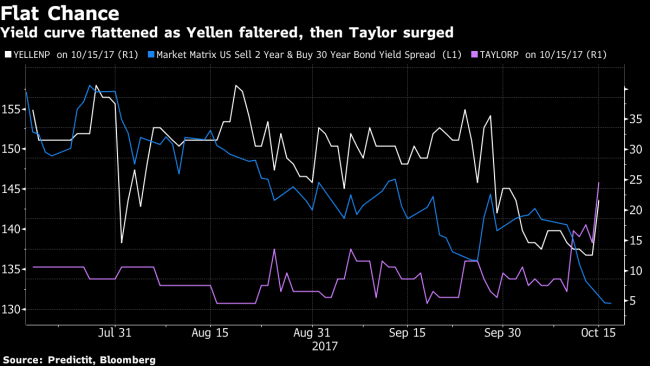

(Bloomberg) -- Investors are still betting a Federal Reserve run by economist John Taylor would mean higher U.S. interest rates despite his signaling he would be more flexible in setting monetary policy than his academic work suggests.

Reflecting such suspicion, the dollar rose and the 10-year U.S. Treasury note fell on Monday after Bloomberg News reported Taylor, a professor at Stanford University, impressed President Donald Trump in a recent White House interview.

Driving those trades was speculation that the 70 year-old Taylor would push rates up to higher levels than a Fed helmed by its current chair, Janet Yellen. That’s because he is the architect of the Taylor Rule, a tool widely used among policy makers as a guide for setting rates since he developed it in the early 1990s.

In a sign of pragmatism that may have been aimed at Trump, Taylor said on Friday his support of a rules-based monetary policy isn’t an argument for overly constraining central bankers in setting rates. His remarks, two days after he sat down with the president, also indicated a willingness to adjust a key input in his theory. And even if he did pursue tighter monetary policy there’s no guarantee he could rally fellow policy makers behind him.

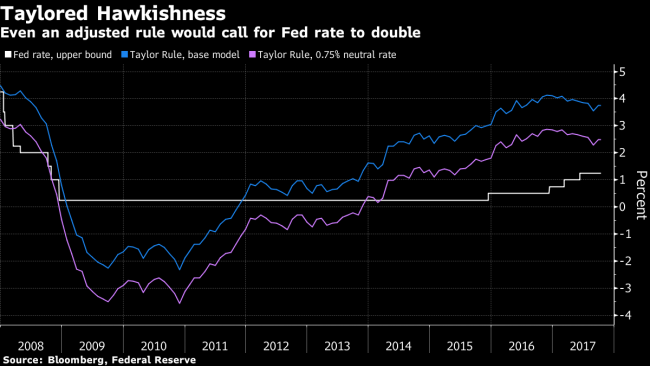

But a closer look at the rule that helped make him famous shows plenty of reasons for investors to expect a higher Fed rate going forward, even if its author is willing to adapt his guidelines to take into account recent policy-maker estimates of the so-called neutral interest rate.

That goes a ways to explaining why Fed fund futures started pricing in a more aggressive tightening cycle over the past week as speculation grew that Trump would pick Taylor as Chair.

Longer-term yields -- strongly influenced by growth and inflation expectations -- have also moved closer to short-term yields tied to monetary policy expectations as investors bet the Fed will be more willing to risk sparking a recession than it has been of late.

If used as it was originally proposed, the Taylor Rule would imply that the Fed rate -- currently set at a range of 1 to 1.25 percent -- needs to be at 3.75 percent in order to meet the central bank’s goals of maximum employment and 2 percent inflation. Even if Taylor shied from pushing rates to that level as Fed Chair, using the rule would still make him appear much more hawkish than his two predecessors.

Taylor has criticized rates in the U.S. and elsewhere as far too low in recent years, a position that has been embraced by some Republican lawmakers.

Last week, he released a paper floating the idea that the inputs to his rule could be tweaked. He mentioned the real interest rate -- which is adjusted for inflation -- that would be needed to maintain stable growth. That rate has long been set at 2 percent, but recent Fed minutes have indicated policy makers see the rate around 0.75 percent right now.

While feeding that into Taylor’s model provides a lower output, it still looks like he would be much more hawkishly inclined when it comes to monetary policy.

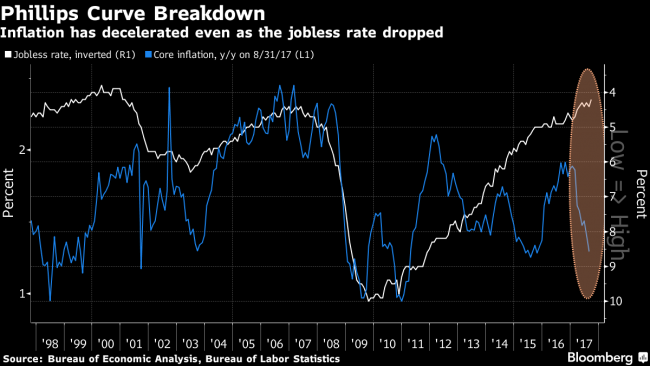

Another key input for the Taylor Rule is assuming that a jobless rate of less than 5 percent will spur inflation. That’s cast doubt over the reliability of the so-called Phillips Curve, which asserts an inverse relationship between price pressures and joblessness. But it’s been about two years since unemployment has been above 5 percent and more than five years since core inflation topped the Fed’s 2 percent target.

That 5 percent figure for the non-accelerating inflation rate of unemployment is still questionable. Inputting a value closer to 4 percent -- to account for the fact that even the current rate of 4.2 percent isn’t resulting in quickening inflation -- makes the Taylor Rule’s recommendation looks a lot more like the Fed’s past settings, and its forward guidance.

Boston Fed chief Eric Rosengren isn’t worries about Taylor: read more here.