By Linda Sieg

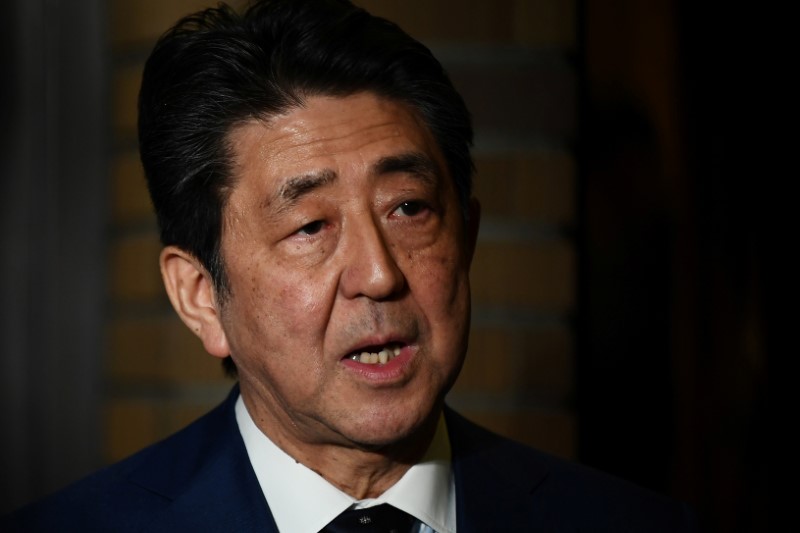

TOKYO (Reuters) - Postponing the Olympics due to the coronavirus pandemic has turned a hoped-for year of triumphant celebration for Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe into a struggle to stem the outbreak and save the economy, but is unlikely to cost him his job.

Abe, who returned to office in 2012 promising "Japan is back", has closely associated himself with the multi-billion dollar Games. He promised the Fukushima nuclear crisis was "under control" during Tokyo's bid and appeared as video game character Super Mario at the 2016 Olympics closing ceremony.

Hosting the Games has been part of Abe's campaign to lure more foreign tourists to Japan as a pillar of economic growth. It would also achieve a goal that eluded his beloved grandfather Nobusuke Kishi, who was prime minister when Tokyo won its bid for the 1964 Olympics but resigned before event.

Now, the global spread of the virus has scuppered rosy scenarios in which Abe would preside over the Games this year, setting the stage to lead his party to an election victory.

After a call with International Olympic Committee (IOC) president Thomas Bach, Abe said on Tuesday the July 24-Aug. 9 event would be rescheduled for the summer of 2021 at the latest.

Postponing the Games - rather than cancelling them - could help Abe keep his job, given a weak, fragmented opposition, the absence of consensus in his ruling party about a successor, and voter acceptance of the need for delay.

"Cancellation means no Tokyo Olympics. That is not something Japanese citizens want to see," said former diplomat Kunihiko Miyake, now research director at the Canon Institute for Global Studies, speaking before Abe's announcement. "If they are postponed, there is still hope."

POLITICAL SURVIVOR

Abe has survived several scandals to become Japan's longest serving prime minister, but came under fire for his response to the outbreak, first for a perceived lack of leadership and later for abrupt steps including school closures.

Since then, he has promised measures to counter the impact on an economy that was already teetering on the verge of recession, and his voter ratings have recovered. A mid-March Kyodo news agency survey showed his approval rating had risen to 49.7 percent, up from 41.0 percent in February.

"Abe's willingness to accept a delay, which would have once been an unthinkable political defeat ... could even give him a boost, as polls have shown that strong majorities favoring delaying the games," wrote Tobias Harris, senior vice president at consultancy Teneo.

Though it was one of the first places outside China to be affected by the new coronavirus, Japan has since reported fewer confirmed cases than the United States and some big countries in Europe. But critics say that is at least partly because it has been testing fewer people and the outbreak could yet become widespread, overburdening hospitals.

The economy was at risk of slipping into recession before outbreak hit and cancelling the games will be a further blow to household and corporate sentiment, already souring from event cancellations, slumping tourism and travel curbs.

"If the economy tanks just about when he is going to leave office, what does that do to his Abenomics legacy?" said Columbia University emeritus professor Gerry Curtis, referring to the Abe's hallmark mix of easy money, spending and reforms.

(reporting by Linda Sieg; Editing by Alex Richardson)