By Geoffrey Smith

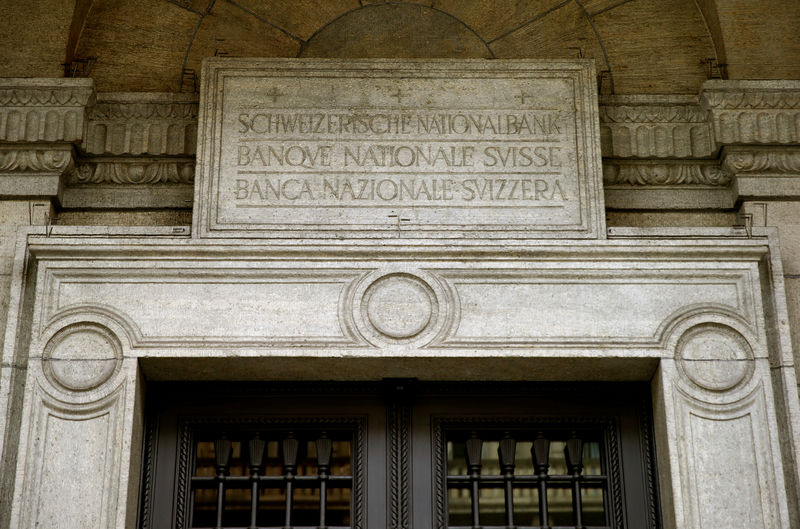

Investing.com -- Switzerland's central bank said on Monday it made a loss of 142 billion Swiss francs ($141 billion) in the first nine months of the year, as the franc's appreciation and the sharp rise in global interest rates hurt the valuation of its huge asset portfolios.

The number is another powerful illustration of the shockwaves that the U.S. Federal Reserve's tightening of monetary policy has sent through financial markets this year. While the Swiss National Bank cannot go bankrupt as long as there is demand for Swiss francs, its accounting results pose some awkward questions for an institution widely held to be among the most conservative in global finance.

The loss was almost entirely due to the bank's foreign asset holdings, which - in contrast to the holdings of other central banks - are partially invested in private securities, including equities. Some 71 billion francs of the loss was attributable to its bond holdings, while its equity holdings lost 54 billion francs. The paper losses for the bond portfolio are, however, a poor reflection of the portfolio's credit risks, given that over 95% of it is rated single-A or higher.

While equities account for only 25% of the SNB's foreign assets, they accounted for nearly 40% of the recorded loss. The SNB's equity holdings are all passively managed and reflect a broad range of advanced and emerging market indices.

The rest of the loss was accounted for by foreign exchange mark-to-markets.

The SNB holds equal proportions of its FX reserves in both dollars and euros - 38% in each. While the dollar portion of the portfolio has gained around 10% this year, the euro portion has lost just under 5%. Smaller allocations to sterling and the Japanese yen have fared considerably worse.

The SNB has accumulated a massive balance sheet over the last decade through constant interventions to depress the franc's exchange rate and keep the Swiss industry competitive with the rest of the world. At 889 billion francs, the SNB's total balance sheet is now nearly 120% of GDP.

It has had a particularly long and bitter struggle with the euro, whose persistent weakness - accentuated this year - has allowed neighboring Italy, Austria, Germany and France to gain a competitive advantage vis-a-vis Swiss producers.