By Geoffrey Smith

Investing.com -- You can argue about whether or not you’re in a recession (if you really have nothing better to do), but there’s no arguing that the world is in a rare and extreme synchronized growth slowdown.

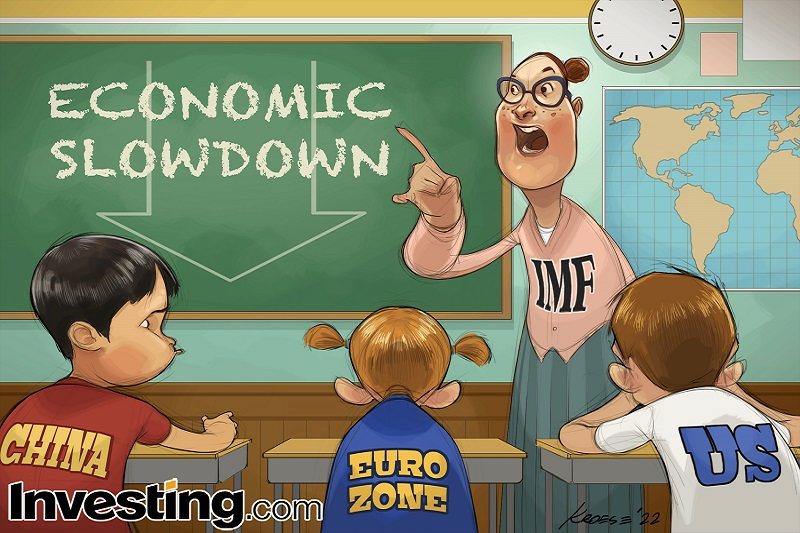

The three areas that account for nearly 60% of global economic output – the U.S., China and Europe – are all losing momentum, a point drummed home with typical undertaker-like sobriety by the International Monetary Fund last week as it cut its growth forecasts for the next 18 months yet again.

True, the IMF’s forecasts have a reputation of being so far behind the rest of the market that they act as a reverse indicator: The time to go bullish is when the IMF is at its most bearish, so the logic goes.

And U.S. investors, at least, seem to have taken that lesson to heart last week, with a ripping rally in U.S. stocks. Copper, too, has bounced vigorously in the last two weeks, suggesting that Chinese investors also want to believe that the worst is behind them.

But is that really the case?

Each of those regions has a particular problem to deal with. And in none of those cases has the underlying cause of that problem been dealt with.

In the U.S., the Federal Reserve continues to tighten monetary policy. While a growing number of indicators - not least the June Job Openings survey released on Tuesday - support the argument that tightening is having the desired effect on the housing and labor markets in particular, inflation itself remains sticky. Sequential monthly price increases have remained strong, and gains in average hourly earnings remain solid. The shortage of labor in many sectors of the economy remains acute, ensuring that workers’ bargaining power is higher than in much of recent history.

In Europe, meanwhile, there is no end in sight to Russia’s war in Ukraine that has turned the region’s energy policy (if it can be called that) on its head. Germany, its biggest economy, faces a very real threat of gas rationing and recession as the year drags on.

In China, the rebound that accompanied the end of Shanghai’s lockdown in the spring looks increasingly like a false dawn. Global demand for Chinese goods is cooling as inflation forces consumers to focus on the essentials such as heating and food. The government still appears to have no plan for moving China to a state of living with Covid-19 and, more importantly, has still not resolved the chronic real estate crisis in any meaningful way.

Indeed, the latest news out of China suggests that the authorities either can’t or won’t take more radical action. The People’s Bank of China’s decision last week to release just enough funds to take the heat out of a buyers’ payment boycott was a case in point: the authorities will do just enough to nip popular unrest in the bud, but have no roadmap for clearing up the balance sheet of a desperately over-extended sector. Evergrande, the largest of China’s troubled developers, missed a deadline to present a restructuring plan last week, despite having had nearly a year to put one together. Meanwhile, its more liquid assets appear to be being plundered by creditors with privileged status – something that led to the resignation of Evergrande’s CEO and CFO last month.

No wonder, then, that the IMF concluded that “the risks to the outlook are overwhelmingly tilted to the downside.

“The war in Ukraine could lead to a sudden stop of European gas imports from Russia; inflation could be harder to bring down than anticipated either if labor markets are tighter than expected or inflation expectations unanchor; tighter global financial conditions could induce debt distress in emerging market and developing economies; renewed COVID-19 outbreaks and lockdowns as well as a further escalation of the property sector crisis might further suppress Chinese growth; and geopolitical fragmentation could impede global trade and cooperation.”

The combination of supply-side and demand-driven inflation is still very real, and nowhere is there conclusive evidence of it ending yet. Against that background, going all in on a bullish pivot in markets seems, to say the least, premature.