By Jessie Pang

HONG KONG (Reuters) - Hong Kong's government review of public broadcaster RTHK has found deficiencies in editorial management and a lack of transparency in handling complaints, signalling a major overhaul of the revered institution as concerns grow over media freedom.

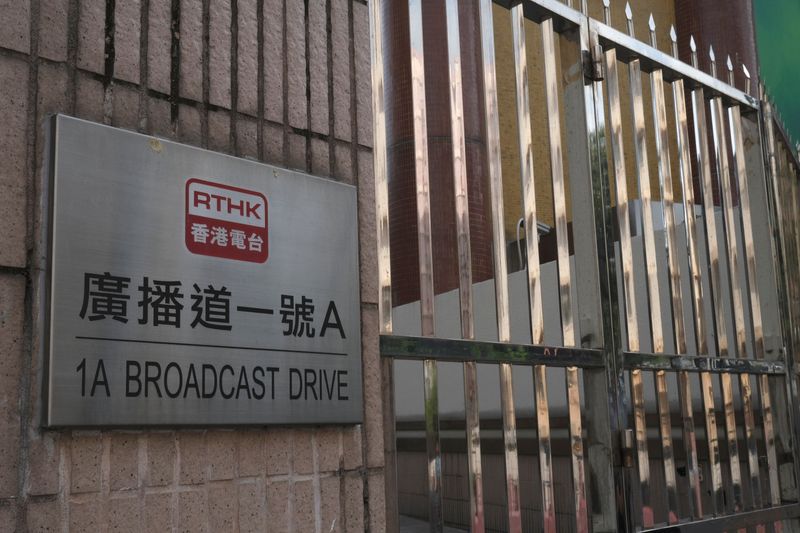

The only independent, publicly funded media outlet on Chinese soil, Radio Television Hong Kong was founded in 1928 and is sometimes compared to the British Broadcasting Corporation. Its charter guarantees it editorial independence.

It angered Hong Kong's government, the police, and Beijing with its coverage of 2019 anti-government protests that shook the Asian financial hub, including several investigations that sparked widespread criticism of authorities.

"There are deficiencies in (the) editorial management mechanism," the Commerce Bureau said in a 154-page report of its review released on Friday.

There were "no well-defined and properly documented editorial processes and decisions," and no "clear allocation of roles and responsibilities among editorial staff," it added. "Weak editorial accountability is observed."

The government-led review focusing on aspects of RTHK’s governance and management was announced last year, spanning the issues of administration, financial control and manpower.

However, the union of the broadcaster's staff said the review "challenges the bottom line of logic".

In a statement, it added, "Editorial autonomy has vanished into nothing."

Earlier on Friday, Hong Kong appointed deputy secretary for Home Affairs Patrick Li as director of broadcasting, from March 1.

Li, a career bureaucrat who worked in the government's constitutional and mainland affairs and security bureaus, but has no experience in media, will replace veteran journalist Leung Ka-wing, six months before his contract expires.

Leung, whose management the review has described as too "passive", was not thanked for his service in the government notice of the new appointment, contrary to practice. Beijing has said patriots must run every public institution in Hong Kong.

The broadcaster "serves residents of the city instead of bureaucrats," its staff union said.

"It’s a whole body operation," said Bruce Lui, a former host of RTHK's 'China on the dot' radio programme.

"It’s foreseeable that sensitive reporting that, for example, might involve criticising China's Communist Party will be hard to do," added Lui, who is now a journalism lecturer at Hong Kong Baptist University.

Pro-Beijing supporters regularly file complaints against RTHK and stage protests outside its headquarters, accusing it of anti-government bias.

Last week, RTHK said it was suspending the relay of BBC radio news after China barred the BBC World News service from its networks, highlighting how media in the former British colony are falling under Beijing's tightening sway.

When Beijing expelled about a dozen journalists working for U.S. news outlets last year, it also barred them from relocating to Hong Kong, which returned to Chinese rule in 1997.

Critics see a sweeping national security law imposed by Beijing in June 2020 as a blunt tool to stifle dissent and curb media freedom and other liberties. The law calls for tougher media regulation and supervision.

The government says rights and freedoms remain intact.

Since the law was introduced, most prominent pro-democracy activists and politicians have been arrested, while some songs and slogans have been banned, along with anything that may be considered political activity in schools.

Media tycoon and Beijing critic Jimmy Lai, the founder of the popular Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL) Daily tabloid, is the highest profile activist charged under the new law, accused of colluding with foreign forces.

Hong Kong's ranking fell to 80 in the global press freedom index of Reporters Without Borders in 2020, from 18 in 2002. China ranks 177th.