Canada’s Consumer Price Index - supposedly our best benchmark of inflation - is at 4.7%, far above target levels of 2% and the worst it’s been in two decades. Unfortunately, actual inflation is much higher. While it’s difficult to find a consensus or definition for what “actual” inflation is, certain numbers highlight gaps in the Statistics Canada methodology for calculating CPI. For example, StatCan does not track used vehicle prices, a major indicator of inflationary pressure, which in 2021 jumped by 38% in Canada compared to 31% in the U.S. Another example is the price of food. According to StatCan, food prices are up 2.7% over the past 12 months, whilst independent research, such as Dalhousie University’s Agri-Food Analytics, show estimates closer to 5%. And then, of course, there’s the elephant in the room: Canadian real estate. The StatCan approach does not price in the expected appreciation of owner-occupied dwellings, making it hardly reflective of hot housing prices across Canada, which as of November 2021 are up an average of 20% from the previous year.

Despite rate hikes widely expected as early as Jan 26, and some analysts expecting as many as 5 rate hikes by the end of 2022, inflation is unlikely to normalize this year. The price of key goods will continue to rise: energy will become more expensive for Canadian consumers. That’s a separate article (this one in fact), but Europe is the obvious canary in the coal mine. Food inflation is also likely to worsen, as fertilizer prices continue to rise, driven in part by rising energy costs. Prices for both new and used cars are also unlikely to normalize, with the chip shortage set to drag on for yet another year. The growth in house prices, however, provides a somewhat more mixed picture. The meteoric rise of real estate is predicted to slow this year, rising “only” 10% - half the increase seen in 2021, but still significant for what is already the most expensive and least affordable real estate in the G7.

Who’s to blame for housing prices? BoC: Not My Circus, Not My Monetary Problem

Tiff Macklem, the BOC governor, has blamed the rising cost of goods on a variety of factors apart ranging from the supply chain crisis and excess demand during the reopening trade, to the cost of energy and the price of housing, almost as though overstimulated demand were divorced from excessive liquidity. In short, Macklem and other central bank governors have blamed inflation on everything except monetary policy. Whilst acknowledging that the rise in property prices is a result of a long, but supposedly necessary period of low-interest rates, Macklem blames the problem on supply constraints and investors. He also strongly disavows responsibility for fixing the situation, calling housing prices “not really a monetary policy problem” and places the responsibility instead on government policies, which he believes are better suited than monetary policy for addressing the situation. This is only partially true.

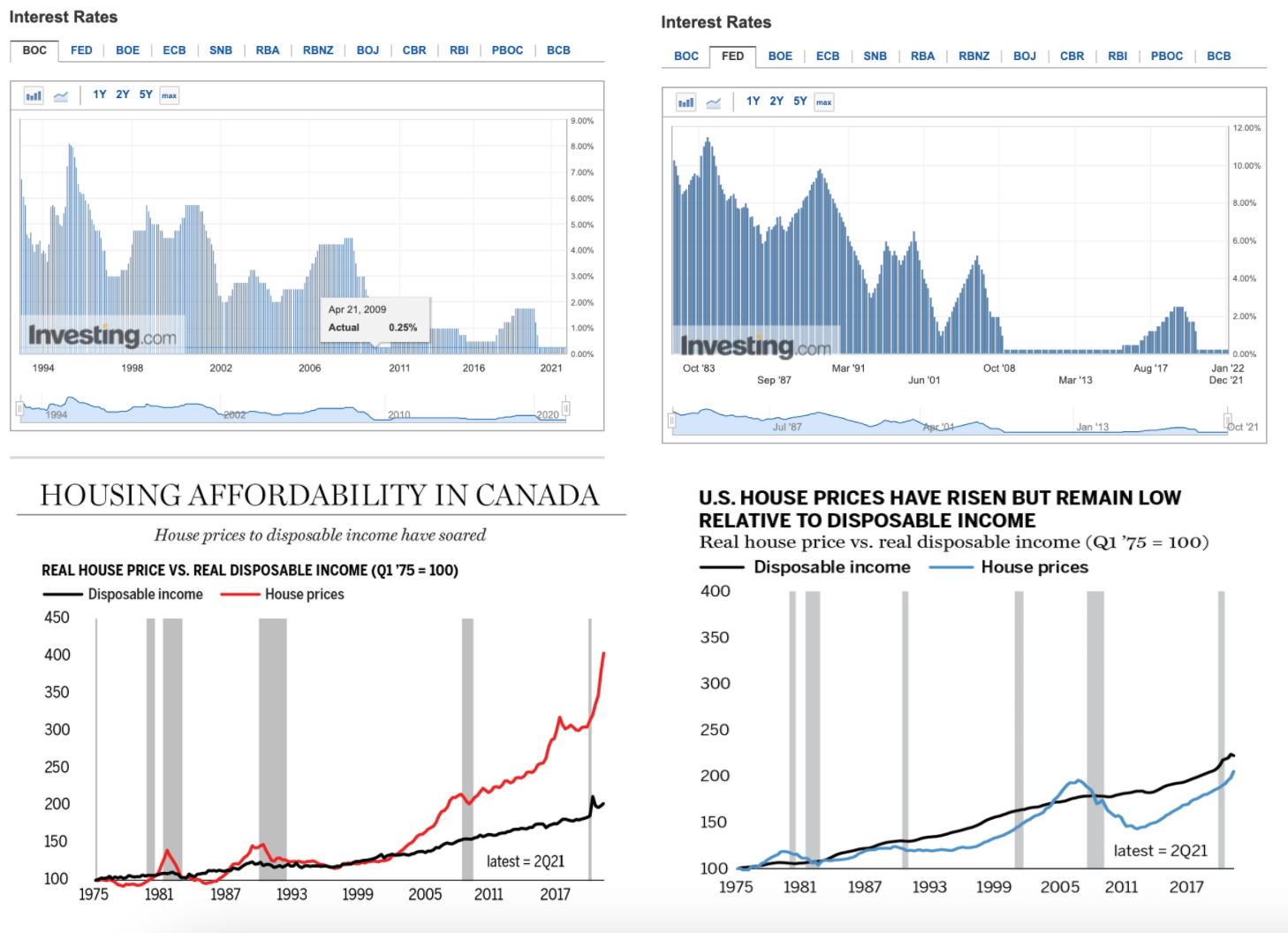

A low-interest-rate environment post-2008 has certainly contributed to housing prices by overstimulating the investor activity Macklem blames, particularly from much-maligned multi-property owners (who now make up 25% of real estate transactions). The low-interest-rate environment is also certainly to blame for Canadians overleveraged on housing, which has led to levels of household - primarily mortgage - debt that now exceed the value of the country's Gross Domestic Product (GDP). But interest rates are only part of the problem. While Canada and the United States have operated in similar low-interest-rate environments since the 2008 crash, housing in the United States hasn't seen nearly the same level of frenzied activity, growth, and overvaluation as the Canadian market.

If not interest rates, what has caused Canada’s housing crisis?

Apart from the oft-cited supply problem and investor activity, Canadian housing market prices remain highly sensitive to international demand: a contentious argument but one that is clear when looking beyond the top-line numbers. Whilst StatCan pegs the rate of non-resident ownership at only around 4.2% the Vancouver market and 3.8% of the Toronto market, this data is collected based on property transfer data when monetary penalties or taxes are involved, which incentivizes under-reporting and the creation of alternative structures to bypass regulation. And there’s another important caveat that makes StatCan numbers even murkier. By and large, Canada does not track the foreign ownership of companies, structures that are often used to circumnavigate the foreign buyer tax. These factors, as well as the inability to track the estimated $131 billion of money laundered through ventures in Canada, primarily real estate, have led to generally under-reported levels of foreign capital in Canadian real estate.

However, even the numbers available are damning if one dives a little deeper than the reportedly low rates of foreign ownership. Even as per the property transfer data available to Statistics Canada, the values of property owned by non-resident owners are significantly higher. At the peak of the backlash against foreign-owned housing that led to the introduction of a 15% Non-Resident Speculation Tax in Toronto and Vancouver, the difference in values between non-resident and resident-owned housing was as much as $707,800 for single-family homes in Vancouver. In Toronto, the gap was relatively lower with non-resident single-family homes valued at $103,500 higher on average. Whether the (easily and often circumnavigated) tax worked is debatable, as it landed at the same time as Chinese capital controls and a period of higher interest rates - but more on that in a minute.

The divergence between the U.S. and Canadian real estate markets post-2008 can also partially be explained by differences in investor psychology, reinforced by the 2008 crisis, when the American housing market collapsed but the Canadian market did not suffer a similar correction. Canadians tend to consider real estate as a risk-free asset that will only appreciate. Speculative frenzy is buoyed by the perception the property bubble is in a way, too big to burst; the sense that the Canadian economy is too dependent on housing for collapse to be an alternative, and that monetary or government policy would actively prevent the collapse of the Canadian housing market. This sense may be more than investor instinct, however. It may well be the truth.

Is Canadian housing too big to fail?

Currently, more than 10% of Canada’s Gross Domestic Product is derived from residential real estate activity. The total value of the housing sector is estimated to be over 300% of the country's GDP. An excellent article by Daniel LeCalle, in the context of the Evergrande crisis, points out that:

“No economy has been able to ignore a property bubble and even less so offset it and continue to grow, replacing the bust of the real estate sector with other parts of the economy…. Heavily regulated economies from Iceland to Spain have failed to contain the negative impact of a real estate sector collapse".

Although in these examples the average size of the sector was closer to 15-20% of the country’s GDP, the consideration isn’t whether the Canadian housing market is too big to fail. The far more important question is whether the Bank of Canada believes the Canadian housing market is too big to fail. And that’s an easy one to answer.

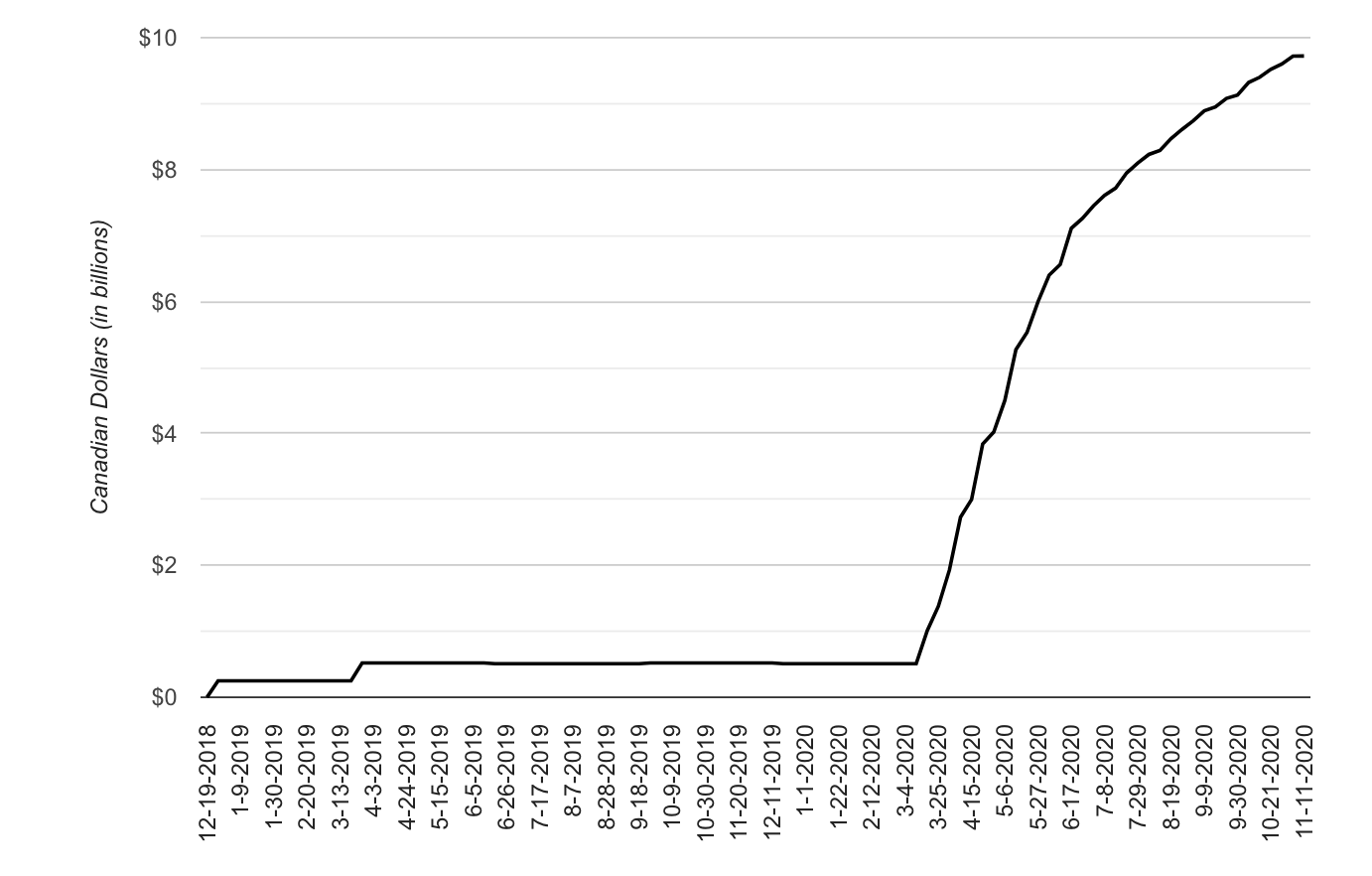

The Bank of Canada would certainly seek to stave off a decline in housing prices in order to protect overleveraged Canadians and the real-estate reliant economy. In early 2020, when the impact of the pandemic on Canadian real estate was not yet entirely clear the Bank of Canada began purchasing billions’ worth of Canadian Mortgage bonds, injecting the mortgage market with liquidity to lower mortgage rates even further and stave off a potential pandemic-driven downturn in housing. Between March 2020 and the end of October 2020, the bank of Canada purchased $9.601 billion worth of Canadian Mortgage Bonds - a nearly 1,750% rise from the same week the previous year. Retrospectively, the BoC’s CMB shopping spree proved either highly successful or entirely unnecessary.

The period between 2017- 2018 provides another example of the BoC’s direct intervention to prevent a downturn in housing prices through CMB purchases. In 2017, a combination of higher interest rates, Chinese capital controls, and the aforementioned 12% speculative buyer tax led to single-family homes falling ~12% in both Toronto and Vancouver. Increasingly concerned about overleveraged buyers and household debt vulnerabilities, the BoC began injecting millions into mortgage liquidity through the purchase of Canadian Mortgage bonds, which had the effect of lowering mortgage rates, and successfully reinvigorating home sales and values in 2018.

Investor Takeaway: Is Canadian Real Estate still a solid investment?

Although the aggressive rate hikes now anticipated from BoC and the Federal Reserve (which also impacts Canadian mortgage rates) will cool speculative buying and domestic investor activity, there’s not much that monetary policy can achieve if foreign demand remains robust. While the Bank of Canada may have helped create, and has certainly at times helped artificially inflate property prices, it may be beyond its capability to now help tame the beast it helped birth.

Whilst government policy has maybe cooled housing price in the past (i.e in 2017 with the speculative buyer’s tax), the current government’s response to the issue so far is likely to be ineffective: the newly introduced 1% Underused Housing tax on the value of non-resident, non-Canadian owned residential real estate will be small game to investors who are willing to pay up to millions of dollars over asking price to move or invest their wealth into prime Canadian Real estate. If government policy were enacted to cool housing prices, it’s hard to see the BoC standing by to allow a downturn in housing and its fallout on uninsured and overleveraged Canadians, particularly as levels of household debt, and vulnerabilities have worsened since 2018 when the Central bank felt compelled to intervene and prop up the property market. The percent of uninsured and highly-leveraged mortgage holders has increased from approximately 14% in 2018 to 25 % in early 2021.

Canadian housing prices are unlikely to cool to a point where income to house price ratios return to levels similar to the U.S. or even narrow significantly. For the foreseeable future, Canadian housing will be far more expensive than comparable real estate in the U.S., and likely even more unaffordable than it already is. With little change to demand fundamentals, housing prices are unlikely to normalize. The unaffordability of housing is likely to remain a standard feature in Canada. Perhaps disheartening news for the approximately 30% of Canadians who do not own their own homes, but good news for homeowners, and still a solid opportunity for investors in Canadian real estate and REITs, many of which remain undervalued and a strong buy for 2022 despite outperforming housing growth in 2021.