The bad news is that the contraction in the money supply appears to be over. That’s not bad news per se (see below), but it’s bad in that the anti-inflationary work that was happening is coming to an end before it’s quite finished. Although I would be reluctant to annualize any one month’s change in M2, the $92bln increase in M2 in March was the largest increase since 2021.

It only annualizes to 5.5%, so it isn’t exactly running away from us – but it’s positive. The 3-month and 6-month changes are also positive, and the highest since early 2022 in each case. Again, we’re only 0.72% above the ding-dong lows of last October, but the sign is now positive.

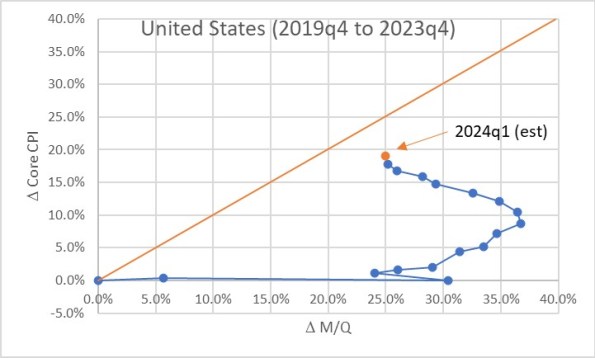

With the money supply figures now in, and with the advance Q1 GDP report due this week, we can revisit our chart of “how much more inflation ‘potential energy’ remains.” (see “this article,” November 2023). As that article (and this chart) illustrates, if M2 doesn’t go down then this gets more difficult. M2 in Q1 rose at a 1.24% annualized rate over Q4. GDP is expected to rise 2.5% annualized. So M/Q…barely moves, as the chart shows.

We will eventually get back to the line, unless velocity is permanently impaired. Despite all of the crazy people who told you it was, there’s no evidence of that. M2 velocity will rise about 1% (not annualized), if the GDP forecasts are on point. That will be the smallest q/q change in several years, and velocity will be getting very close to the 2020Q1 dropping-off point. But there frankly is no reason for velocity to stop there; higher interest rates imply higher money velocity. However, we are getting close.

(Incidentally, if you’re curious how we can be almost back to the dropping-off point of velocity and yet still be 5% below the line in the first chart above, it’s because I’m using core inflation. With food and energy, we’re a little closer to the line and have used up more of the ‘potential energy.’ But food and energy are of course volatile and so while a good spike in energy prices would look like we’ve used up all of the potential energy, that could just be a one-off effect.)

Either way, we aren’t too far away from getting back to home base and that’s good news. Yes, prices by the time we are done will have risen 25% since the end of 2019, and that can’t really be characterized as a ‘win.’ Let’s go Brandon. But we are getting closer.

The good news about the new rise in M2 is that it’s timely. Markets and the economy were starting to show signs of money getting a little tight; losing a little lubrication in the machinery. An economy does need money to run, and while the only way we can get back to the old price level is to have money supply continue to decrease, that’s also a painful process.

In the long run, we would have price stability if the change in M was approximately equal to the change in GDP. If we want 2% inflation, then we need M to grow about 2% faster than GDP. Vacillating velocity means that it isn’t purely mechanical like that – the steady decline in velocity since 1997 is the only reason that inflation stayed tame despite too-fast money growth over that period – but the long downtrend in velocity is likely finished since the long decline in rates is finished. Thus, if we get money supply growth back to the neighborhood of 4%, we can get our 2-2.5% growth with restrained inflation over time.

I am not super optimistic that all of that will work out so nice and cleanly like we draw it up on the chalkboard, but I am more optimistic about it than I was two years ago. We still have some sticky inflation ahead of us, but if the Fed keeps reducing its balance sheet then eventually we will get inflation below the sticky zone and back towards ‘target’ (even though there isn’t a target per se any more).