Headlines are shouting that the world is in the grips of a massive deflationary spiral, but you would never believe it when retail prices keep rising, especially for groceries. Yes, gasoline prices have fallen, the one undeniable example that price reductions can really happen in our inflation-programmed reality. Analysts, however, look much further back in the supply chain to what are commonly referred to as Purchasing Price Indexes (PPI) to gain a perspective on what is coming down the pipeline from the industrial source. The story they find is one of outright deflation for years in many cases, not just months.

The more astute approach, however, is to track what is happening all the way back to the raw materials themselves, and the picture that has been forming of the state of the commodity industry is not a very pretty one. The press has focused on the oil industry, but the same situation of slackening demand and over supply has prevailed in iron ore, cement, copper, precious metals, agriculture, fertilizers, and a host of other lesser known quantities that fuel the globe’s manufacturing and construction engines on a daily basis. In nearly every case, a deflationary spiral formed some time ago and continues now in search of a bottom. Each time support is found, it soon dissipates.

What are the experts saying?

The World Bank recently reduced its forecasts for oil prices and those for other key commodities for both 2015 and 2016. According to John Baffes, Senior Economist and lead author of Commodity Markets Outlook, “We see a five-year-long slide in most commodity prices continuing in the third quarter of 2015. There are sufficient inventories of oil and other commodities and demand is weak, especially for industrial commodities, which is why prices may stay persistently low.”

The slide that Mr. Baffes refers to included a 43% drop in energy prices on average in 2015. In the third quarter alone, energy and non-energy related prices fell 17% and 5%, respectively. The quarterly update on the state of the international commodity markets went on to say, “The revised forecast reflects a further slowing in global economic performance, high current oil inventories, slowing demand, notably from China, and expectations that Iranian oil exports will rise after the lifting of international sanctions.”

These continuing slides have bashed developing economies the world over from Brazil and Chile to African nations, especially those that are dependent on natural resources for their export trade. The Great Recession had already ravaged those countries that funded government operations through the development of in-ground deposits, but, as each went into overdrive to recover, the direct result was an over supply on a global scale. Inventories have increased to the breaking point, creating slack in the system.

Currency values have also deteriorated. Commodity currencies like the Aussie dollar, the New Zealand Kiwi, the Canadian loonie, and the Norwegian Krone, each one strongly correlated with the whims of commodity prices in its particular sector, went into long-term slumps. If you were fortunate to short these currencies on the down slope, then fortunes could have been made, but is there a reversal on the near-term horizon?

What ever happened to previous rosy forecasts for future commodity prices?

The forecast for commodities was not always so gloomy. After the Great Recession pullback, commodities in general began their recovery in early 2009. The ramp up was varied across the board. The prevailing story at the time was that Asian economies had bypassed the recession, including Australia and New Zealand, because four decades of outsourcing and off-shoring activities in the West had fueled double-digit economic expansions in China, India, and their neighbors. With GDP growth came prosperity and burgeoning middle classes, whose appetites tended to replicate Western consumers.

The script, which seem totally logical at the time, was that these new consumers wanted the good life – better food, better clothes, better cars, better housing, better everything. In order to meet this inexorable demand, the pressure on the globe’s commodity providers was to be excruciating. Speculators began to salivate upon hearing that “bell” and soon drove up prices for nearly every commodity, especially for Silver, well beyond any sustainable levels. The “crash”, if it can be termed that now, began in May 2011. The bottom fell out of Silver prices. Copper began a slow descent, along with others in the group. For the last year, however, drops magnified. 45% falls were not uncommon.

Is there one corporate example that reflects how dire the situation is?

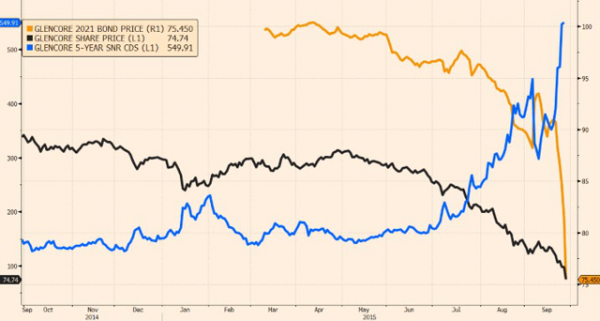

Has anyone heard of Glencore (L:GLEN) PLC? It is reputed to be the world’s largest commodity trading firm. As one analyst notes, Glencore, “if you aren't familiar, is a mining company that once was the 10th largest company in the world, based in Switzerland, with a huge commodity trading arm that makes it eerily similar to what the likes of Bear Stearns and Lehman were in the house trading craze.“ The following chart shows how quickly the market can punish a company that is highly leveraged in credit markets:

As this analyst also points out, “It's really bad when the only thing skyrocketing in your charts is the yield on your bonds and the cost of insurance contracts against your default.” Glencore’s stock price may have only fallen 17% over the period, but there is surely more carnage to come, if the other two indicators are to be believed.

In a fashion similar to Lehman Brothers and Bear Stearns of old, Glencore has borrowed up to the hilt to eke out a few basis points on its bets in the commodities market. The management team had to breathe a sigh of relief when the Fed passed on its plan to hike interest rates, but the word on the street now is that the firm is busily selling assets to shore up its balance sheet to protect its current credit rating.

In a recent CNBC article, Frank Holmes, CEO and chief investment officer at U.S. Global Investors, provided interviewers with a sanguine appraisal: “Glencore is like Lehman Brothers, they have the most sophisticated trading desk when it comes to metals, coal, copper, iron ore. They're not just a company processing ore from the ground. If it was to unravel, that could have a global impact.”

And like the hubris of Lehman Brothers, the team at Glencore likes to brag that it can make tons of money, whether markets go up or down. As the past has shown us, “up” is a lot easier and less risky than “down”. Firms like Glenmore, as well as other investment-type banks, borrow heavily in short-term markets, using their purchased assets as collateral. When a market tanks, the value of those purchased assets declines rapidly, causing immediate margin calls from the short-term fund providers. If the assets are over-the-counter with few interested buyers, then a liquidity crunch can result.

Assessing the size of the problem is also difficult. Glencore hedges much of their portfolio with exotic derivatives and arcane financial instruments, such that a large degree of the total debt load is concealed in the shadows, far from the balance sheet figures that are routinely published in the public sphere. And what bank is handling this derivative exposure? None other than Deutsche Bank (DE:DBKGn), which has come under fire for rate-fixing scandals, poor internal controls, and a derivative’s portfolio topping out at $75 trillion. Bank supporters plead that the “net” exposure is much smaller, but it is still in the major trillions, and that should be with a capital “T”.

One market commentator is not amused with the shenanigans at Germany’s largest bank. “Glencore is just a dorsal fin of a derivatives shark with Deutsche Bank being in the same pool of hot water with many giant commodities companies besides Glencore. It also is the largest lender to Volkswagon and Volkswagon's suppliers. It also has rather large exposures to emerging market currencies and related derivatives. Deutsche Bank, at $75 trillion in holdings, is the largest derivatives player in the world now. This amount of derivatives is 20X greater than the GDP of Germany.”

Is there a pending banking crisis looming in Germany and the Euro Zone?

The ECB has tried its best to generate inflation in Europe via policy commandments from on high, but to no avail. Japan has been mired in deflation since the nineties and has been blamed for exporting that malaise to Europe and elsewhere. In Asia, 9 out of 10 countries have been in a deflationary spiral for as little as a few months and for as long as over three years. China now catches the blame for being the chief exporter of deflation, but if Deutsche Bank fails, then what?

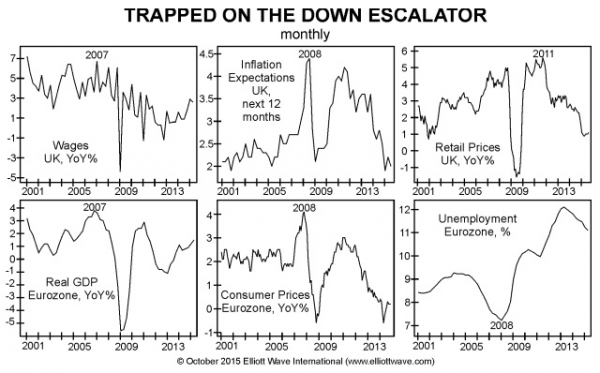

Germany has often been portrayed as Atlas, forever carrying the burden of Europe’s economic success or failure on its shoulders. The UK has also been a bellwether for the region, with France and Italy not far behind. Pundits over at Elliott Wave International have not been kind in their appraisal of Europe’s prospects, using the following diagram composite to illustrate how major economic indicators are trapped on a down escalator:

The ECB has used bank stress test data to bolster confidence in the region’s banking community, but a sudden rift in the commodities industry could very well set the dominos to falling, one after the other.

Concluding Remarks

The players in the commodity industry can be their own worst enemies. In times of over supply, they tend to ramp up the production engines in a foolhardy attempt to drive out weak members of the clan. With long-term fixed-dollar contracts to protect them, they think they can survive temporary pricing anomalies, and then eat their young, so to speak, by gobbling up new mining opportunities at fire-sale prices. We wait to see if this deflationary spiral is truly temporary in nature.

China is also a culprit. By one account, “They have used 47% more concrete in the three years between 2011 and 2013 than was used by the US over the entire 20th century! They have built now empty cities with steel, concrete, and copper with a slowdown now gripping the economy.” Demand, in this case, was illusory.

In the meantime, commodity prices continue their race to the bottom. Credit risk exposures are also expanding, and a “Glencore moment”, as transpired with Lehman and mortgage-backed securities, is a strong possibility. Can the global banking community withstand another shock of this nature? Only time will tell, but if and when it comes, shorting commodity currencies will be in vogue once more.

Risk Statement: Trading Foreign Exchange on margin carries a high level of risk and may not be suitable for all investors. The possibility exists that you could lose more than your initial deposit. The high degree of leverage can work against you as well as for you.