The heads of the Federal Reserve regional banks don’t live in Washington and are perhaps less inhibited about offering unsolicited advice to Congress.

Minneapolis Fed Chief Neel Kashkari, a former Treasury official, affirmed that the Fed will “keep our foot on the monetary policy gas” as long as needed to hit maximum employment in the wake of COVID-19, and then added some advice for lawmakers.

During an online seminar for Montana's Bureau of Business and Economic research, Kashkari said:

“And I think it’s going to be important for Congress to continue to be aggressive supporting people who have been laid off, supporting small businesses until we really get the pandemic behind us and restore the economy.”

James Bullard, president of the St. Louis Fed, urged lawmakers to do just the opposite and hold off with further aid since economic recovery looks like it will be strong without fiscal stimulus, starting even in the current quarter.

“Democrats have the power here and can do what they want,” Bullard said to reporters after a meeting at the CFA Society of St. Louis. “But the trade-off would be, in my mind—do they want to invest a lot in this recovery that already looks strong or do they want to save firepower to do other things that they might want to do?”

Bullard said people are prone to view the impact of the pandemic like the 2008-09 financial crisis. “I don’t think it’s anything like that, this shock is very different. The idea that you’re still not going to recover three, four or five years from now is not the right way to view what’s going on here,” he said.

In a virtual appearance at the Oakland University business school in Rochester, Minnesota, Chicago Fed Chief Charles Evans at least acknowledged that it wasn’t appropriate for him to advise lawmakers on a relief bill, but he insisted that even a strong economic recovery can leave some people behind and fiscal policy needs to keep up support for low-wage workers.

“I think doing more is better than doing less, in the current situation,” Evans said.

“Clearly, we have a ways to go before we get back to the vibrant economy we had on the eve of the pandemic.”

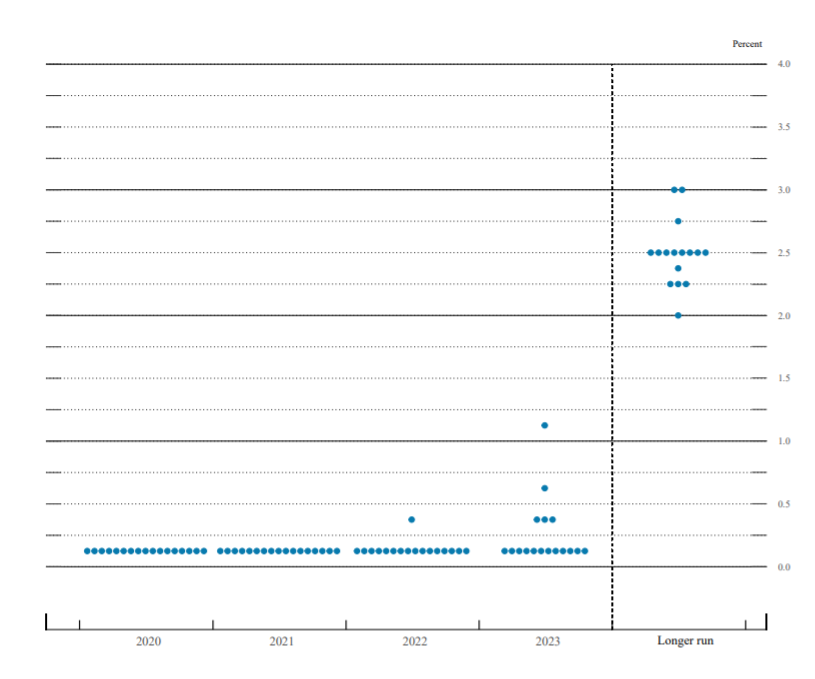

Atlanta Fed Chief Raphael Bostic is also bullish about the economy, and he expects growth will exceed expectations. He is not worried about the economy overheating this year, but he does think the Fed might have to start raising interest rates in mid-2022, some 18 months sooner than most Federal Open Market Committee members, according to the December dot-plot graph.

“This recession was unlike anything we ever had before, so the recovery is going to be that way as well,” Bostic said on CNBC. “A lot of the recent developments have been positive. We should be open to the possibility that things might happen more strongly than they would otherwise.”

Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen, the former Fed chair, convened regulators to talk about market turbulence due to the short squeeze on GameStop (NYSE:GME) shares and other surges driven by retail momentum investing. But she cautioned ahead of time that they would probably not do anything right away, and the result of the meeting was to have the Securities and Exchange Commission and other market regulators study the issue.

Cleveland Fed Chief Loretta Mester said this is the right approach. She doesn’t think Fed policy has made markets unstable, nor does she anticipate any changes in monetary policy from the market turbulence.

“You’re going to get volatility in the market from various sources,” she told a CNBC interviewer. “I don’t think this should influence what our monetary policy is.”

Like Evans, Mester wants to look at employment disparities behind the aggregate numbers.

“Just because unemployment is low, we’re not going to necessarily move monetary policy. Let’s look at the economy more broadly, but also more disaggregated so we really can understand whether we’re at that maximum employment goal that we have.”

As part of his administrative housekeeping, President Joe Biden last week withdrew Judy Shelton’s nomination to the Fed’s board of governors, definitively ending any hope of her joining. Former President Donald Trump had renominated her for the new Congress in January before he left office, along with some two dozen other last-minute appointments that Biden has withdrawn.

The new administration has given no indication of who it might choose to fill the vacant seat on the board.