In President Trump’s first week in office, he issued a blitz of executive orders, but perhaps his most ambitious statement to date is his claim yesterday that he would order the Federal Reserve to cut interest rates.

“I’ll demand that interest rates drop immediately,” he said at a virtual address to the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland. He paired his comment on rate cuts with a call for Saudi Arabia to reduce oil prices.

“I’m going to ask Saudi Arabia and OPEC to bring down the cost of oil,” Trump said, later adding: “With oil prices going down, I’ll demand that interest rates drop immediately.”

It’s an ambitious agenda, but the odds are low that Trump could, from the bully pulpit of the White House, issue orders that change interest rates and oil prices in a meaningful degree over time. Impossible? Maybe not. This, after all, is Trump and his political rise has come at the expense of numerous political norms that are now buried under the rubble of the collapsed old-world order that was Washington pre-2016.

But while Trump has a history of getting what he wants, and beating the odds along the way, he’s set a high bar with interest rates and oil prices that will likely be difficult, if not impossible, for the president to control. What’s different here is that rates and oil are set globally, driven by a mix of supply and demand data, economic indicators, investor sentiment, rank speculation, and many other factors. The idea that any one person – even the most powerful person on the planet – can dictate oil prices and interest rates is akin to assuming that you can easily grab a couple of eels out of a bucket of water.

Let’s start with interest rates. The Federal Reserve controls the short end of the yield curve and presumably, Trump’s plan would be to order the central bank to lower the target rate whenever he decides it’s time to ease monetary policy. In theory, that’s possible, but several things would need to happen first, perhaps starting with Trump firing Fed Chairman Jerome Powell, who would likely refuse to follow the president’s directive on rates.

Could the president fire the Fed head? “No,” Powell told reporters in November. “Not permitted under the law.”

Laws can be changed, of course, and Republicans control both houses of Congress. But we’re a long way from rewriting the rules for the Fed’s operations. Never say never, but I’ll go out on a limb here and predict such a huge change — and one that would likely upend markets — in the status quo for US central banking is unlikely.

But let’s indulge in a thought experiment and imagine Congress gives the president the power to set interest rates, which would make the Fed little more than the White House’s errand boy. Even in such an alternative universe, the president’s newly acquired monetary powers would only directly apply to the Fed funds target rate, which casts a long shadow over short-term yields. Further out on the maturity curve is a different story.

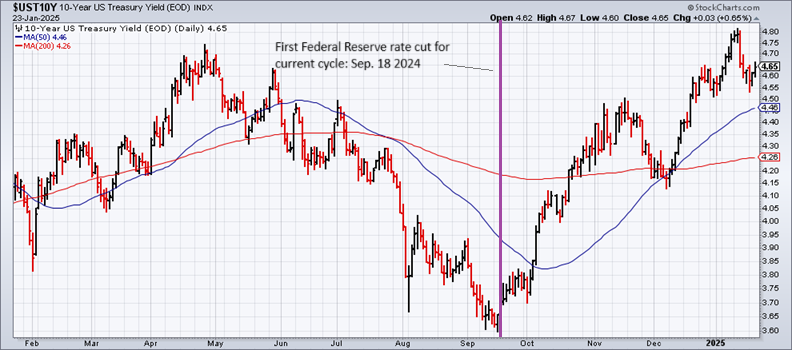

Case in point: the Fed announced its first rate cut for the current cycle on Sep. 18, 2024.

But expecting longer maturities to act in lockstep with Fed decisions is assuming too much. In the four months since the Fed first reduced its target rate (followed by two more cuts), the 10-year Treasury yield has increased by roughly 100 basis points. And since long rates determine the cost of borrowing, this is where most of the economic significance lies vis-a-vis changes in interest rates.

Perhaps the president would have more success lowering oil prices. Although Saudi Arabia is only one of several members of the OPEC cartel, the kingdom does have an outsized influence over crude prices, thanks to the country’s ample reserves – the world’s second-largest. No less important is the low cost per barrel to pump Saudi oil – the lowest among producers.

But while Saudi influence on global prices is significant, it’s not absolute. There’s also the question of whether the kingdom would play ball with Trump. Possibly, although under what conditions (and price tag) is open for debate.

Even if the House of Saudi is willing to do a deal with Trump, it’s not obvious that oil prices will quickly fall significantly for any length of time. The history of OPEC – a cartel that’s intent on manipulating oil prices to maximize profits for its members – has had mixed results over the decades since its founding in 1960.

To be fair, Trump is hardly the first president to cajole the Fed and oil producers. Nixon, for example, famously pressured Fed Chairman Arthur Burns to expand the money supply for political purposes in the run-up to the 1972 election. The results, however, weren’t encouraging.

Ultimately, global markets will determine medium- and long-term interest rates and oil prices. The caveat for Trump is that politicians who try to circumvent markets eventually lose. The price discovery mechanism, unlike politicians and bureaucrats, can’t be suppressed, bought off or rendered inert for long.