Time and technology can certainly change the dynamics of anything. In the past, only regulatory bodies and journalists would investigate high-profile politicians, businesspersons, athletes, movie stars and rock stars owning assets through an “offshore entity”, but now, even social media talks of offshore structures being exposed and scrutinising tax havens.

What are these “offshore structures” and why have they become the preferred choice of the ultra-rich?

According to law firm FDMA, in terms of corporate vehicles, “offshore financial centres” (OFCs) are locations that host financial activity separated from major regulating units by geography and/or legislation. Companies established in such locations are called offshore entities. Some well-known OFCs are Bermuda, the British Virgin Islands, the Cayman Islands, Panama and Switzerland. However, it is important to note that the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) does not define the term “offshore”.

|

Offshore Company Benefits |

|---|

|

Asset Protection |

|

Better Privacy |

|

Ease of Incorporation |

|

Tax Optimization |

Are offshore entities illegal? Surprisingly, the answer is “no”.

There are legitimate reasons for establishing an offshore entity, such as the following:

-

Financial privacy: protection from extortion (common in countries such as Mexico)

-

Legal framework: certain OFCs provide better legal and judicial facilities than an individual’s home country

-

Better banking infrastructure: in some jurisdictions such as Peru, it is a tedious process to get bank affiliation, hence they prefer setting up companies in OFCs

-

Lower tax rates: certain OFCs allow low or no capital gains tax through indirect asset transfers

However, certain loopholes in the law enable individuals to avoid paying taxes by moving their cash around, but this is considered unethical. Offshore entities are sometimes used for the following purposes:

-

Hiding money or not reporting earnings for purposes of tax evasion

-

Hiding ownership from law enforcement authorities, as the entity uses proceeds of crime or uses cash for financing terrorist activity, or the entity is used for laundering money

A number of investigations have been launched to assess whether such entities have been established to conduct legal business.

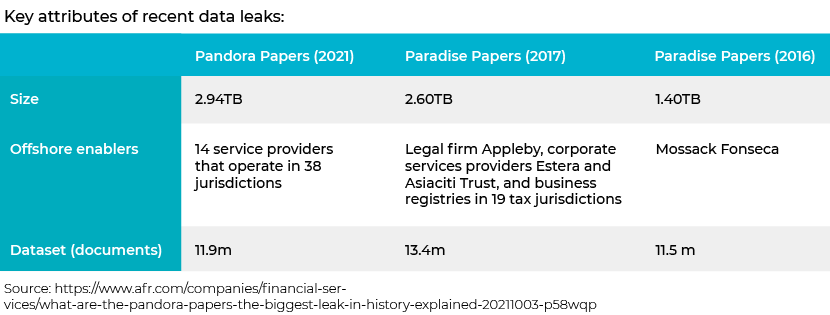

Investigations conducted by the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has led to publishing the Panama Papers (2016), the Paradise Papers (2017) and most recently the Pandora Papers (2021).

These leaks disclose confidential documents relating to offshore investments by wealthy individuals and public officials.

Highlights of the Pandora papers:

-

The following issues are discussed in the Pandora Papers: creation of shell companies, foundations and trusts, and the use of such entities to purchase yachts, jets, real estate and life insurance; make investments and move money between bank accounts; estate planning; avoid taxes through complex financial schemes; and engage in financial crime including money laundering

-

Some files date to the 1970s, but most of those reviewed were created from 1996 to 2020

|

Volume |

2.9TB |

|

Leaks from how many firms |

14 |

|

Global politicians named |

330 |

|

From how many countries |

90 |

|

Forbes billionaires named |

More than 130 |

|

Who are worth more than |

$US600bn |

|

Journalist involved |

More than 600 |

|

From how many countries |

117 |

It is estimated that USD32tn could be hidden in OFCs from being taxed (list); this is more than any country’s GDP (the US reported the highest GDP of USD22tn as of 2020)

Notable individuals named in the Pandora papers – from Forbes billionaires and celebrities to leaders of religious groups:

Following the leaks of the Panama and Paradise Papers, the governments of a number of countries started investigations, considered formulating legislation to regulate companies and even doubled their scrutiny of the trust sector. The following are some examples:

-

The European Union (EU) announced plans to tighten corporate oversight, forcing companies to publicly identify their real owners and give permanent status to temporary investigative committees

-

The Australian Taxation Office started investigating 800 Australians, stating that some of the cases may be referred to the country's Serious Financial Crime Task Force (source: link)

-

France restored Panama to its tax havens list, from which it had recently been removed (source: link)

-

Clients of Mossack Fonseca were fined USD440,000 by the regulators of the British Virgin Islands for breaching counter-terrorist financing (CTF) and anti-money laundering (AML) regulations. The fine was the highest ever levied by the regulator (source: link)

-

The National Directorate of Taxes and Customs of Colombia launched an investigation of all 850 clients of Mossack Fonseca Colombia, a subsidiary of Mossack Fonseca that was established in 2009. In 2014, Colombia had placed Panama on its blacklist of tax havens (source: link)

All these leaks have forced governments to adopt tax transparency measures but stop short of requiring full transparency. The following are some initiatives that could be taken to stop tax abuse and hold tax accountable:

-

Anti-money laundering obligations to be extended to private-sector intermediaries such as corporate services providers

-

Example: According to the EU’s Fifth Anti-Money Laundering Directive (the Directive), the scope of due diligence is to be extended to high-value dealers, digital-currency providers and auditors and tax advisors. The Directive also requires due diligence to be performed on all parties involved in transaction(s) crossing the EUR10,000 (USD11,000) threshold

-

-

Recovery of money –progress is slow, but

-

Twenty-three countries have recovered at least USD1.2bn in taxes

-

Heads of government implicated in corruption or tax avoidance have resigned or faced prosecution

-

There have been investigations in at least 82 countries

-

-

Supervisory and regulatory bodies to have the ability to penalise or suspend licences of businesses or professionals that do not meet AML and CTF standards

-

Global registry to identity of ultimate beneficial owners (UBOs) of companies

-

In addition to collaboration between global investigating agencies, a global centralised investigative agency could handle the problem more efficiently

In most countries, moving money through offshore accounts is not considered illegal, and many of the individuals named in the Pandora Papers are not accused of wrongdoing. However, according to the investigators, the focus is on the fact that the “offshore money machine operates in every corner of the planet, including the world’s largest democracies” and involves some of the world’s most well-known banks and legal firms. Hence, it is of utmost importance that OFCs not become a breeding ground for tax evaders and money launderers.

Which stock to consider in your next trade?

AI computing powers are changing the Canadian stock market. Investing.com’s ProPicks AI are winning stock portfolios chosen by our advanced AI for Canada, the US, and other exciting markets around the globe. Our top strategy, Tech Titans, nearly doubled the S&P 500 in 2024 - one of the most bullish years in history. And Beat the TSX, designed for broad market exposure, is showing +878% gains with 10 years’ back-tested performance. Which Canadian stock will be the next to soar?

Unlock ProPicks AI