“The stock market is not the economy.”

Such is the latest rationalization to support the “bull market” narrative. The question, however, is the validity of the statement. During the 2020 economic shutdown and surging market rebound, I stated:

“There is currently a ‘Great Divide’ happening between the near ‘depressionary’ economy versus a surging bull market in equities. Given the relationship between the two, they both can’t be right.”

Of course, as we now know, the market ran well ahead of economic growth, and in 2022, much of the market declined to realign with economic realities.

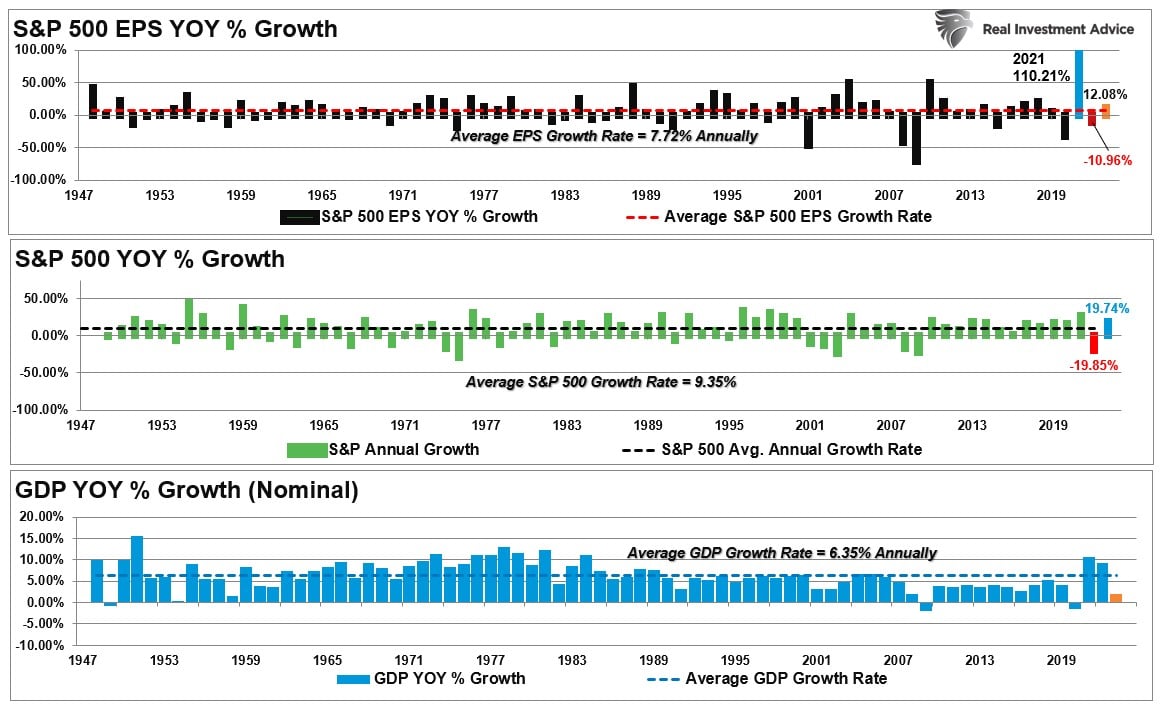

Such should be unsurprising given the close relationship between the economy, earnings, and asset prices over time. The chart below compares the three going back to 1947 with an estimate for 2023 using the latest data points.

Since 1947, earnings per share have grown at 7.72% annually, while the economy has expanded by 6.35% annually. That close relationship in growth rates should be logical, particularly given the significant role that consumer spending has in the GDP equation.

Important note: The massive expansion in earnings due to the stimulus-related surge boosted the EPS average higher by over a percentage point. A normal EPS expansion in 2020 would have maintained the average at 6.35%, equating to economic growth.

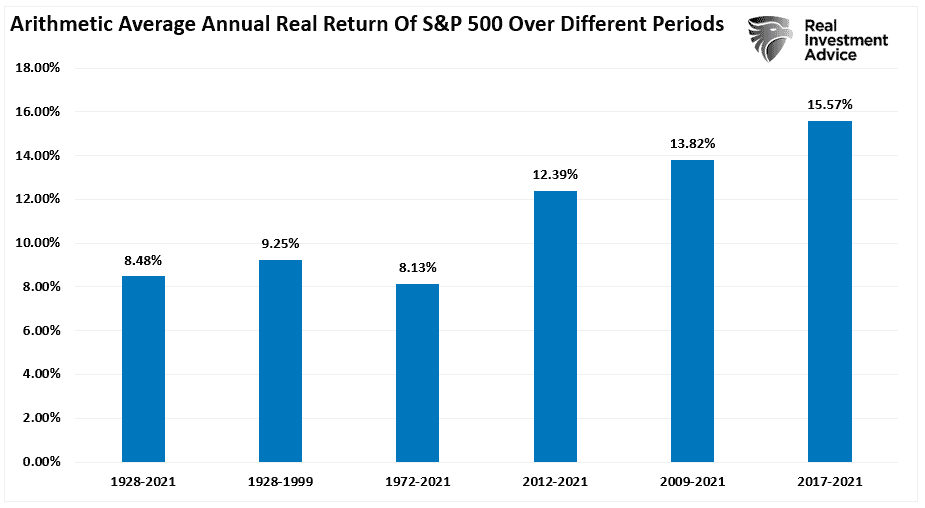

Furthermore, the annual average growth of the S&P 500 has been skewed significantly higher by the Fed’s monetary interventions. The long-term average growth Pre-Fed was 8% on average. Post-Fed interventions, that average has risen to over 9%. Such is shown more clearly in the following chart.

However, after a decade, many investors became complacent in expecting elevated rates of return from the financial markets. In other words, the abnormally high returns created by massive doses of liquidity became seemingly ordinary. As such, it is unsurprising that investors developed many rationalizations to justify overpaying for assets.

More Evidence of Market Excesses

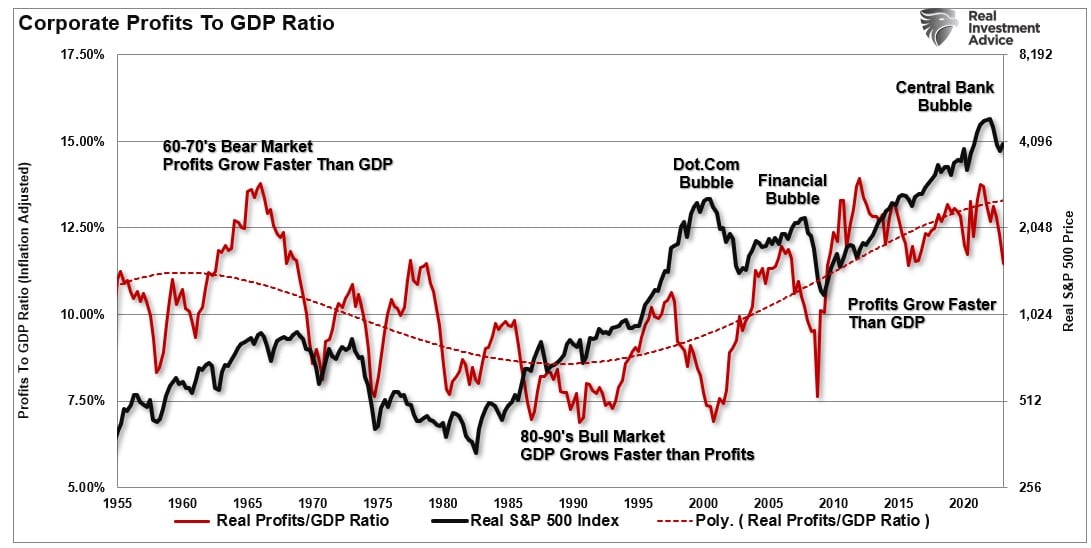

When it comes to the state of the market, corporate profits are the best indicator of economic strength.

Detaching the stock market from underlying profitability guarantees poor future outcomes for investors. But, as has always been the case, the markets can certainly seem to “remain irrational longer than logic would predict.”

However, such detachments never last indefinitely.

“Profit margins are probably the most mean-reverting series in finance, and if profit margins do not mean-revert, then something has gone badly wrong with capitalism. If high profits do not attract competition, there is something wrong with the system, and it is not functioning properly.” – Jeremy Grantham

As shown, when we look at inflation-adjusted profit margins as a percentage of inflation-adjusted GDP, we see a process of mean-reverting activity over time. Of course, those mean reverting events always coincide with recessions, crises, or bear markets.

Such should not be surprising as asset prices should eventually reflect the underlying reality of corporate profitability, which are a function of economic activity.

More importantly, corporate profit margins have physical constraints. Out of each dollar of revenue created, there are costs such as infrastructure, R&D, wages, etc. One of the biggest beneficiaries of expanding profit margins has been the suppression of employment, wage growth, and artificially low borrowing costs. The next recession will cause a rather marked collapse in corporate profitability as consumption declines.

Recessions Reverse Excesses

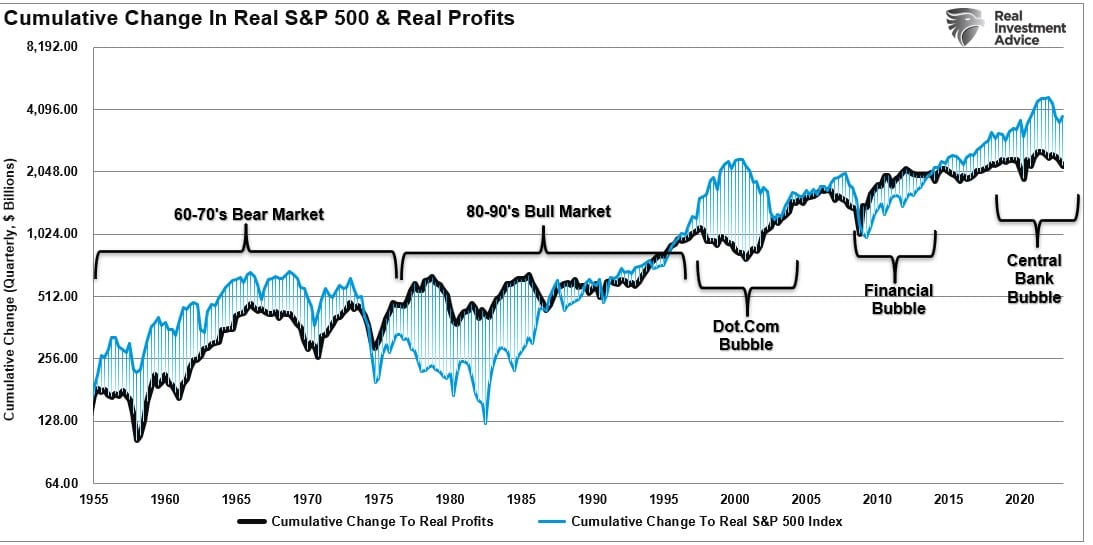

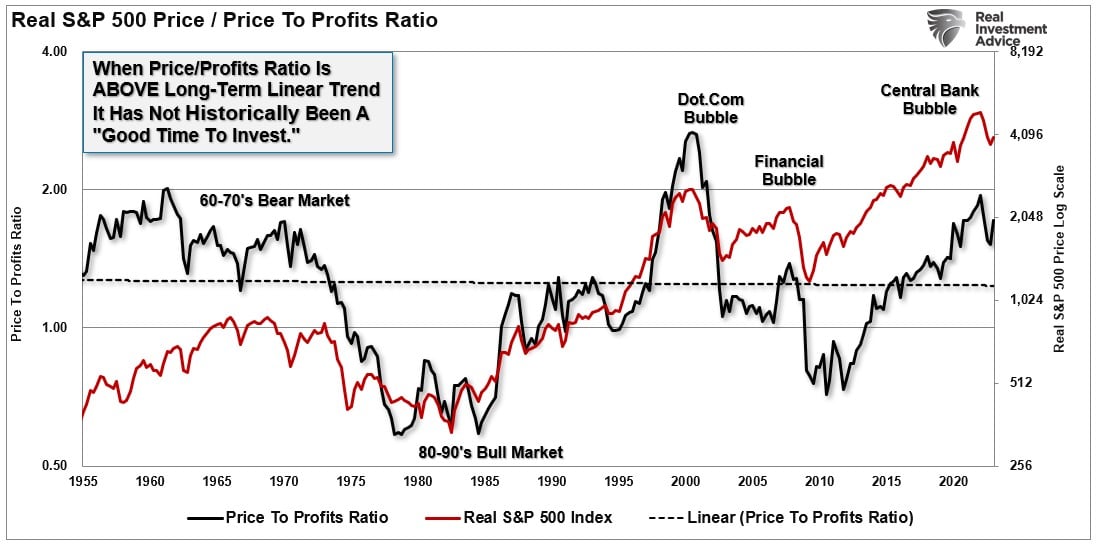

The chart below measures the cumulative change in the S&P 500 index compared to corporate profits. Again, we find that when investors pay more than $1 for $1 worth of profits, those excesses are reversed.

The correlation is more evident in the market versus the price-to-corporate profits ratio. Again, since corporate profits are ultimately a function of economic growth, the correlation is not unexpected. Hence, neither should the impending reversion in both series.

To this point, it has seemed to be a simple formula: as long as the Fed remains active in supporting asset prices, the deviation between fundamentals and fantasy doesn’t matter. It remains a hard point to argue.

However, what has yet to complete is the historical “mean reversion” process which has always followed bull markets. This should not surprise anyone, as asset prices eventually reflect the underlying reality of corporate profitability and economic growth.

The problem is that replicating post-Financial Crisis returns becomes highly improbable unless the Federal Reserve and Government commit to ongoing fiscal and monetary interventions. Without those fiscal and monetary supports, economic growth should return to previous growth trends of sub-2% due to increased debts and deficits.

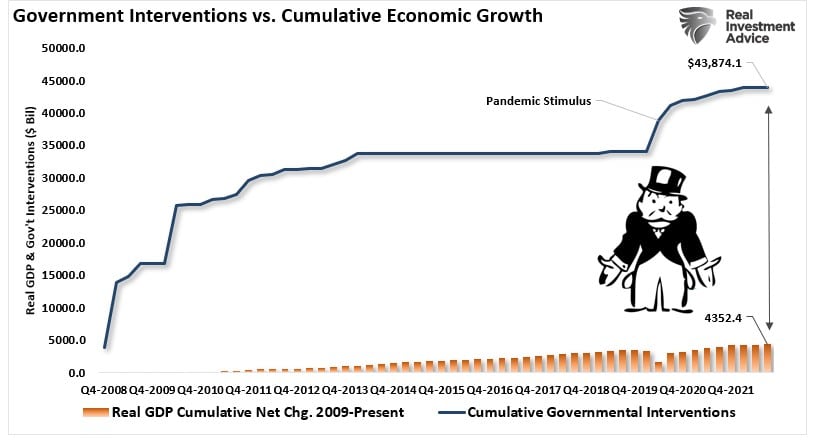

Look at the chart below, which compares the total monetary and fiscal interventions to economic growth. The market disconnect from underlying economic activity over the last decade was due almost solely to successive monetary interventions leading investors to believe “this time is different.” The chart below shows the cumulative total of those interventions that provided the illusion of organic economic growth.

Over the next decade, the ability to replicate $10 of interventions for each $1 of economic seems much less probable. Of course, one must also consider the drag on future returns from the excessive debt accumulated since the financial crisis. That debt’s sustainability depends on low interest rates, which can only exist in a low-growth, low-inflation environment. Low inflation and a slow-growth economy do not support excess return rates.

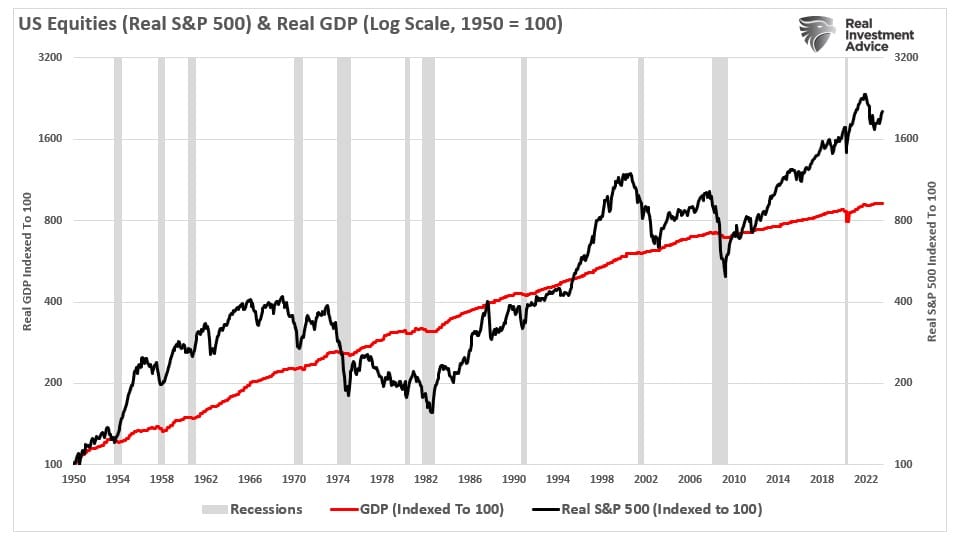

However, it is common for the market to become detached from the underlying economic activity for long periods as speculative excess detaches the market from underlying fundamental realities. Such is clearly shown in the chart below, which compares the stock market to GDP on an inflation-adjusted basis. In all cases, market excesses eventually “mean revert.” The only issue is the catalyst that causes it.

It is hard to fathom how forward return rates will not be disappointing compared to the last decade. However, we must remember those excess returns resulted from a monetary illusion. The consequence of dispelling that illusion will be challenging for investors.

Will this mean investors make NO money over the decade? No. It means that returns will likely be substantially lower than investors have witnessed over the last decade.

But then again, getting average returns may be “feel” very disappointing to many.