US economic activity looks strong or weak, depending on the data sets you choose to craft a narrative. That’s always true in some sense for the simple reason: there’s always some slice of the economy bucking the broader trend. But this time is different because the degree of the conflicting signals is so stark.

The poster boy for growth and thinking positively is the labor market, which continues to post strong gains – far stronger than other indicators suggested in previous decades that offered relatively reliable business-cycle signals.

The debate is whether the surprisingly robust gains in payrolls of late are due to extraordinary one-time factors linked to the ongoing effects of the pandemic. So-called labor-hoarding is one theory. If there’s something different this time, can it reverse suddenly? Or is it persistent?

Regardless of the explanation (and the staying power, or lack thereof), there’s no denying the numbers. US unemployment remains low, and payrolls are rising steadily: payrolls rose 517,000 in January, the highest monthly gain since July. Meanwhile, the jobless rate ticked down to 3.4%, the lowest since the 1950s.

Other key areas of the economy are strong as well. Notably, although wobbly in recent months, consumer spending shows a strong ability to bounce back. Personal consumption expenditures surged 1.8% in January, the most in nearly two years.

Definitions of a recession vary, but it’s a safe assumption that the economy will almost certainly avoid contraction if payrolls and consumer spending are robust. That doesn’t change the fact that key indicators otherwise continue to flash warnings. For example, the inverted Treasury yield curve. Rising interest rates and unusually steep declines in money supply are other portents.

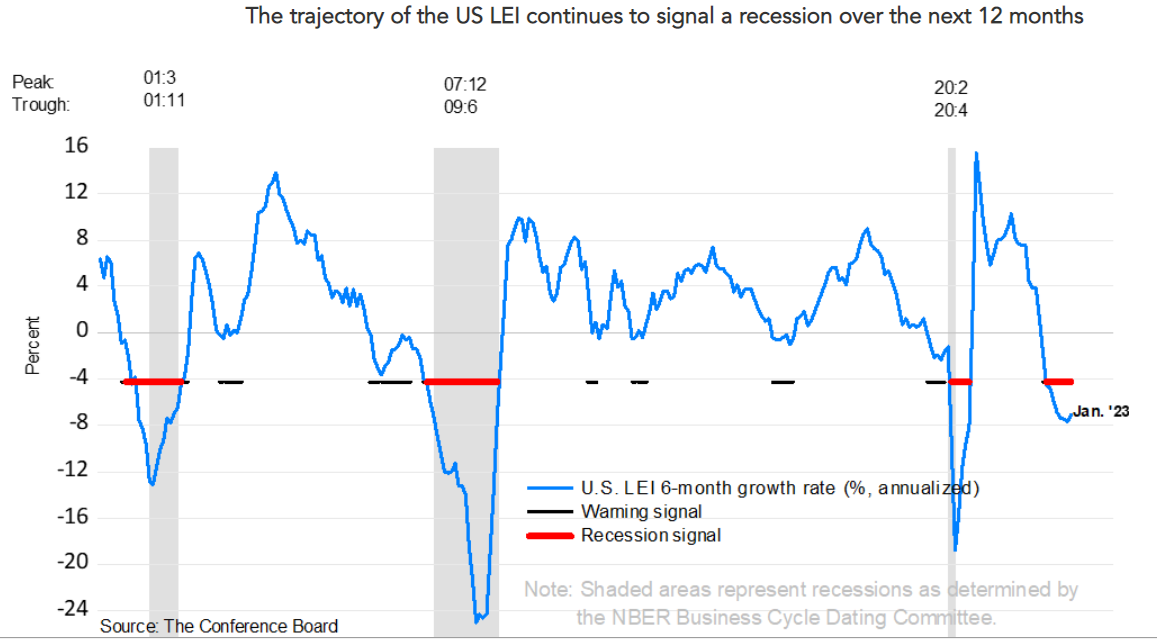

Several broad-minded measures of the business cycle look downright ominous. For instance, the Conference Board’s Leading Economic Index in January paints a dark profile.

But the labor market suggests otherwise. The crucial question: Which side will blink first? In search of an answer, watching payrolls and related numbers will offer early clues on how this mystery resolves. On that front, keep an eye on what could be hints of weaker data for payrolls in the next round of updates.

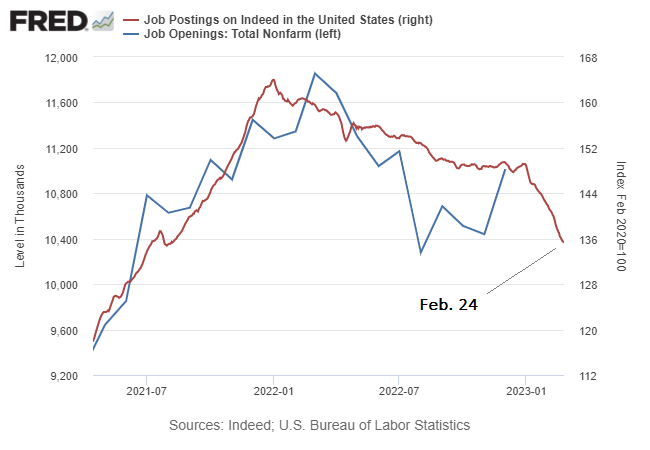

Job postings on Indeed.com, a jobs platform, suggest that the recent strength in the labor market is reversing and that rise in job openings will continue to reverse.

Analysts at other platforms report similar results. Julia Pollak, the chief economist at ZipRecruiter, said,

“We haven’t seen [the slowdown] in the employment data yet, but we will see it soon. We also speak to customers all of the time. We discuss with them their plans for future hiring. They are telling us they are worried about the risk of overhiring.”

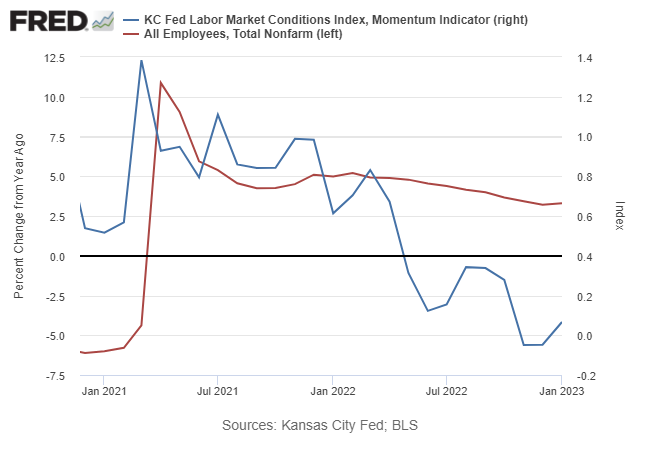

The Kansas City Labor Market Conditions Index is trending lower, which implies that the strength in year-over-year payrolls will soon weaken.

The question is whether the warning signs will continue to be one more case of premature and possibly misleading indicators. This much is clear: the usual conditions for evaluating the business cycle are issuing conflicting signals. We may be in the middle of a learning experience that rewrites how analysts evaluate business-cycle risk.

Meanwhile, it’s hard to argue that a recession is near as long as the labor market remains tight and hiring is robust. Until the hard data on this front tells us otherwise, payrolls appear to be the only game in town to decide if the business-cycle risk is high or low.