By Miguel Gutierrez and Juan Dominguez

MADRID (Reuters) - Spain became the first Western European country to exceed 1 million COVID-19 infections on Wednesday, doubling its tally in just six weeks despite a series of increasingly stringent measures to control the second wave of the virus.

Health ministry data showed total cases had reached 1,005,295, rising by 16,973 from the previous day. The death toll increased by 156 to 34,366.

After slowing to a trickle in the wake of Spain's strict March-to-June lockdown, the infection rate accelerated to frequently exceed 10,000 cases a day from late August, hitting a new peak of more than 16,000 last week.

Many blame impatience to be rid of state-imposed restrictions meant to contain coronavirus contagion, or weariness with social distancing guidelines.

"We are less responsible, we like partying, meeting with family," said banker Carolina Delgado. "We haven't realised the only way... is social distancing, simple things like not gathering with many people, wearing masks even if you meet friends."

A hurried exit from confinement before tracing systems were in place let transmission get out of hand faster than in other countries, said Dr. Rafael Bengoa, co-founder of Bilbao's Institute for Health and Strategy.

He also blamed Spain's deeply entrenched political polarisation for the rise. "There's a lot of political noise but a shocking leadership vacuum," he said.

As the health ministry released the latest figures, most of its lawmakers were bitterly debating a motion of no confidence in Socialist Prime Minister Pedro Sanchez launched by the far-right Vox party.

"These politicians are only comfortable with the simplicity of short-term..., ideologically motivated debates, but the virus doesn't care about ideology," Bengoa said.

While daily deaths have been hovering around 100 - a far cry from the peak of nearly 900 registered in late March - hospital admissions have jumped 20% nationwide in two weeks and 70% in the affluent northeastern region of Catalonia alone.

That may potentially force some Barcelona hospitals to suspend non-urgent procedures.

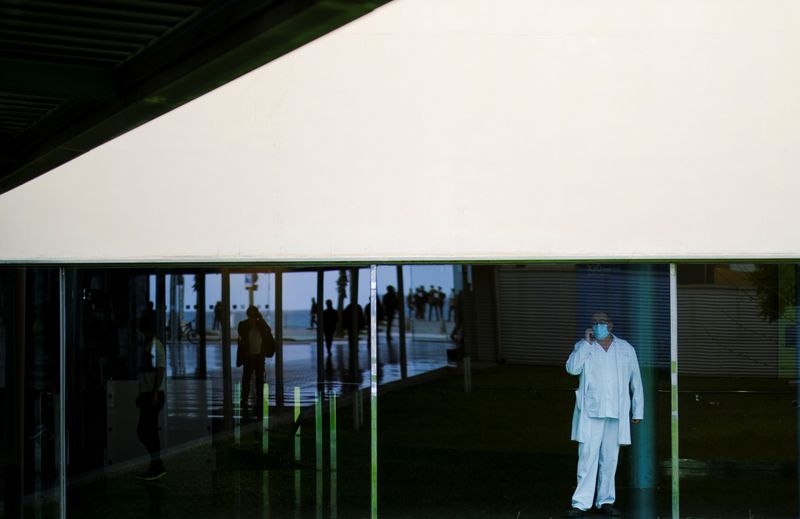

Sergio Hernandez, a nurse in Madrid, suggested higher fines and more exhaustive controls of positive cases, adding that current follow-up protocols were not very good and probably amplifying the rate of infections.

Desperate to avoid a repeat of the first wave, when the virus ravaged Spain's elderly population and brought the health service to its knees, several regions have indeed returned to tougher restrictions in the past weeks.

The government is also contemplating curfews for the worst-hit areas, including the capital Madrid, where a two-week state of emergency is due to expire on Saturday.

Conservative regional leader Isabel Diaz Ayuso, who has regularly locked horns with the left-wing national government, said she would prefer more "surgical measures" that do not penalise businesses.

"What's most important is that the economy doesn't suffer any more," she told a news conference on Wednesday.

That view was shared by some Madrilans like civil servant Luis Calvino, who believes policy on health and the economy should be coordinated. "If we want to have enough medical capacity, it all costs money, which comes from taxes."