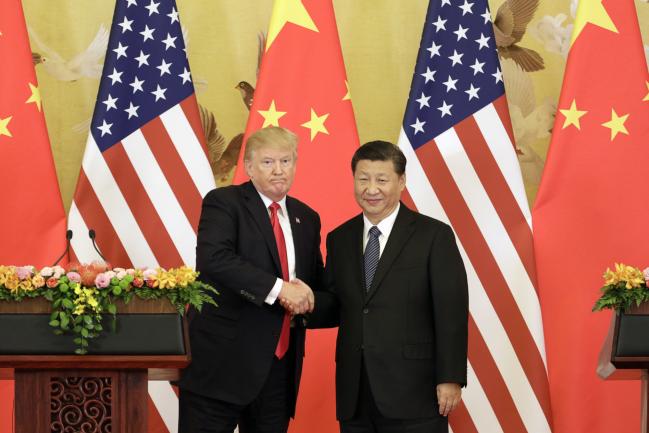

(Bloomberg View) -- Trade war! Those dread words are on everyone’s lips (and electronic equivalents) as President Donald Trump and China’s President Xi Jinping throw out a series of rapidly escalating tariff threats:

President Donald Trump fired a shot at China’s plans to dominate strategic technologies, proposing tariffs on 1,300 goods from semiconductors to flamethrowers. China hit back hard today, targeting politically sensitive goods like soybeans, automobiles and aircraft with retaliatory duties.

Trump economic adviser Larry Kudlow, a free-trade advocate, tried to walk back the threats, but this president isn't necessarily guided by the opinions of even his closest advisers.

QuickTake Free Trade and Its Foes

The specter of a large-scale trade war between the world’s two biggest economies -- an event unprecedented in modern times -- has people scrambling to anticipate the effects. Most analyses are focusing on regions and industries that will be directly hurt or helped by the tariffs. The Brookings Institution has a great map showing how dependent various regions’ economies are on exports. A lot of the most vulnerable places are in Trump country, including Michigan, Indiana, North Carolina, Louisiana and Texas.

Looking at specific industries, China’s tariffs on agricultural products can be expected to hurt farming states, many of which voted for Trump in 2016:

U.S. manufacturing giants that sell products in China, such as Apple (NASDAQ:AAPL), Boeing (NYSE:BA), Caterpillar (NYSE:CAT), General Motors (NYSE:GM) and Intel (NASDAQ:INTC), are also expected to take a hit if China follows through on its threats.

But Chinese tariffs aren’t the only ones that will hurt U.S. companies -- Trump’s own import taxes could be a self-inflicted wound as well. His tariffs on steel and aluminum have already increased prices for U.S. manufacturers that use these metals as inputs:

Trump’s new round of tariffs would have similarly negative consequences for the U.S. pharmaceutical industry, which makes heavy use of ingredients produced abroad. And Trump’s taxes on power-generating equipment will hurt companies that build and operate power plants, while raising prices for electricity consumers.

This illustrates a fundamental principle of trade wars -- there’s only one group of beneficiaries, but two groups of victims. Companies directly protected by new tariffs win, but companies that use foreign-made inputs and companies that sell into foreign markets both lose.

That’s why the most basic economic theories predict overall losses from trade wars. The Trump-Xi Trade War of 2018, if it materializes, will be something of a test for those theories. If large economic losses result, it will serve as vindication for the many economists, think-tank researchers and pundits who believe trade war is a net loser.

On the other hand, it’s possible the harm will be limited. U.S. companies and consumers might be able to easily shift from Chinese suppliers to ones in Canada, Mexico, Southeast Asia or even the U.S. Chinese consumers might not be very sensitive to the price of U.S.-made goods, and U.S. producers might be able to easily switch to other markets in places like India, or Latin America. If that happens, economists will have to rethink their use of two-country models to describe the global trade system.

Is it possible that the U.S. could actually benefit from a tariff war? It could, but only if the war is over swiftly, and results in Chinese policy concessions that durably reduce trade distortions.

Economists have long known that trade barriers could be used as a strategic bargaining chip. If Trump uses his tariffs to force Chinese policy concessions rather than simply to posture, he could conceivably force China to reduce its systematic theft of U.S. intellectual property, to create a fairer, more level playing field for foreign companies, to reduce subsidies for its manufacturers, or to promise not to engage in currency manipulation. Any and all of these changes would end up making global trade freer in the long term.

So could the U.S. conceivably force China to make any of these concessions? Some argue that the U.S. has more leverage in a trade war, since it runs a trade deficit with China. When trade between the two countries falls, Chinese producers would almost certainly suffer more than American ones. Chinese investment in U.S. bonds would correspondingly fall, but that may not be a big danger -- U.S. investors would probably pick up the slack. In 2010, writing in support of using tariffs as a strategic tool to force China to appreciate its currency during the Great Recession, Paul Krugman explained:

What would happen if China tried to sell a large share of its U.S. assets? ... Long-term rates might rise slightly … [T]he Fed could offset any interest-rate impact of a Chinese pullback by expanding its own purchases of long-term bonds. … Right now America has China over a barrel, not the other way around.

Krugman was worried about Chinese imports reducing aggregate demand -- now that the recession is over, he no longer supports a trade war. But the fact that China probably has more to lose than the U.S. remains the same.

So maybe Trump is right, and that a trade war with China will be “easy to win.” But I wouldn’t bet on it. Every day that tariffs, or the threat of tariffs, stay in place in either country is a day that U.S. industry bleeds. As for the possibility of China’s government blinking first, the autocratic Xi is probably able to endure economic pain much longer than the democratically elected leaders of the U.S.

In other words, the safe bet is that this trade war will not end well for Trump, or for the U.S.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Noah Smith is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was an assistant professor of finance at Stony Brook University, and he blogs at Noahpinion.