By Allison Martell

TORONTO (Reuters) - The Canadian province of Ontario will push for the federal government to tackle the high cost of treatments for rare diseases as negotiations over a new national prescription drug program are set to kick off, the province's health minister told Reuters on Monday.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau's Liberal Party, which was reduced to a minority government following the October election, made a universal pharmacare program a key campaign promise of their re-election bid, without offering much detail on how it might work. The details will need to be negotiated with provincial and territorial governments, responsible for delivering most healthcare.

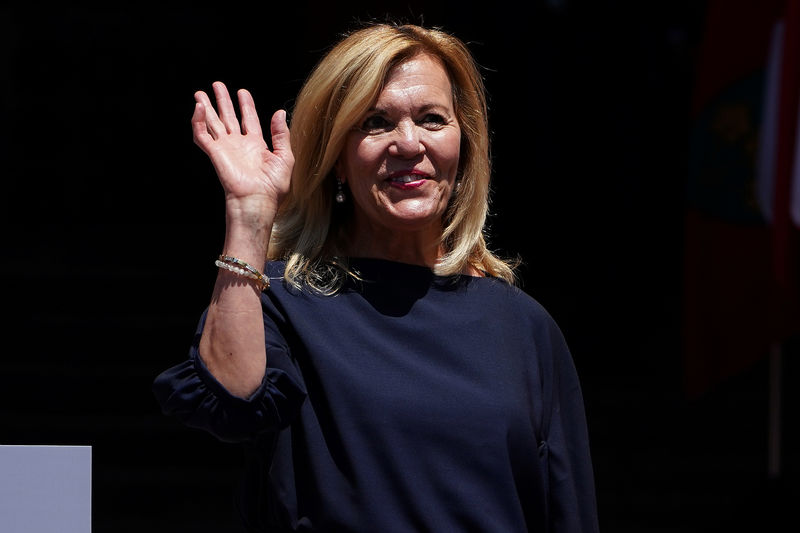

"I think that we should start with where we see a real problem, and Ontario sees a real problem with the rare and orphan disease drugs," Christine Elliott, the provincial health minister, said in an interview.

"On the other issues, we don't see that there's a problem, with respect to Ontario."

There is likely room for consensus on rare diseases, as the federal government promised a new national strategy to improve access to the drugs in the last budget. But since by definition few patients have rare diseases, a program focused there would not get Canada much closer to the universal coverage Trudeau promised.

While rare disease treatments face small markets, the extremely high prices they command and policies that speed their approval have made them a hot and profitable niche for drugmakers.

Elliott said she told new federal Minister of Health Patty Hajdu during a call on Friday that provincial and territorial ministers would like to teleconference early in the new year and meet in the spring on a number of issues, including drug costs.

Canada is the only developed country with a universal healthcare system that does not cover prescription drugs for all, although a patchwork of programs support older Canadians and people with low income or very high costs. Most rely on employer-funded plans to pay for medicines.

Trudeau's Liberals will need the support of rivals like the left-leaning New Democratic Party (NDP) to govern. The NDP has pushed for a comprehensive, single-payer drug program.

Ontario, with a right-wing populist premier, Doug Ford, is one of several provinces led by rival parties.

If too many provinces opt out of pharmacare, that would weaken the program as lower participation means less bargaining power in buying drugs. As Canada's most populous province, Ontario is particularly important, but the promise of billions in new federal funding could make a deal possible.

Elliott also said the province needs to make a decision on whether to switch patients to biosimilars, cheaper near copies of expensive biotech drugs for which exact generic copies are not possible.

The decision by the province of British Columbia in May to switch thousands of patients on its public drug plan to biosimilars kicked off a backlash among some drugmakers and patient groups, who argue that switching therapies might hurt some patients doing well on the older, more expensive drugs.

Health Canada disagrees. The agency has said patients should not expect any change in the efficacy or safety when they switch to a biosimilar.

"Any decision that we make in health is going to be based on evidence," Elliott said.