By David Ljunggren

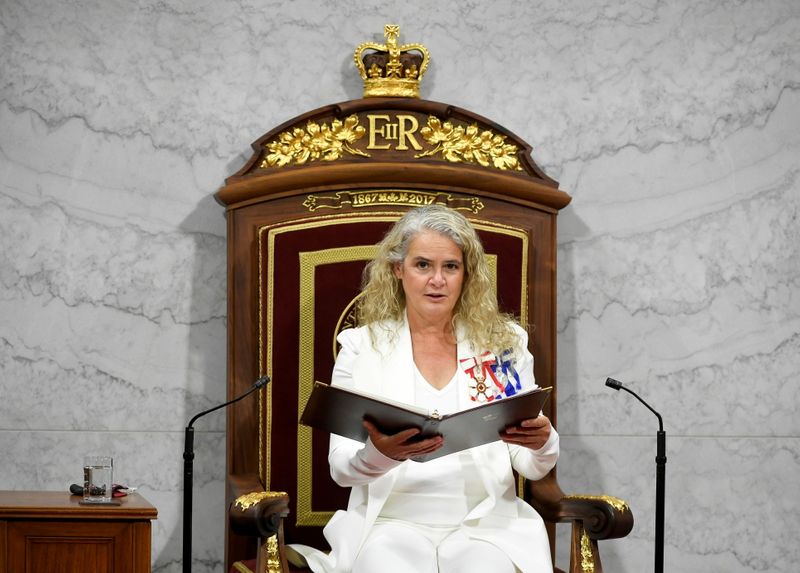

OTTAWA (Reuters) - Canadian Governor General Julie Payette, the representative of the country's head of state, Queen Elizabeth, quit on Thursday amid allegations of workplace harassment in an embarrassment for Prime Minister Justin Trudeau.

The resignation has no immediate implications for the Liberal government. The governor general has a largely ceremonial job such as swearing in governments and formally signing legislation, but can on rare occasions be asked to settle constitutional questions.

She resigned just hours after senior officials received the results of an independent probe into reports of verbal abuse and bullying by Payette.

"I have come to the conclusion that a new Governor General should be appointed. Canadians deserve stability in these uncertain times," Payette said in a statement, adding she was sorry for tensions that had arisen with staff.

She was the first governor general to quit under a cloud. Richard Wagner, chief justice of the Supreme Court, will temporarily take over her duties until she is replaced.

Payette, 57, took office in October 2017 for a five-year term on Trudeau's recommendation. Even after the probe was launched last July, Trudeau defended Payette, saying in September that she was "an excellent governor general."

She was formerly the country's chief astronaut and the first Canadian to serve on the International Space Station.

In a brief statement, Trudeau said the resignation meant workplace concerns in the governor general's office could be addressed. He notably did not thank Payette.

Trudeau is an avowed feminist, and Liberal officials said at the time that the appointment would advance the cause of women. Potential candidates for the job are supposed to be vetted by a special committee, a step Trudeau chose to ignore.

"The colossal failure of Ms. Payette's term falls squarely on his shoulders," said Don Davies, a legislator for the opposition New Democrats.

"It's not a constitutional crisis. ... There is a system in place to allow for continuity of the role," Barbara Messamore, a history professor and constitutional expert at the University of the Fraser Valley, told the CBC.