Street Calls of the Week

Background

Free-float shares refer to shares of a corporation in the hands of public investors and available for trade. Free float is an important metric that influences the price of a security. It is an indicator of liquidity. All the major indices were initially based on the full market capitalisation method, but free-float methodology was later considered by major index providers such as S&P, MSCI and FTSE Russell as an ideal methodology for calculating equity indices. This is because this methodology more accurately reflects market trends and market volatility.

Financial professionals and investors, including institutional investors, require index providers to create and provide viable indices with a sound and a clear purpose, although this purpose may vary from index to index. Such investors are dependent on such indices, as they provide real-time information on market performance. These datasets are used as inputs to make investment and economic decisions. These products (indices) are estimated to be benchmarked and linked to assets totalling over USD6tn. Investment professionals who manage these assets rely on specialised index providers for sound index construction, rigorous index maintenance and uninterrupted data distribution.

A brief look at free-float methodology

The main purpose of adopting free-float methodology is to adjust a company’s total shares outstanding for strategic shareholders whose holdings are not tradable in the market and obtain a clear picture of the company’s ownership structure. The free-float factor or investable weight factor (IWF) is the multiple with which we adjust total market capitalisation to arrive at free-float market capitalisation. It is determined based on the public shareholding of a company. Major index providers consider certain shareholders as non-free-float, and they are omitted regardless of whether they intend to exercise any form of control; they include the following:

-

Strategic shareholders

-

Shares held in lock-up (referring to IPO lock-up shares)

-

Institutional investors

-

Shares held by governments (directly/indirectly)

-

Shares held by sovereign wealth funds, etc.

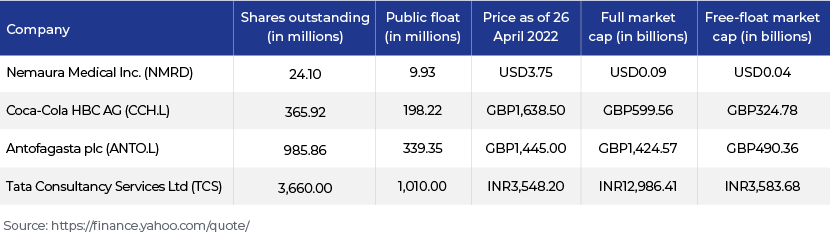

To understand this in detail, we look at a few companies to showcase how market capitalisation will differ if free-float shares are taken into consideration.

The table above separates the number of total shares from the number of free-float shares. The larger the percentage of free-float shares, the greater will be the liquidity of that stock. For example, there are 1,010m TCS shares available to be traded by financial professionals and investors.

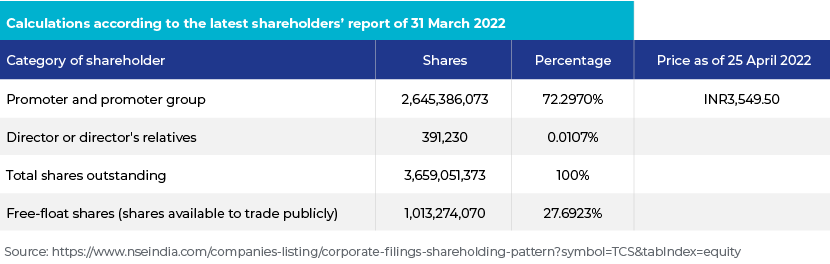

We consider TCS to demonstrate a sample calculation of free float based on the general understanding.

Financial professionals would use the details in the table above to understand who the major shareholders of TCS are, whether they could hold a majority stake for a future buyout of the company and whether they would be able to influence or modify the policies or decision making of the company through AGMs or other events. The table also shows whether a shareholder could have large voting powers based on the voting rights for this class of shares used for the purpose of calculating the float.

Implications of using wrong free-float values

If the float of an existing index member is wrongly calculated and published by the vendor, it could have an adverse effect on multiple levels such as the following:

-

The index is severely impacted, with the weights of the index member in question changed. This may lead to index exclusion for the company as well, triggering a selloff from multiple investor portfolios.

-

The investors, especially institutional investors, suffer large losses, as their portfolios are benchmarked to that index. Their positions are being squared off based on such announcements.

-

Overall, it impacts the business of the index provider, as the accuracy of its index and research is questioned by the investors.

Importance of free-float shares to market participants

For investors

Using free-float methodology in index calculation benefits active managers in their investment strategies by comparing their portfolio returns with the investable index. For passive investors, through their exchange-traded funds (ETFs), indexation firms enable passive investing for all investors by buying and selling stock in direct proportion to the content of the index they track. Furthermore, the percentage is regularly traded, boosting the number of shares and providing a quick exit for investors in the event of a loss.

For markets

Free-float shares affect a company’s share price on a daily basis. It depicts the number of marketable shares. If the free float of a company is low, it would mean there is a smaller number of tradable shares available for the public and vice versa. Additionally, companies with a lower free float are likely to experience higher price volatility because it takes fewer trades to manipulate the share price, and these companies often become the subject of speculating by day traders.

For the index

Under free float, an index's scope expands significantly, since companies with large market capitalisations or fewer free-floating shares can now be included in the index. Because only the company's free-floating capital is counted in the free-float market capitalisation, it is desirable to incorporate these types of enterprises in the index to improve the market.

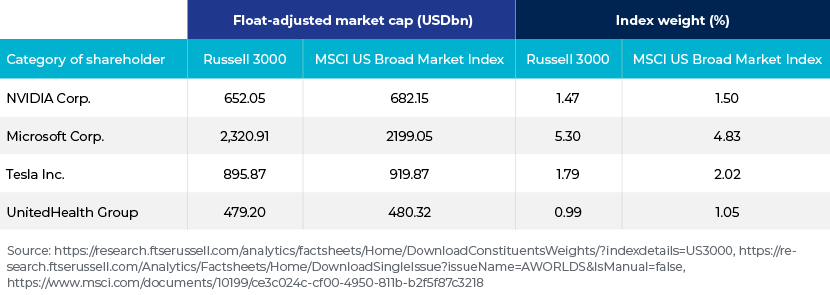

Multiple participants and their different approaches

While computing free-float weights for companies with complex ownership structures, index providers frequently use discretion in determining the float. In such instances, a thorough examination of the company's shareholder agreements is required. South Korea and Japan have horizontal cross-ownership shareholdings that make it difficult to determine free-float weights. Because index providers do not share detailed explanations of their process of determining free float-adjusted market capitalisation for individual companies, it is very hard for investors to simulate the free float in many scenarios. For a sample comparison of index weights of similar companies, the Russell 3000 (with 3,000 constituents) and the MSCI US Broad Market (with 3,133 constituents) indices have been considered.

From the table above, we understand that the two major index providers covering the same country with almost the same number of members in their indices can have different weights for the same company, as their methodology for calculating free float determines the company’s market cap, affecting the index weights as well.

Understanding the free-float calculation is a crucial part of building and maintaining an index. Index providers are very discreet and not all details of the methodology used are presented on their websites for the use of financial professionals. Such discretion gives index providers an edge over their datasets, but the difference in free-float values is a challenge for investors. Another shortcoming of free float is that company filings and information in the public domain are not available in a timely manner across the world; such filings in emerging or frontier markets lag those in developed markets.

Which stock should you buy in your very next trade?

With valuations skyrocketing in 2024, many investors are uneasy putting more money into stocks. Unsure where to invest next? Get access to our proven portfolios and discover high-potential opportunities.

In 2024 alone, ProPicks AI identified 2 stocks that surged over 150%, 4 additional stocks that leaped over 30%, and 3 more that climbed over 25%. That's an impressive track record.

With portfolios tailored for Dow stocks, S&P stocks, Tech stocks, and Mid Cap stocks, you can explore various wealth-building strategies.