The Fed’s meeting lived up to expectations: boring. Boring is fine. They kept the federal funds rate unchanged at a range of 4.25% to 4.50%. The only market reaction resulted from some heavy-handed editing of the FOMC statement that Fed Chair Powell had to explain away as “a little bit of language cleanup.” Today’s post reflects on three comments from Powell at the press conference that relate to the Fed’s current approach to policy, Fed independence, and economic uncertainty.

1. “We Don’t Need to Be in a Hurry.”

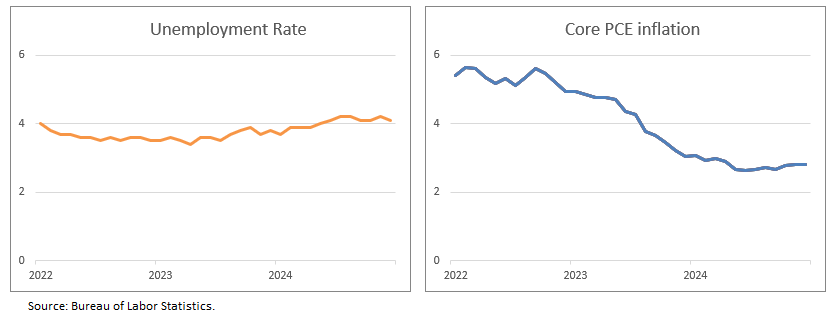

Powell repeatedly said the Fed is “not in a hurry” to adjust rates. There is logic in the Fed’s stance. The unemployment rate was 4.1% in December, and it changed little in the second half of the year. In addition, growth has been solid; on a four-quarter basis, real GDP rose 2.5% in 2024, well above the Fed’s 1.8% estimate of long-run growth.

What’s left is the “somewhat elevated” inflation. Core PCE inflation was estimated to be 2.8% in December. That’s considerable progress from the 5.6% peak in 2022, but it’s still some distance from the 2% target. The Fed views the level of the funds rate as restrictive; if so, it’s only a matter of time before it shows through to lower inflation.

Unless something changes with unemployment, we should expect the Fed’s pause to last several months—even if the inflation data are good. They want to “be confident” that inflation is going to 2%, and it will take several months of data to build confidence. Given the bumpiness of data, June or July is most likely.

We may get some ‘quick wins’ on inflation soon. Core PCE inflation was red hot in January 2024 at 0.5%, and dropping that out of the 12-month average could have a noticeable effect, assuming that the residual seasonality and start-of-year pricing effects are more muted this year. However, quick wins like that won’t shift the “not in a hurry” Fed. It will take time to build the case to cut again.

A slow-motion approach carries risks for monetary policy since its interest rate tools affect the economy with a lag. Being intentionally slow in cutting rates and requiring data in hand first risks more restrictions on the economy (such as less growth or less employment) than necessary to achieve 2% inflation. Uncertainty around the inflation outlook is so large—true before the threat of tariffs—that it’s hamstrung forward-looking monetary policy. Instead of a framework review, the Fed should have an inflation review.

2. “Policies Not For Us to Praise or Criticize.”

It was abundantly clear yesterday that Powell did not want to discuss President Trump or his policies. In its efforts to protect the independence of monetary policy, the Fed avoids (with very few exceptions) commenting on the actions of other economic policymakers.

The cost of silence is probably worth paying, but it can be tortured. Tariffs are one of the big wild cards for the economy right now. There is a live threat of 25% tariffs on Mexico and Canada for Saturday. However, Powell's discussion in the last two press conferences largely referred to staff Tealbooks in 2018 and 2019. Why not share the latest thinking from the most recent, e.g., January 2025, Tealbook? Because they don’t want to be publicly evaluating the Administration’s policy thinking. A soundbite of the Fed Chair explaining how tariffs really work and how damaging they would likely be to the economy is not worth it to the Fed.

Some form of new tariffs is likely. Once policies are enacted and their effects are in the data, the Fed will need to say more, especially if the economic effects inform their policy decisions. But they are truly in no hurry with that conversation.

3. “The Kind of Uncertainty We Have Is Just a Usual Level.”

Powell did his best to reduce the volume surrounding President Trump’s economic policy agenda, arguing that the uncertainty now is unremarkable. He pointed to times like the early months of the pandemic or the height of the Global Financial Crisis in 2008 as uncertainty.

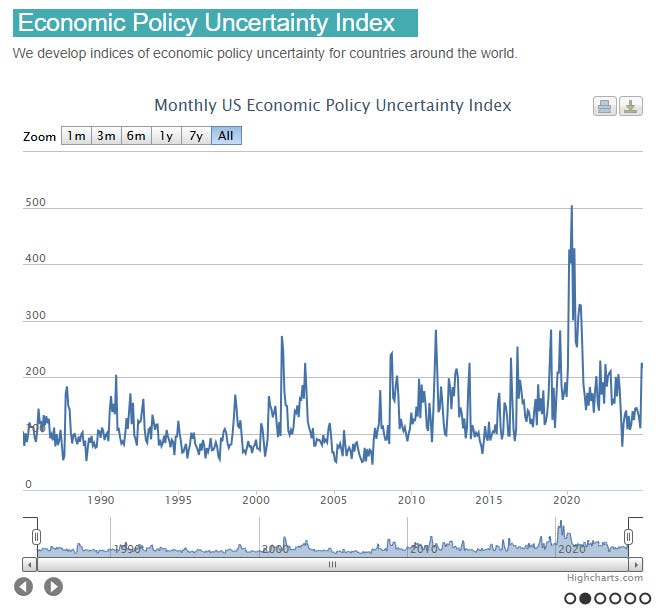

At least one measure of economic policy uncertainty (through December)—based on news reports—backs Powell up.

Policy uncertainty jumped after the election but stayed within the usual range of variation. Even if the index goes higher in January, it would likely still be dwarfed by the pandemic.

Not having pandemic-level uncertainty is a fairly low bar for comfort. The Fed wants to squeeze 0.8 percentage points of inflation out of the economy. If the policies being discussed now even add a half percentage point of inflation, it could be the difference between rate cuts this year and not. Powell is correct in setting our current challenges in the context of a very good economy, but they are still challenges.

In Closing

The Fed managed to be boring on Wednesday. Their wait-and-see approach is appropriate for the current moment, but it is unclear how long that will last.