This article was written exclusively for Investing.com

Thursday's Existing Home Sales report threw into stark relief, with a pertinent example, exactly what I have been talking about recently. Growth doesn’t cause inflation, and recessions don’t cause disinflation; so, while I am negative on the outlook for growth, I don’t expect that will be any help in cooling the fires of inflation.

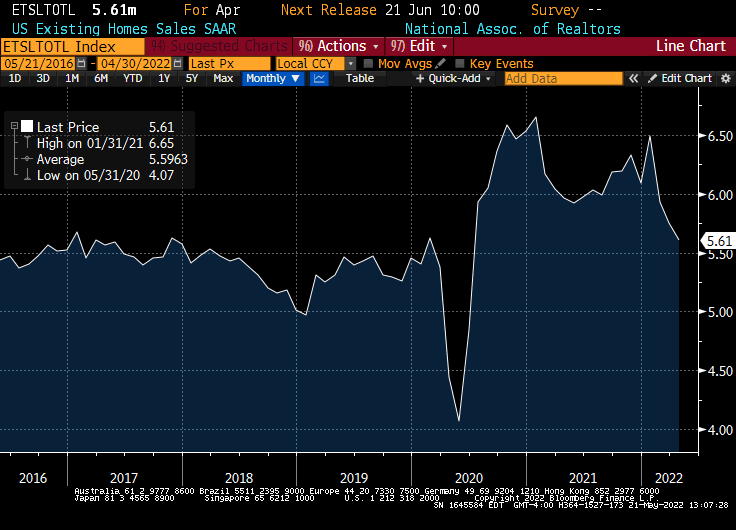

The Existing Home Sales report last week was disappointing, confirming the justified fears of homebuilders and realtors that higher mortgage rates and a slowing economy would deter traffic and turnover. By now, you know that home sales rose at a 5.61mm seasonally adjusted annual rate, which was lower than expectations and the lowest since the months of the pandemic shutdown. While that would still be a relatively healthy rate compared with the pre-COVID era, there is no question that the increase in interest rates is slowing turnover.

This effect is one of the more obvious ways that higher interest rates cause a slowdown in economic activity and is clearly an outcome that is intended by the Federal Reserve. Slow down the red-hot housing market and cool the inflation in housing prices. Well, one out of two ain’t bad.

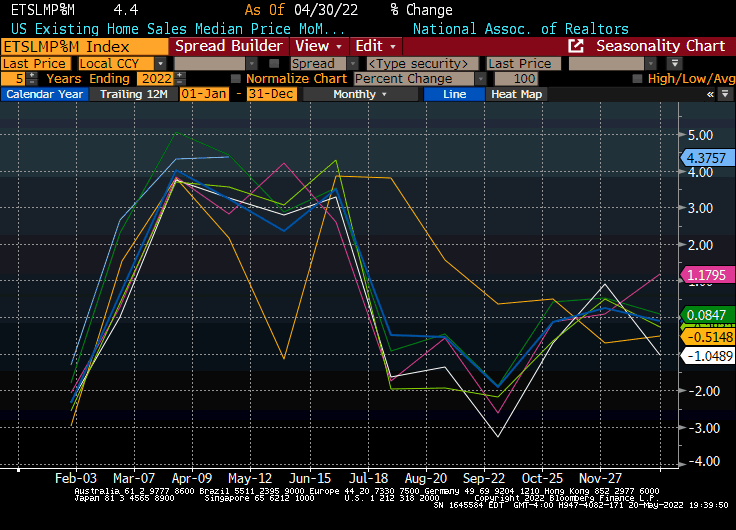

April’s increase in home prices was +4.38% month-over-month, keeping the y/y figure at +14.8%. Now, prices in the housing market are highly seasonal, but still: April 2005 and April 2013 were the only years this century when the m/m gains in April were higher. The first of those years was when when the housing bubble was inflating; the second was when they were bouncing after the bubble collapsed.

The following chart from Bloomberg shows the m/m changes, by calendar month, for the last 5 years. The thin blue line up top is the April m/m gain.

So, while home sales were weak, home price increases remain very strong. Surely, they cannot continue at 15-20% per year.

But the important point is that the connection between home sales and home prices is tenuous at best. In housing, there are at least two reasons for this, and one of them applies to markets in general. The first reason, to which I alluded last week, is that the first impact of higher mortgage rates is on the more price-sensitive buyers. But the bigger reason is that as long as the overall price level itself continues to increase rapidly, the nominal price of any fixed asset should keep increasing as well.

The price level is changing. A 14% y/y increase in home prices when inflation is at 8% is the same in real terms as an 8% increase when inflation is at 2%. We look at 14% and say “wow,” but that’s because we are looking with “2% inflation” eyes. Since 1999, median home prices have risen at an average rate of about 2.3% per year over the rate of inflation, including the boom and the bust in the 2000s. The current real rate of increase of 6%, while unsustainable in the long run, doesn’t seem completely outlandish to me. The thing to remember is that “2% inflation eyes” is the wrong frame to be using.

However, there’s no doubt that sales—which is in units, not dollars—are declining. The Fed is successfully slowing the economy. And if, in fact, Chairman Powell is true to his word and the Fed is going to keep pushing rates higher and risk a hard landing, then a landing we will get, good and hard. (I do remain skeptical that the Fed will be as cavalier if stocks keep declining and the unemployment rate starts to rise, but I also admit that I thought they’d concede in this game of economic chicken before now.)

Taking a Step Back…

Keep reminding yourself that the price level is changing and your “2% inflation eyes” will deceive you from time to time. As I’ve been pointing out in other contexts, even though “peak home price inflation” is probably behind us, that does not mean that home prices are due to decline.

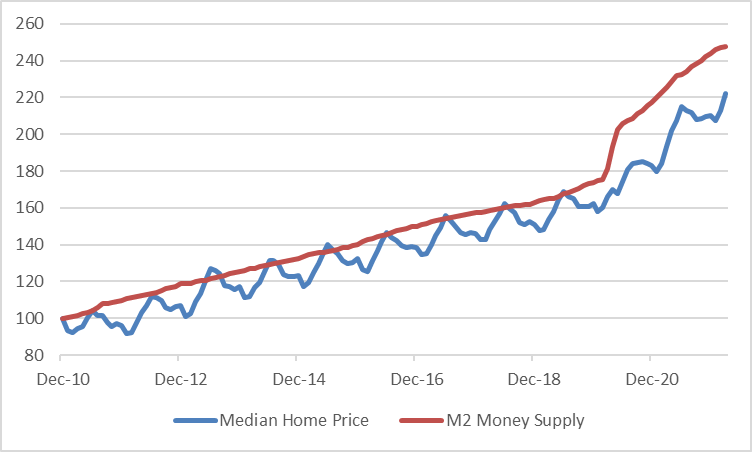

The currency is worth less now than it was before the crisis, because there is so much more of it. Since 2010, M2 has grown by 148%. Home prices have only grown by 122%.

The chart below (Source: National Association of Realtors, Federal Reserve; Enduring Investments calculations), indexed to the end of 2010, doesn’t seem to suggest that home prices are due to decline in nominal terms—and I measured the increase from near the bottom of the post-bubble trough.

The chart is also interesting because it seems to show a nice inflection in home prices right about the time we got a nice inflection in money supply growth. What a coincidence, right?

You could repeat this exercise for all sorts of assets and consumption items. What we are seeing in housing is a decline in unit sales but a continued rise in prices. In the economy, generally, we are starting to see a decline in unit sales growth—which is another way of saying real growth—but a continued rise in prices.

As we hear from companies on their conference calls talking about the change in sales, we hear them talking about two things. Dollar sales growth is the change in unit sales combined with the change in unit price. These are two different dials and they are affected by different things. It is entirely consistent, if the overall price level is rising, to see a decline in unit growth while the price per unit continues to rise. GDP is measured in real units.

In a nutshell, that is why we are very likely to get a contraction in real GDP (aka a recession) while still seeing inflation. Good job, Fed. As Geddy Lee once sang, sometimes the angels punish us by answering our prayers.

This is not to say that all prices will rise at the same rate, or that no prices will retrace some of the post-COVID spike. But it is very important to recognize the difference between changes in relative prices (some going up faster than overall inflation, and some slower) and changes in the absolute level of prices. Different product prices will ebb and flow. Those are waves. The price level itself is the tide. The tide is coming in. Move your castles higher on the sand.

Michael Ashton, sometimes known as The Inflation Guy, is the Managing Principal of Enduring Investments, LLC. He's a pioneer in inflation markets with a specialty in defending wealth against the assaults of economic inflation, which he discusses on his Cents and Sensibility podcast.