(Bloomberg Opinion) -- Business investment, generally speaking, is good. When companies buy things like new buildings, machines, software, vehicles or intangible assets, it helps the economy in at least four ways. First, those new capital goods require new workers to use them, so this investment tends to go along with hiring. Second, the companies that create the new capital goods get a boost. Third, having more long-lasting, productive capital goods like buildings, machines and vehicles increases a society’s overall productive power, raising wealth in the long run. And fourth, new capital goods often contain cutting-edge technology that increases productivity.

Governments use a variety of tools to push companies to invest more. Some of these tools are direct -- for example governments let companies write off investments on their taxes. Some are indirect incentives that focus on trying to encourage people to buy the stocks and bonds of companies, in the hope that the companies will use that money to boost investment. This is one reason capital gains and dividends are taxed at a lower rate than ordinary income. Governments may also try to encourage investment by lowering the rate of tax on corporate profits -- since capital goods are basically long-term profit-generating items, allowing companies to keep more of their profits makes capital goods more valuable.

The tax reform enacted by President Donald Trump and the Republican-controlled Congress in 2017 contained two main incentives. It cut the federal corporate tax rate substantially, from a top rate of 35 percent to a top rate of 21 percent. And it let companies expense their investments immediately, instead of piecemeal over a period of years, for the next five years. Theoretically, investment should rise as a result. On the other hand, the reform also switched the U.S. to a so-called worldwide tax system, which could encourage companies to ship operations overseas instead of investing at home.

The effect of the tax reform is really an empirical question. It’s possible that instead of buying new capital equipment, companies will respond to their tax cut windfall by returning the money to their investors, either with dividends or with share buybacks. Returning money to investors isn't a great sign, because it means that companies don’t have any good ideas for ways to deploy their money to generate long-term profits. It can also increase inequality. Investors might plow their dividends and capital gains back into the markets, where it may raise business investment eventually, or they can spend the money on yachts or mansions or whatever it is that rich people buy these days.

So which is actually happening? Only one quarter of data has been released since the tax cut was passed. In that time, business investment edged up to an all-time high:

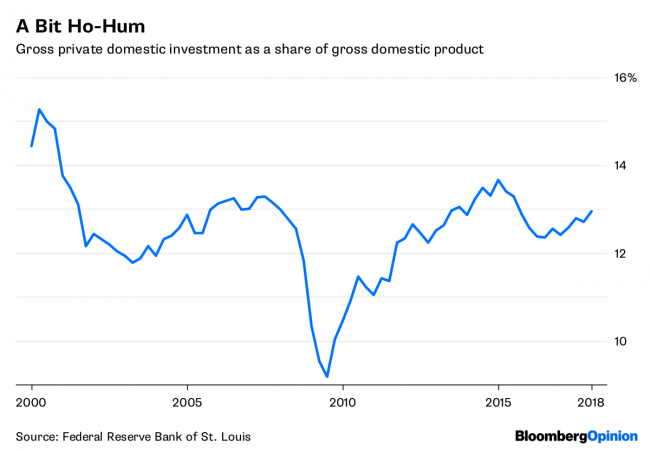

But as a percent of the economy, it’s not very large -- still below the post-recession peak set in 2015:

Theoretically, an investment-driven boom should make capital expenditure a larger piece of the economy.

Matt Phillips and Jim Tankersley, writing in the New York Times, were not impressed with the first quarter’s lukewarm investment growth. Paul Krugman, observing Apple’s plan to buy back $100 billion of stock, concluded that the tax cut was mainly a windfall for the rich.

Other accounts, however, are more optimistic. Bloomberg’s Lu Wang reported that capital expenditure is increasing faster than cash is being returned to investors:

Among the 130 companies in the S&P 500 that have reported results in this earnings season, capital spending increased by 39 percent, the fastest rate in seven years, data compiled by UBS AG show. Meanwhile, returns to shareholders are growing at a much slower pace, with net buybacks rising 16 percent. Dividends saw an 11 percent boost.

What accounts for the seeming discrepancy. The answer is that there has been a burst of capital expenditures, but it has been highly concentrated among a few large companies in a few industries. As for what’s happening with corporate America more broadly, it’s too early to tell.

“It’s too early to tell” probably should be the watchword on tax reform at this point. Even if we had perfect data on capital spending and buybacks for every business in the country, it would only be a few months’ worth of data. The impact of tax reform can only really be judged over a much longer period. After several years, economists will be able to conduct studies evaluating the tax cut’s impact, much as they now are studying the impact of past policy changes.

Having to wait is frustrating for people who want an instant (and often partisan) answer to the question of whether Trump’s tax reform was good or bad. But it’s the only rational way to evaluate the policy’s true effects. Measures like investment as a percentage of gross domestic product, as well as wages, will be crucial to knowing whether the tax reform really helped average Americans or flowed into the pockets of the rich. In the meantime, we know little more than we knew before the law was passed.