(Bloomberg) -- European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde is discovering that her grand ambitions for fighting climate change will have to take a back seat to her new job of reviving inflation.

Lagarde came to the Frankfurt-based ECB pledging to bind environmental concerns much more closely into policy decisions -- echoing her strategy when she ran the International Monetary Fund. Six weeks into the post, she’s refining her message after a clamor of warnings from colleagues such as Bundesbank President Jens Weidmann that their scope is limited by their mandate.

It means the Frenchwoman, who holds her first policy meeting on Thursday, now faces the risk of disappointing a chunk of the public at a time when climate issues are high on the global agenda. Her plans for a strategic review have built up expectations that the ECB will consider using its huge presence in debt markets to boost the growth of so-called green bonds that fund environmentally friendly projects.

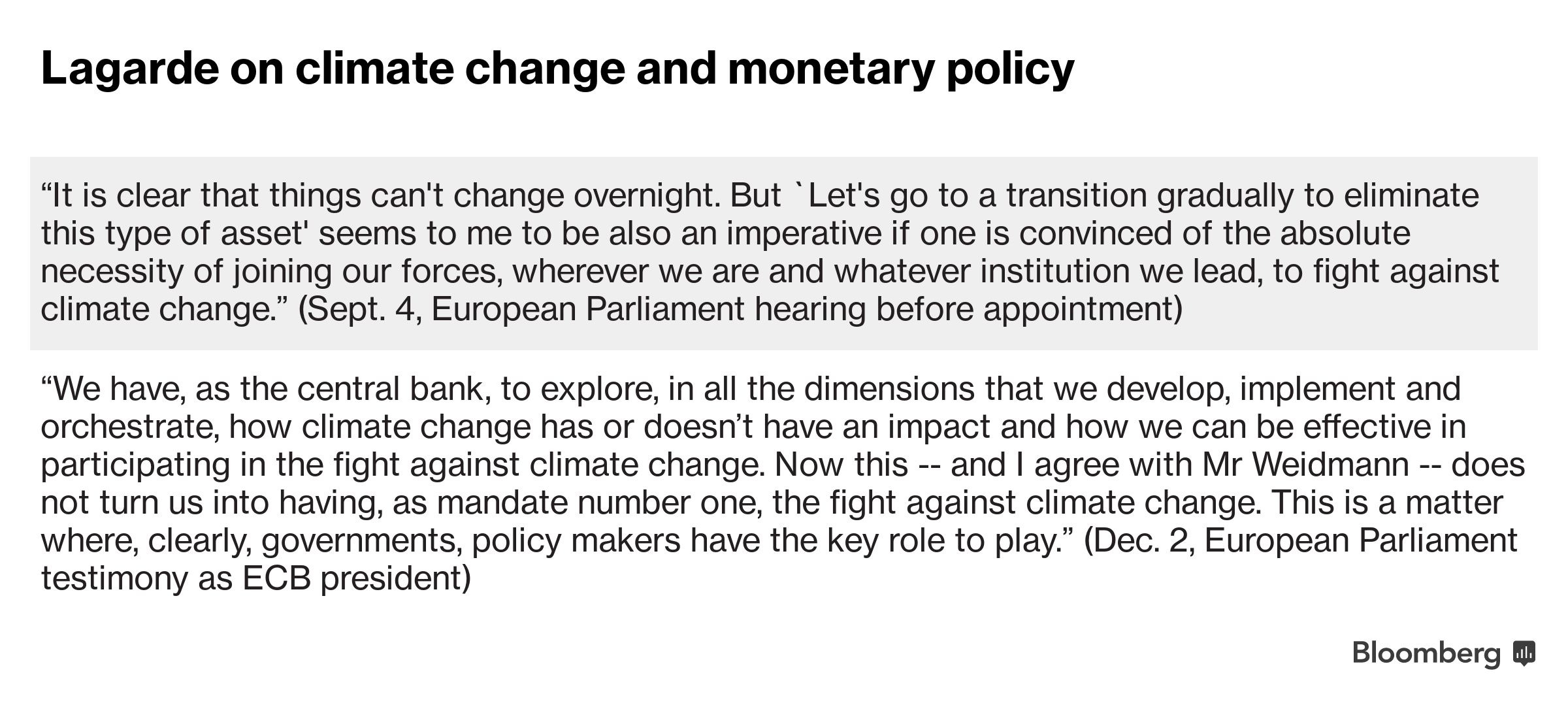

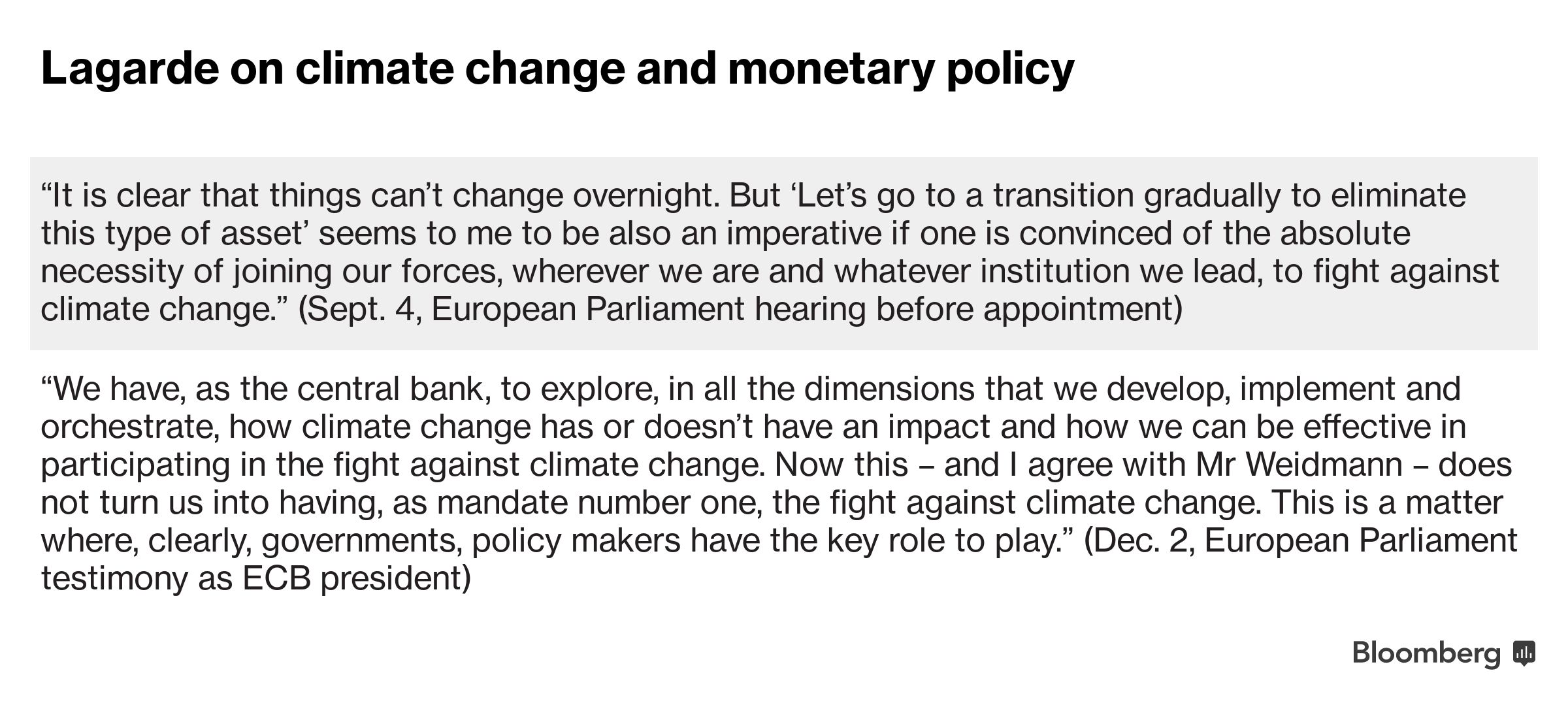

Lagarde’s thinking has emerged in her two recent appearances before the European Parliament. In September, for her confirmation hearing, she signaled that she was ready to make aggressive strides toward environmental objectives. Last week, in her first testimony as ECB chief, she appeared to pull back, saying the Governing Council -- which she heads -- will decide what to do, and fighting climate change is not its top priority.

“It’s not for the ECB or any other central bank to change its remit for something like climate change. That’s not to say that climate change isn’t humongously important,” said Tony Yates, a former adviser at the Bank of England. “If governments, on whose behalf central banks ultimately operate, if they can agree to anti-climate-change policies, which essentially are a set of taxes, then there’s no need for central banks to do anything.”

It’s clear that Lagarde has tapped into the zeitgeist. Before last week’s testimony in Brussels, she met with non-governmental organizations who delivered a letter pushing her to be proactive. Ester Asin, director of the WWF European policy office, said the ECB’s priority must be to “stop supporting carbon-intensive sectors like fossil fuels and dramatically increase its purchases of green bonds.”

One area where the president does seem to see room for maneuver is whether quantitative easing should remain market neutral. In both parliamentary sessions, she signaled that the ECB could adopt pending European standards defining sustainable investments -- what the European Commission calls a “taxonomy” -- that might help skew purchases away from carbon-intensive brown bonds to green ones.

That’s controversial for many policy makers though. The central bank has attached great importance to neutrality to avoid accusations of making judgments that are best left to elected governments. It means holding green bonds in proportion to the market as a whole -- a ratio most estimates put well below 5%.

Moreover, while officials agree that climate change will have a deep economic impact, they don’t want to muddy their more-pressing mission of reaching their inflation goal of just-under 2%. It’s something they’ve struggled with for years, and it’ll also be part of the review.

Weidmann dismissed the idea of greening QE in late October, Executive Board member Benoit Coeure said central banks must help fight climate change but can’t be at the forefront, and Dutch governor Klaas Knot said the battle mustn’t come at the expense of the focus on inflation. Officials from Austria to Italy have weighed in with similar sentiments, as has a former vice president.

The ECB isn’t ignoring global warming. As a member of the Network for Greening the Financial System, it’s contributing to the international debate about how central banks and supervisors can foster sustainable investment, setting standards that could serve as benchmark also for the private sector.

Under QE, it already holds more than half of non-financial bonds included in the Bloomberg Barclays (LON:BARC) euro green corporate bond index -- most of the rest is ineligible under the ECB’s rules. It also allows for purchases of larger portions of debt from organizations such as the European Investment Bank, one of the world’s largest providers of climate finance.

In her European parliament testimony, Lagarde identified three other areas where the ECB can and has taken action:

- Incorporating climate-change risks into the models it uses to predict the economic outlook

- Helping banks it supervises to properly evaluate threats and testing their resilience

- Favoring green assets in managing its pension portfolio

“Should it be revisited? Should we look at it? How do we do that? ” she said last week. “Those are questions on which I’m not passing judgment. I don’t have a final say.